Market failure

[13] Most mainstream economists believe that there are circumstances (like building codes, fire safety regulations or endangered species laws) in which it is possible for government or other organizations to improve the inefficient market outcome.

In some cases, monopolies can maintain themselves where there are "barriers to entry" that prevent other companies from effectively entering and competing in an industry or market.

It is hard to say who discovered externalities first since many classical economists saw the importance of education or a lighthouse, but it was Alfred Marshall who wanted to explore this more.

Coase used a few more examples similar in scope dealing with social cost of an externality and the possible resolutions.

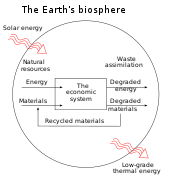

[3] Perhaps the best example of the inefficiency associated with common/public goods and externalities is the environmental harm caused by pollution and overexploitation of natural resources.

George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph E. Stiglitz developed the idea and shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics.

In another work, he states "boundedly rational agents experience limits in formulating and solving complex problems and in processing (receiving, storing, retrieving, transmitting) information" (Williamson, p. 553, citing Simon).

Simon describes a number of dimensions along which "classical" models of rationality can be made somewhat more realistic, while sticking within the vein of fairly rigorous formalization.

These include: Simon suggests that economic agents employ the use of heuristics to make decisions rather than a strict rigid rule of optimization.

A market is an institution in which individuals or firms exchange not just commodities, but the rights to use them in particular ways for particular amounts of time.

[31] Nonetheless, views still differ on whether something displaying these attributes is meaningful without the information provided by the market price system.

As an additional example of externalities, municipal governments enforce building codes and license tradesmen to mitigate the incentive to use cheaper (but more dangerous) construction practices, ensuring that the total cost of new construction includes the (otherwise external) cost of preventing future tragedies.

CITES is an international treaty to protect the world's common interest in preserving endangered species – a classic "public good" – against the private interests of poachers, developers and other market participants who might otherwise reap monetary benefits without bearing the known and unknown costs that extinction could create.

For example, the issue of systematic underinvestment in research is addressed by the patent system that creates artificial monopolies for successful inventions.

Beyond philosophical objections, a further issue is the practical difficulty that any single decision maker may face in trying to understand (and perhaps predict) the numerous interactions that occur between producers and consumers in any market.

Some advocates of laissez-faire capitalism, including many economists of the Austrian School, argue that there is no such phenomenon as "market failure".

Austrians argue that the market tends to eliminate its inefficiencies through the process of entrepreneurship driven by the profit motive; something the government has great difficulty detecting, or correcting.

[3] In addition, many Marxian economists would argue that the system of private property rights is a fundamental problem in itself, and that resources should be allocated in another way entirely.

Marxists, in contrast, would say that markets have inefficient and democratically unwanted outcomes – viewing market failure as an inherent feature of any capitalist economy – and typically omit it from discussion, preferring to ration finite goods not exclusively through a price mechanism, but based upon need as determined by society expressed through the community.

The fair and even allocation of non-renewable resources over time is a market failure issue of concern to ecological economics.

[39]: 156–160 This is an instance of a market failure passed unrecognized by most mainstream economists, as the concept of Pareto efficiency is entirely static (timeless).

[40]: 181f Imposing government restrictions on the general level of activity in the economy may be the only way of bringing about a more fair and even intergenerational allocation of the mineral stock.

[37]: 374–379 [40] However, Georgescu-Roegen, Daly, and other economists in the field agree that on a finite Earth, geologic limits will inevitably strain most fairness in the longer run, regardless of any present government restrictions: Any rate of extraction and use of the finite stock of non-renewable mineral resources will diminish the remaining stock left over for future generations to use.

Examples range from over-fishing of fisheries and over-grazing of pastures to over-crowding of recreational areas in congested cities.

It has been argued that the best way to remedy a 'tragedy of the commons'-type of ecological market failure is to establish enforceable property rights politically – only, this may be easier said than done.

[16]: 172f The issue of climate change presents an overwhelming example of a 'tragedy of the commons'-type of ecological market failure: The Earth's atmosphere may be regarded as a 'global common' exhibiting poorly defined (non-existing) property rights, and the waste absorption capacity of the atmosphere with regard to carbon dioxide is presently being heavily overloaded by a large volume of emissions from the world economy.

[45]: 347f Historically, the fossil fuel dependence of the Industrial Revolution has unintentionally thrown mankind out of ecological equilibrium with the rest of the Earth's biosphere (including the atmosphere), and the market has failed to correct the situation ever since.

Quite the opposite: The unrestricted market has been exacerbating this global state of ecological dis-equilibrium, and is expected to continue doing so well into the foreseeable future.