Mary Dyer

"[5] The Dutch writer Gerard Croese wrote that she was reputed to be a "person of no mean extract and parentage, of an estate pretty plentiful, of a comely stature and countenance, of a piercing knowledge in many things, of a wonderful sweet and pleasant discourse, so fit for great affairs".

[6] Mary was married to William Dyer, a fishmonger and milliner, on 27 October 1633 at the parish church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, in Westminster, Middlesex, now a part of Central London.

As exploration of the North American continent was then leading to settlement, many Puritans opted to avoid state sanctions by emigrating to New England to practice their form of religion.

Instead of bringing peace, the sermon fanned the flames of controversy, and in Winthrop's words, Wheelwright "inveighed against all that walked in a covenant of works, ... and called them antichrists, and stirred up the people against them with much bitterness and vehemency.

[27][29] In his journal, Winthrop provided a more complete description as follows: it was of ordinary bigness; it had a face, but no head, and the ears stood upon the shoulders and were like an ape's; it had no forehead, but over the eyes four horns, hard and sharp; two of them were above one inch long, the other two shorter; the eyes standing out, and the mouth also; the nose hooked upward; all over the breast and back full of sharp pricks and scales, like a thornback [i.e., a skate or ray], the navel and all the belly, with the distinction of the sex, were where the back should be, and the back and hips before, where the belly should have been; behind, between the shoulders, it had two mouths, and in each of them a piece of red flesh sticking out; it had arms and legs as other children; but, instead of toes, it had on each foot three claws, like a young fowl, with sharp talons.

[31] Such microscopic inspection caused even private matters to become looked at publicly for the purpose of instruction, and Dyer's tragedy was widely examined for signs of God's judgment.

Winthrop felt that it was quite providential that the discovery of the "monstrous birth" occurred exactly when Anne Hutchinson was excommunicated from the local body of believers, and exactly one week before Dyer's husband was questioned in the Boston church for his heretic opinions.

[32] To further fuel Winthrop's beliefs, Anne Hutchinson suffered from a miscarriage later in the same year when she aborted a strange mass of tissue that appeared like a handful of transparent grapes (a rare condition, mostly in woman over 45, called a hydatidiform mole).

[34] In 1648 Samuel Rutherford, a Scottish Presbyterian, included Winthrop's account of the monster in his anti-sectarian treatise A Survey of the Spirituall Antichrist, Opening the Secrets of Familisme and Antinomianisme.

The New Englander, who used Winthrop's original description of the "monster" almost verbatim, has subsequently been identified as yet another well-known clergyman, John Eliot who preached at the church in Roxbury, not far from Boston.

[38] Scott's outlandish assertion was that the young Massachusetts governor, Henry Vane, fathered the "monstrous births" of both Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson; that he "debauched both, and both were delivered of monsters".

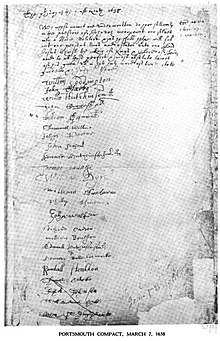

On 7 March 1638,[ambiguous] just as Anne Hutchinson's church trial was getting underway, a group of men gathered at the home of William Coddington and drafted a compact for a new government.

Within a year of the founding of this settlement, however, there was dissension among the leaders, and the Dyers joined Coddington, with several other inhabitants, in moving to the south end of the island, establishing the town of Newport.

Dyer's Newport neighbor, Herodias Gardiner who had made a perilous journey through a 60-mile wilderness to get to Weymouth in the Massachusetts colony was punished by being whipped ten times.

Dyer's husband had to come to Boston to get her out of jail, and he was bound and sworn not to allow her to lodge in any Massachusetts town, or to speak to any person while traversing the colony to return home.

Three other people who had also come to visit Holder and were then imprisoned were Nicholas Davis from Plymouth, the London merchant William Robinson and a Yorkshire farmer named Marmaduke Stephenson, the latter two on a Quaker mission from England.

[60] Davis returned to Plymouth, Dyer went home to Newport, but Robinson and Stephenson remained in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, spending time in Salem.

[59] When Dyer heard of these arrests, she once again left her home in Newport, and returned to Boston to support her Quaker brethren, ignoring her order of banishment, and once again being incarcerated.

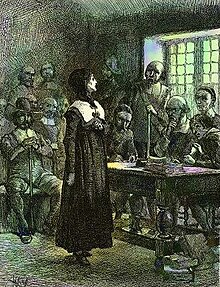

He then addressed the group, "We have made many laws and endeavored in several ways to keep you from among us, but neither whipping nor imprisonment, nor cutting off ears, nor banishment upon pain of death will keep you from among us.

Captain James Oliver of the Boston military company was directed to provide a force of armed soldiers to escort the prisoners to the place of execution.

Dyer's arms and legs were bound and her face was covered with a handkerchief provided by Reverend John Wilson who had been one of her pastors in the Boston church many years earlier.

[73] The Massachusetts General Court sent this document to the newly restored king in England, and in answer to it, the Quaker historian, Edward Burrough wrote a short book in 1661.

[77] She was determined to return to Boston to force the authorities to either change their laws or to hang a woman, and she left Shelter Island in April 1660 focused on this mission.

Johan Winsser presents evidence that Mary was buried on the Dyer family farm, located north of Newport where the Navy base is now situated in the current town of Middletown.

The strongest evidence found is the 1839 journal entry given by Daniel Wheeler, who wrote, "Before reaching Providence [coming from Newport], the site of the dwelling, and burying place of Mary Dyer was shown me.

"[86] Winsser provides other items of evidence lending credence to this notion; it is unlikely that Dyer's remains would have been left in Boston since she had a husband, many children, and friends living in Newport, Rhode Island.

[91] While news of Dyer's hanging was quick to spread through the American colonies and England, there was no immediate response from London because of the political turbulence, resulting in the restoration of the king to power in 1660.

[89][94] According to literary scholar Anne Myles, the life of Mary Dyer "functions as a powerful, almost allegorical example of a woman returning, over and over, to the same power-infused site of legal and discursive control".

The first is that Dyer's actions "can be read as staging a public drama of agency", a means for women, including female prophets, to act under the power and will of God.

[99] According to Myles, Dyer's life journey during her time in New England transformed her from "a silenced object to a speaking subject; from an Antinomian monster to a Quaker martyr".