Marcus Aurelius

[9] The main narrative source for the period is Cassius Dio, a Greek senator from Bithynian Nicaea who wrote a history of Rome from its founding to 229 in eighty books.

[10] Some other literary sources provide specific details: the writings of the physician Galen on the habits of the Antonine elite, the orations of Aelius Aristides on the temper of the times, and the constitutions preserved in the Digest and Codex Justinianeus on Marcus's legal work.

[24] Through his grandmother Rupilia Faustina, Marcus was related to the Nerva-Antonine dynasty; Rupilla was the step-daughter of Salonia Matidia, who was the niece of the emperor Trajan.

He trained in wrestling as a youth and into his teenage years, learned to fight in armour and joined the Salii, an order of priests dedicated to the god Mars that were responsible for the sacred shields, called Ancilia, and possibly for heralding war season's beginning and end.

Marcus was educated at home, in line with contemporary aristocratic trends;[48] he thanks Catilius Severus for encouraging him to avoid public schools.

[51] A new set of tutors – the Homeric scholar Alexander of Cotiaeum along with Trosius Aper and Tuticius Proculus, teachers of Latin[52][note 3] – took over Marcus's education in about 132 or 133.

Convalescent in his villa at Tivoli, he selected Lucius Ceionius Commodus, Marcus's intended father-in-law, as his successor and adopted son,[57] according to the biographer 'against the wishes of everyone'.

Nonetheless, his biographer attests that his character remained unaffected: 'He still showed the same respect to his relations as he had when he was an ordinary citizen, and he was as thrifty and careful of his possessions as he had been when he lived in a private household'.

Fronto exercised a complete mastery of Latin, capable of tracing expressions through the literature, producing obscure synonyms, and challenging minor improprieties in word choice.

As the grandson of Arulenus Rusticus, one of the martyrs to the tyranny of Domitian (r. 81–96), he was heir to the tradition of 'Stoic Opposition' to the 'bad emperors' of the 1st century;[126] the true successor of Seneca (as opposed to Fronto, the false one).

Contemporary coinage commemorates the event, with crossed cornucopiae beneath portrait busts of the two small boys, and the legend temporum felicitas, 'the happiness of the times'.

[134] He quoted from the Iliad what he called the "briefest and most familiar saying [...] enough to dispel sorrow and fear":[135] leaves, the wind scatters some on the face of the ground; like unto them are the children of men.

Lucius had a markedly different personality from Marcus: he enjoyed sports of all kinds, but especially hunting and wrestling; he took obvious pleasure in the circus games and gladiatorial fights.

[156] Although Marcus showed no personal affection for Hadrian (significantly, he does not thank him in the first book of his Meditations), he presumably believed it his duty to enact the man's succession plans.

Reflecting on the speech he had written on taking his consulship in 143, when he had praised the young Marcus, Fronto was ebullient: "There was then an outstanding natural ability in you; there is now perfected excellence.

'[224] Fronto sent Marcus a selection of reading material,[226] and, to settle his unease over the course of the Parthian war, a long and considered letter, full of historical references.

There had been reverses in Rome's past, Fronto writes,[227] but in the end, Romans had always prevailed over their enemies: 'Always and everywhere [Mars] has changed our troubles into successes and our terrors into triumphs'.

[241] Lucilla was accompanied by her mother Faustina and Lucius's uncle (his father's half-brother) M. Vettulenus Civica Barbarus,[242] who was made comes Augusti, 'companion of the emperors'.

The citizens of Seleucia, still largely Greek (the city had been commissioned and settled as a capital of the Seleucid Empire, one of Alexander the Great's successor kingdoms), opened its gates to the invaders.

Lucius Dasumius Tullius Tuscus, a distant relative of Hadrian, was in Upper Pannonia, succeeding the experienced Marcus Nonius Macrinus.

This was not a new thing, but this time the numbers of settlers required the creation of two new frontier provinces on the left shore of the Danube, Sarmatia and Marcomannia, including today's Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary.

[275] Like many emperors, Marcus spent most of his time addressing matters of law such as petitions and hearing disputes,[276] but unlike many of his predecessors, he was already proficient in imperial administration when he assumed power.

[280] Marcus showed a great deal of respect to the Roman Senate and routinely asked them for permission to spend money even though he did not need to do so as the absolute ruler of the Empire.

This may have been the port city of Kattigara, described by Ptolemy (c. 150) as being visited by a Greek sailor named Alexander and lying beyond the Golden Chersonese (i.e. Malay Peninsula).

Galen, who was in Rome when the plague spread to the city in 166,[289] mentioned that "fever, diarrhoea, and inflammation of the pharynx, along with dry or pustular eruptions of the skin after nine days" were among the symptoms.

[note 18] He was immediately deified and his ashes were returned to Rome, where they rested in Hadrian's mausoleum (modern Castel Sant'Angelo) until the Visigoth sack of the city in 410.

There are stray references in the ancient literature to the popularity of his precepts, and Julian the Apostate was well aware of his reputation as a philosopher, though he does not specifically mention Meditations.

[326] The historian Herodian wrote: Alone of the emperors, he gave proof of his learning not by mere words or knowledge of philosophical doctrines but by his blameless character and temperate way of life.

[327]Iain King explains that Marcus's legacy was tragic: [The emperor's] Stoic philosophy – which is about self-restraint, duty, and respect for others – was so abjectly abandoned by the imperial line he anointed on his death.

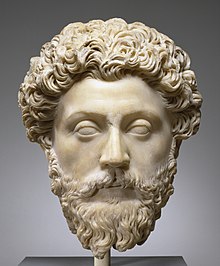

The emperor's hand is outstretched in an act of clemency offered to a bested enemy, while his weary facial expression due to the stress of leading Rome into nearly constant battles perhaps represents a break with the classical tradition of sculpture.