Heterochromatin

Recent studies with electron microscopy and OsO4 staining reveal that the dense packing is not due to the chromatin.

It is usually repetitive and forms structural functions such as centromeres or telomeres, in addition to acting as an attractor for other gene-expression or repression signals.

Facultative heterochromatin is the result of genes that are silenced through a mechanism such as histone deacetylation or Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA) through RNAi.

However, under specific developmental or environmental signaling cues, it can lose its condensed structure and become transcriptionally active.

Heterochromatin mainly consists of genetically inactive satellite sequences,[11] and many genes are repressed to various extents, although some cannot be expressed in euchromatin at all.

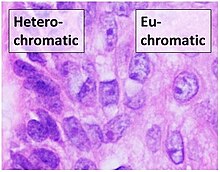

Some regions of chromatin are very densely packed with fibers that display a condition comparable to that of the chromosome at mitosis.

Among the molecular components that appear to regulate the spreading of heterochromatin are the Polycomb-group proteins and non-coding genes such as Xist.

[19] The polycomb repressive complexes PRC1 and PRC2 regulate chromatin compaction and gene expression and have a fundamental role in developmental processes.

RNA polymerase II synthesizes a transcript that serves as a platform to recruit RITS, RDRC and possibly other complexes required for heterochromatin assembly.

[23] A large RNA structure called RevCen has also been implicated in the production of siRNAs to mediate heterochromatin formation in some fission yeast.