Margaret Cameron (author)

May Lamberton Becker, outlining in the New York Evening Post a course of study in American humor, mentioned Margaret Cameron as one of the three women humorists thus far produced by this country.

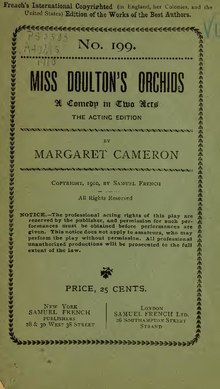

Cameron wrote several one-act plays for amateurs, all in a vein of light, satirical comedy; many short stories, summarized by one critic as “delicious bits of fooling, developed with an absurd solemnity that is captivating”; two books of travel in actionized form, one of which, The Involuntary Chaperon, was considered to be the first South American travel book published in the U.S.;[1] and a novel, Johndover, in which was presented a image of Santa Barbara, California during the last years of a romantic period.

Her father suffered from an illness contracted in the Civil War, and when Margaret was nine years old, the family moved from Illinois to Santa Barbara, California, hoping thereby to benefit his health.

It was the winter of 1876-1877, a "dry year", with a long succession of sunny days and no rain, when crops failed for lack of water and cattle died by thousands on the neighboring ranches from thirst and starvation.

At fourteen, she was admitted to a Shakespeare Club of otherwise middleaged and elderly persons, and because her dramatic sense was starved in isolated Santa Barbara, where the only theatrical entertainment was supplied at long intervals by cheap, itinerant companies, these Shakespearean readings were her greatest pleasure.

Among her older friends in Santa Barbara were persons of varied and cultivated tastes, inspiring her with a desire to share their interests, and each season brought a thin stream of tourists from the East, some of whom gave her glimpses of things to hope and work for.

[2] She was a gifted teacher and when, two years later, in Oakland, California, she began to teach pupils in the rudiments of music, her ability to impart what she knew, and a liking for doing it, increased her class and brought her an income sufficient for her small needs.

Cameron said it was a paper without much influence, but she wished to do well whatever she attempted, and realizing that she knew very little about vocal technique, she entered the studio of Francis Stuart to gain a knowledge of singing through hearing him teach, while she played accompaniments for his pupils.

[2] In 1898, Cameron stopped teaching music, though she continued her work as an accompanist for two or three years, and having been actively employed for a long time, she was unhappy without a definite occupation.

Very conscious of the limitations of her education, this impressed her as an opportunity to learn more than her scanty schooling had taught her about the technical side of literature, and with that object in view, she helped organize a class in Oakland and became one of the pupils.

[2] On September 16, 1903, she married Harrison Cass Lewis (1863-1926),[3] who was the General Manager and Vice-President of the National Paper & Type Company, exporting printer’s materials to Latin American countries.

[9] It was a clear, straight-forward report of actual occurrences, published somewhat reluctantly and only because the obligation of service, the necessity of sharing this experience with those whom it might help, outweighed with the writer any personal shrinking from possible ridicule.

Both her publishers and her public were surprised by this departure from her accustomed writing, but no one else was as profoundly astonished as she was herself by what she had to report, for she had no tendency toward mysticism and no inclination to speculate about things unseen.