Manorialism

An essential element of feudal society,[7][5] manorialism was slowly replaced by the advent of a money-based market economy and new forms of agrarian contract.

[12] The Laws of Constantine I around 325 both reinforced the semi-servile status of the coloni and limited their rights to sue in the courts; the Codex Theodosianus promulgated under Theodosius II extended these restrictions.

The legal status of adscripti, "bound to the soil",[13] contrasted with barbarian foederati, who were permitted to settle within the imperial boundaries, remaining subject to their own traditional law.

By extension, the word manor is sometimes used in England as a slang term for any home area or territory in which authority is held, often in a police or criminal context.

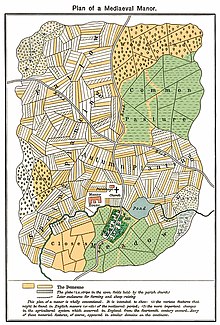

[14][15] In the generic plan of a medieval manor[16] from Shepherd's Historical Atlas,[17] the strips of individually worked land in the open field system are immediately apparent.

As concerns for privacy[dubious – discuss] increased in the 18th century,[citation needed] manor houses were often located a farther distance from the village.

He solved this problem by allotting "desert" tracts of uncultivated land belonging to the royal fisc under direct control of the emperor.

He can be an individual, in the vast majority of cases a national of the nobility or of the Bourgeoisie, but also a judicial person most often an ecclesiastical institution such as an abbey, a cathedral or canonical chapter or a military order.

[18] Manors each consisted of up to three classes of land: Additional sources of income for the lord included charges for use of his mill, bakery or wine-press, or for the right to hunt or to let pigs feed in his woodland, as well as court revenues and single payments on each change of tenant.

On the other side of the account, manorial administration involved significant expenses, perhaps a reason why smaller manors tended to rely less on villein tenure.

Villein land could not be abandoned, at least until demographic and economic circumstances made flight a viable proposition; nor could they be passed to a third party without the lord's permission, and the customary payment.

[20][21] In many settlements during the early modern period, illegal building was carried out on lord's waste land by squatters who would then plead their case to remain with local support.

[23] In examining the origins of the monastic cloister, Walter Horn found that "as a manorial entity the Carolingian monastery ... differed little from the fabric of a feudal estate, save that the corporate community of men for whose sustenance this organisation was maintained consisted of monks who served God in chant and spent much of their time in reading and writing.

In the later Middle Ages, areas of incomplete or non-existent manorialisation persisted while the manorial economy underwent substantial development with changing economic conditions.

This situation sometimes led to replacement by cash payments or their equivalents in kind of the demesne labour obligations of those peasants living furthest from the lord's estate.

[citation needed] The effect of circumstances on manorial economy is complex and at times contradictory: upland conditions tended to preserve peasant freedoms (livestock husbandry in particular being less labour-intensive and therefore less demanding of villein services); on the other hand, some upland areas of Europe showed some of the most oppressive manorial conditions, while lowland eastern England is credited with an exceptionally large free peasantry, in part a legacy of Scandinavian settlement.