Mass driver

A small mass driver could act as a rocket engine on board a spacecraft, flinging pieces of material into space to propel itself.

[2] Mass drivers need no physical contact between moving parts because they guide their projectiles by dynamic magnetic levitation, allowing extreme reusability in the case of solid-state power switching, and a functional life of – theoretically – up to millions of launches.

For instance, while Gerard O'Neill built his first mass driver in 1976–1977 with a $2000 budget, a short test model firing a projectile at 40 m/s and 33 g,[3] his next model had an order-of-magnitude greater acceleration[4] after a comparable increase in funding, and, a few years later, researchers at the University of Texas estimated that a mass driver firing a 10 kilogram projectile at 6000 m/s would cost $47 million.

[5][need quotation to verify][6][failed verification] For a given amount of energy involved, heavier objects go proportionally slower.

Due to the massive turbulence such launches would cause, significant air traffic control measures would be needed to ensure the safety of other aircraft operating in the area.

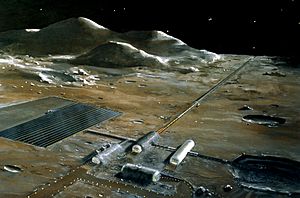

Based on this mode, a major proposal for the use of mass drivers involved transporting lunar-surface material to space habitats for processing using solar energy.

Alternatively, if a track were constructed along the entire circumference of the Moon (or any other celestial body without a significant atmosphere) then a reusable bucket's acceleration would not be limited by the length of the track – however, such a system would need to be engineered to withstand substantial centrifugal forces if it were intended to accelerate passengers and/or cargo to very high velocities.

In contrast to cargo-only chemical space-gun concepts, a mass driver could be any length, affordable, and with relatively smooth acceleration throughout, optionally even lengthy enough to reach target velocity without excessive g forces for passengers.

[11] By being mainly located slightly above, on or beneath the ground, a mass driver may be easier to maintain compared with many other structures of non-rocket spacelaunch.

[16] For rugged objects, much higher accelerations may suffice, allowing a far shorter track, potentially circular or helical (spiral).

With a suitable source of electrical power (probably a nuclear reactor) the spaceship could then use the mass driver to accelerate pieces of matter of almost any sort, boosting itself in the opposite direction.

However, practical engineering constraints apply for such as the power-to-mass ratio, waste heat dissipation, and the energy intake able to be supplied and handled.

Although the specific impulse of an electric thruster itself optionally could range up to where mass drivers merge into particle accelerators with fractional-lightspeed exhaust velocity for tiny particles, trying to use extreme exhaust velocity to accelerate a far slower spacecraft could be suboptimally low thrust when the energy available from a spacecraft's reactor or power source is limited (a lesser analogue of feeding onboard power to a row of spotlights, photons being an example of an extremely low momentum to energy ratio).

[19] For instance, if limited onboard power fed to its engine was the dominant limitation on how much payload a hypothetical spacecraft could shuttle (such as if intrinsic propellant economic cost was minor from usage of extraterrestrial soil or ice), ideal exhaust velocity would rather be around 62.75% of total mission delta v if operating at constant specific impulse, except greater optimization could come from varying exhaust velocity during the mission profile (as possible with some thruster types, including mass drivers and variable specific impulse magnetoplasma rockets).

[20][21][22][23] Another theoretical use for this concept of propulsion can be found in space fountains, a system in which a continuous stream of pellets in a circular track holds up a tall structure.

Small to moderate size high-acceleration electromagnetic projectile launchers are currently undergoing active research by the US Navy[24] for use as ground-based or ship-based weapons (most often railguns but coilguns in some cases).

On larger scale than weapons currently near deployment but sometimes suggested in long-range future projections, a sufficiently high velocity linear motor, a mass driver, could in theory be used as intercontinental artillery (or, if built on the Moon or in orbit, used to attack a location on Earth's surface).

[25][26][27] As the mass driver would be located further up the gravity well than the theoretical targets, it would enjoy a significant energy imbalance in terms of counter-attack.