Marriage in Japan

The Heian period of Japanese history marked the culmination of its classical era, when the vast imperial court established itself and its culture in Heian-kyō (modern Kyoto).

Most members of the lower-class engaged in a permanent marriage with one partner, and husbands arranged to bring their wives into their own household, in order to ensure the legitimacy of their offspring.

[4] In the absence of sons, some households would adopt a male heir (養子, or yōshi) to maintain the dynasty, a practice which continues in corporate Japan.

Although Confucian ethics encouraged people to marry outside their own group, limiting the search to a local community remained the easiest way to ensure an honorable match.

The 17th century treatise Onna Daigaku ("Greater Learning for Women") instructed wives honor their parents-in-law before their own parents, and to be "courteous, humble, and conciliatory" towards their husbands.

Romantic love (愛情, aijō) played little part in medieval marriages, as emotional attachment was considered inconsistent with filial piety.

'floating world pictures') genre of woodblock prints celebrated the luxury and hedonism of the era, typically with depictions of beautiful courtesans and geisha of the pleasure districts.

Concubinage and prostitution were common, public, and relatively respectable, until the social upheaval of the Meiji Restoration put an end to feudal society in Japan.

[11] During the Meiji period, upper class and samurai customs of arranged marriage steadily replaced the unions of choice and mutual attraction that rural commoners had once enjoyed.

Public education became almost universal between 1872 and the early 1900s, and schools stressed the traditional concept of filial piety, first toward the nation, second toward the household, and last of all toward a person's own private interests.

The meeting was originally a samurai custom which became widespread during the early twentieth century, when commoners began to arrange marriages for their children through a go-between (仲人, nakoudo) or matchmaker.

A proposal by Baron Hozumi, who had studied abroad, that the absence of love be made a grounds for divorce failed to pass during debates on the Meiji Civil Code of 1898.

Chastity in marriage was expected for women, and a law not repealed until 1908 allowed a husband to kill his wife and her lover if he found them in an adulterous act.

The laws of the early Meiji period established several grounds on which a man could divorce: sterility, adultery, disobedience to parents-in-law, loquacity, larceny, jealousy, and disease.

[22] Omiai marriages, arranged by the parents or a matchmaker, remained the norm immediately after the war, although the decades which followed saw a steady rise in the number of ren'ai 'love matches'.

[26] Online dating services in Japan gained a reputation as platforms for soliciting sex, often from underage girls, for sexual harassment and assault, and for using decoy accounts (called otori or sakura in Japanese) to string along users in order to extend their subscriptions.

Newer services like Pairs, with 8 million users, or Omiai have introduced ID checks, age limits, strict moderation, and use of artificial intelligence to arrange matches for serious seekers.

[28]: 82 It reflects a professional class of matchmaking services which arrange meetings between potential partners, typically through social events, and often includes the exchange of resumes.

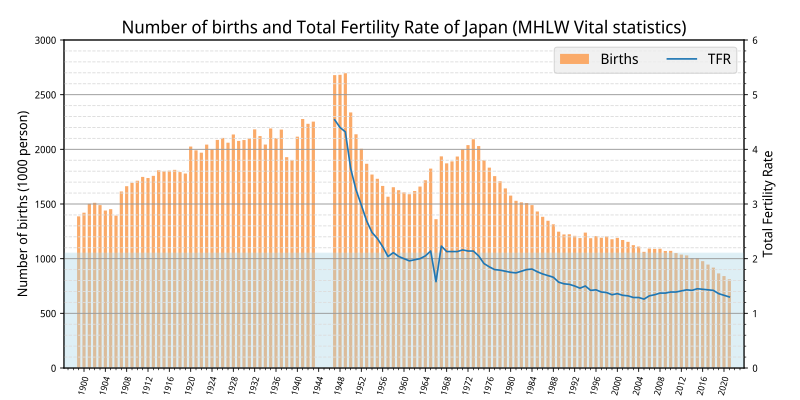

Economic factors, such as the cost of raising a child, work–family conflicts, and insufficient housing, are the most common reasons for young mothers (under 34) to have fewer children than desired.

[49] Recent media coverage has sensationalized surveys from the Japan Family Planning Association and the Cabinet Office that show a declining interest in dating and sexual relationships among young people, especially among men.

[34] The majority of Japanese people remain committed to traditional ideas of family, with a husband who provides financial support, a wife who works in the home, and two children.

[34][54][55] Labor practices, such as long working hours, health insurance, and the national pension system, are premised on a traditional breadwinner model.

As a result, Japan has largely maintained a gender-based division of labor with one of the largest gender pay gaps in the developed world, even as other countries began moving towards more equal arrangements in the 1970s.

[56] However, economic stagnation, anemic wage growth,[57] and job insecurity have made it more and more difficult for young Japanese couples to secure the income necessary to create a conventional family, despite their desire to do so.

[58][59][60] These non-regular employees earn about 53% less than regular ones on a comparable monthly basis, according to the Labor Ministry,[61] and as primary earners are seven times more likely to fall below the poverty line.

[32] Women postpone marriage for a variety of reasons, including high personal and financial expectations,[67] increasing independence afforded by education and employment,[68] and the difficulty of balancing work and family.

[69] Masahiro Yamada coined the term parasite singles (パラサイトシングル, parasaito shinguru) for unmarried adults in their late 20s and 30s who live with their parents, though it usually refers to women.

[75] According to the Ministry of Justice in 2010, 2,096 Russian, 404 Ukrainian, and 56 Belarussians were married to Japanese nationals, representing a minor share of cross-national marriages in Japan.

According to a summary of surveys by Japan's Gender Equality Bureau in 2006, 33.2% of wives and 17.4% of husbands have experienced either threats, physical violence, or rape, more than 10% of women repeatedly.

Japanese weddings usually begin with a Shinto or Western Christian-style ceremony for family members and very close friends before a reception dinner and after-party at a restaurant or hotel banquet hall.