Mexican Revolution

[12] The aging Díaz failed to find a controlled solution to presidential succession, resulting in a power struggle among competing elites and the middle classes, which occurred during a period of intense labor unrest, exemplified by the Cananea and Río Blanco strikes.

This initiated a new and bloody phase of the Revolution, as a coalition of northerners opposed to the counter-revolutionary regime of Huerta, the Constitutionalist Army led by the Governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza, entered the conflict.

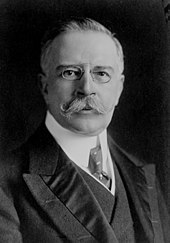

[20] In his early years in the presidency, Díaz consolidated power by playing opposing factions against each other and by expanding the Rurales, an armed police militia directly under his control that seized land from local peasants.

There was what one scholar has called "agrarian compression", in which "population growth intersected with land loss, declining wages and insecure tenancies to produce widespread economic deterioration", but the regions under the greatest stress were not the ones that rebelled.

"[45] In 1910, Francisco I. Madero, a young man from a wealthy landowning family in the northern state of Coahuila, announced his intent to challenge Díaz for the presidency in the next election, under the banner of the Anti-Reelectionist Party.

[54] He appeared to be a moderate, but the German ambassador to Mexico, Paul von Hintze, who associated with the Interim President, said of him that "De la Barra wants to accommodate himself with dignity to the inevitable advance of the ex-revolutionary influence, while accelerating the widespread collapse of the Madero party.

"[59] Ignoring the warning, Madero increasingly relied on the Federal Army as armed rebellions broke out in Mexico in 1911–12, with particularly threatening insurrections led by Emiliano Zapata in Morelos and Pascual Orozco in the north.

[60] The anarcho-syndicalist Casa del Obrero Mundial (House of the World Worker) was founded in September 1912 by Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, Manuel Sarabia, and Lázaro Gutiérrez de Lara and served as a center of agitation and propaganda, but it was not a formal labor union.

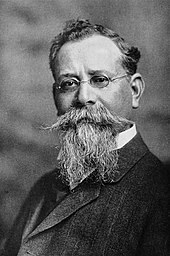

Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, who had done all he could to undermine U.S. confidence in Madero's presidency, brokered the Pact of the Embassy, which formalized the alliance between Félix Díaz and Huerta, with the backing of the United States.

Alvaro Obregón of Sonora, a successful rancher and businessman who had not participated in the Madero revolution, now joined the revolutionary forces in the north, the Constitutionalist Army under the Primer Jefe ("First Chief") Venustiano Carranza.

"[64] Huerta was even able to briefly muster the support of Andrés Molina Enríquez, author of The Great National Problems (Los grandes problemas nacionales), a key work urging land reform in Mexico.

Initially intended to prevent a German merchant vessel from delivering a shipment of arms to the Huerta regime, the muddled operation evolved into a seven-month stalemate resulting in the death of 193 Mexican soldiers, 19 U.S. servicemen and an unknown number of civilians.

The Federal Army's defeats caused Huerta's position to continue to deteriorate and in mid-July 1914, he stepped down and fled to the Gulf Coast port of Puerto México, seeking to get himself and his family out of Mexico rather than face the fate of Madero.

Obregón returned to Sonora and began building a power base that would launch his presidential campaign in 1919, which included the new labor organization headed by Luis N. Morones, the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers (CROM).

[138] "Obregón and the Sonorans, the architects of Carranza's rise and fall, shared his hard headed opportunism, but they displayed a better grasp of the mechanisms of popular mobilization, allied to social reform, that would form the bases of a durable revolutionary regime after 1920.

Many peasants also joined in opposition to the state's crackdown on religion, beginning the Cristero War, named for their clarion call Viva Cristo Rey ("long live Christ the king").

He vastly expanded agrarian reform, expropriated commercial landed estates; nationalized the railways and the petroleum industry; kept the peace with the Catholic Church as an institution; put down a major rebellion by Saturnino Cedillo; founded a new political party that created sectoral representation of industrial workers, peasants, urban office workers, and the army; engineered the succession of his hand-picked candidate; and then, perhaps the most radical act of all, stepped away from presidential power, letting his successor, General Manuel Ávila Camacho, exercise fully presidential power.

Seeing no opposition from the bourgeoisie, generals, or conservative landlords, in 1936 Cárdenas began building collective agricultural enterprises called ejidos to help give peasants access to land, mostly in southern Mexico.

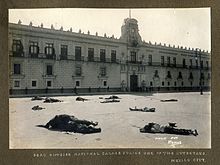

A notable exception is Mexico City, which only sustained damage during the days leading up to the ouster and murder of Madero, when rebels shelled the central core of the capital, causing the death of many civilians and animals.

[175] The alliance Carranza made with the Casa del Obrero Mundial helped fund that appealed to the urban working class, particularly in early 1915 before Obregón's victories over Villa and González's over Zapata.

[177] There were multiple newspapers written in the Spanish language, most notably, La Cronica, (The Chronicle in English) created by Nicasio Idar and his family in Laredo, Texas, a city which saw much action as a border town.

[177] These fronterizos would start out with two goals: to decry the racism and discrimination experienced by Mexicans and Mexicans-Americans in the United States, and to support the ongoing reforms in Mexico, equating the tyranny of Porfirio Díaz to that of white Texan politicians.

A month after the start of the conflict, Idar from La Cronica argued that Mexican immigrants and American born Mexican-Americans should be inspired by the revolution's promise of land reform to fight for more civil rights in the United States.

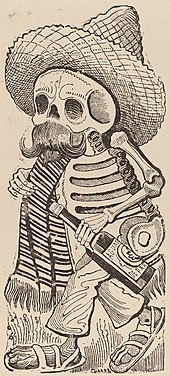

One published in El Vale Panchito entitled "oratory and music" shows Madero atop a pile of papers and the Plan of San Luis Potosí, haranguing a dark-skinned Mexican whose large sombrero has the label pueblo (people).

He was involved with the anarcho-syndicalist labor organization, the Casa del Obrero Mundial and in met and encouraged José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros in producing political art.

Often studied as an event solely of Mexican history, or one also involving Mexico's northern neighbor, scholars now recognize that "From the beginning to the end, foreign activities figured crucially in the Revolution's course, not simple antagonism from the U.S. government, but complicated Euro-American imperialist rivalries, extremely intricate during the first world war.

Díaz is still popularly and officially reviled, although there was an attempt to rehabilitate his reputation in the 1990s by President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who was implementing the North American Free Trade Agreement and amending the constitution to eliminate further land reform.

"[107] In the assessment of historian Alan Knight, "a victory of Villa and Zapata would probably have resulted in a weak, fragmented state, a collage of revolutionary fiefs of varied political hues presided over by a feeble central government.

Once in power, successive revolutionary generals holding the presidency, Obregón, Calles, and Cárdenas, systematically downsized the army and instituted reforms to create a professionalized force subordinate to civilian politicians.

[222] The army opened the sociopolitical system and the leaders in the Constitutionalist faction, particularly Álvaro Obregón and Plutarco Elías Calles, controlled the central government for more than a decade after the military phase ended in 1920.