Commercial Crew Program

[1] NASA has contracted for six operational missions from Boeing and fourteen from SpaceX, ensuring sufficient support for ISS through 2030.

Between the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011 and the first operational CCP mission in 2020, NASA relied on the Soyuz program to transport its astronauts to the ISS.

Instead of a splashdown, a Starliner capsule will return on land with airbags at one of four designated sites in the western United States.

A series of open competitions over the following two years saw successful bids from Boeing, Blue Origin, Sierra Nevada, and SpaceX to develop proposals for ISS crew transport vehicles.

In 2014, NASA awarded separate fixed-price contracts to Boeing and SpaceX to develop their respective systems and to fly astronauts to the ISS.

[13][15][16] This arrangement would additionally end NASA's dependency on Roscosmos' Soyuz program to deliver its astronauts to the ISS.

[17][18] The NASA Authorization Act of 2010 allocated US$1.3 billion for an expansion of the existing Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program over three years.

[35] In December 2012, the three CCiCap winners were each given an additional USD$10 million in funding as the first of two series of "certification products contracts" (CPC) to allow for further testing, engineering standards, and design analysis to meet NASA's safety requirements for crewed spaceflight.

[40][41] Sierra Nevada filed a protest with the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in response, citing "serious questions and inconsistencies in the source selection process.

[47][48] The company laid off 90 staff members working on the Dream Chaser following the CCtCap result, and repurposed the spacecraft as a for-hire vehicle for commercial spaceflight.

[58][59] With no further flights in the Soyuz program for American astronauts past 2018,[60] the GAO expressed concerns and recommended in February 2017 that NASA develop a plan for crew rotation in the event of further delays.

[70][71] The capsule used in the mission, however, was accidentally destroyed in a static fire test of its SuperDraco engines in April 2019,[72][73][74] causing further delays to launch of future Crew Dragon flights.

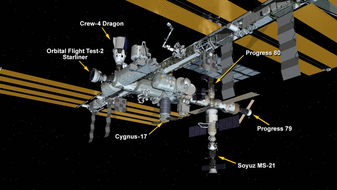

[83][84] Boeing conducted the Orbital Flight Test in December 2019 and encountered major malfunctions of Starliner's software which precluded an intended docking with the ISS and prompted a truncation of the mission.

When Boeing OFT-2 was on the pad preparing for launch on 3 August 2021, problems were encountered with 13 valves in the capsule's propulsion system.

[114] The IDSS docks are used instead of the Common Berthing Mechanism used by previous Commercial Orbital Transportation Services spacecraft such as the first-generation Dragon.

[126] Each Crew Dragon capsule is equipped with a launch escape system consisting of eight of SpaceX's SuperDraco engines, which provide 71,000 newtons (16,000 pounds-force) of thrust each.

[112] Unlike Crew Dragon, Starliner is designed to return to Earth on land instead of ocean, using airbags to cushion the vehicle's impact with the ground.

[144][145] Four sites in the western contiguous United States – the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, Edwards Air Force Base in California, White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, and Willcox Playa in Arizona – will serve as landing ranges for returning Starliner spacecraft,[145] though in an emergency scenario, it is also equipped to perform a splashdown return.

[147][148] NASA later contracted with SpaceX for up to an additional eight flights as a contingency if Starliner is further delayed and to ensure service to the ISS until 2030.

[2] SpaceX's Crew-1 mission, the first operational flight in the program, carried Victor Glover, Mike Hopkins, Soichi Noguchi, and Shannon Walker to the ISS in November 2020 aboard Resilience.

[153][156][157] The mission carried Shane Kimbrough, Megan McArthur, Akihiko Hoshide and Thomas Pesquet aboard Endeavour.

That would ensure both countries would have a presence on the station, and ability to maintain their separate systems, if either Soyuz or commercial crew vehicles are grounded for an extended period.

[168] On 3 December 2021, NASA made clear it would secure up to an additional three flights from SpaceX to maintain an uninterrupted U.S. capability for human access to the space station.

This arrangement ensures that ISS will have at least one crew member to operate essential services even if one or the other type of spacecraft is grounded.

Problems with the Starliner caused NASA to extend its mission and ultimately to bring the spacecraft back to Earth without crew.