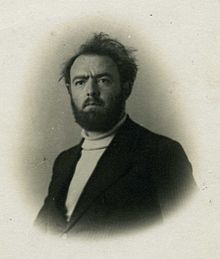

Matthijs Vermeulen

Matthijs Vermeulen (born Matheas Christianus Franciscus van der Meulen) (8 February 1888 – 26 July 1967), was a Dutch composer and music journalist.

In 1909 Vermeulen began to write for the Catholic daily newspaper De Tijd, where he soon distinguished himself by a personal, resolute tone which stood out in stark contrast to the usually long-winded music journalism of the day.

There Vermeulen revealed himself as an advocate of the music of Claude Debussy, Gustav Mahler and Alphons Diepenbrock, whom he later used to call his "maître spirituel".

In the reviews for 'De Telegraaf', a daily newspaper he worked for since 1915 as head of the Art and Literature department, he also showed just how much in his view politics and culture were inseparable.

Yet, Vermeulen started to work on his Second Symphony, Prélude à la nouvelle journée, shortly after that, and a year later he gave up journalism in order to fully dedicate himself to composing, while financially backed by some friends.

Seeking the meaning of this loss, Vermeulen drew up a philosophical construction, which he further developed in his book Het avontuur van den geest [The adventure of the mind].

The performance of the Second Symphony (which was awarded a prize at the 1953 Queen Elisabeth Music Competition in Brussels) during the 1956 Holland Festival instigated a new period of creativity.

Vermeulen moved to rural Laren with his wife and child, where he composed the Sixth Symphony Les minutes heureuses, followed by various songs and the String Quartet.

His last work, the Seventh Symphony, carrying the title Dithyrambes pour les temps à venir, reveals unflagging optimism.

A part of the audience thought that the socialist leader Troelstra, who had attempted a revolution days earlier, was meant and therefore interpreted Vermeulen's words as incitement, leading to great turmoil and a flurry of publications.

As a consequence, Vermeulen's Second Symphony, written 1919–20 and entitled Prelude à la nouvelle journée, had to wait until the 1950s for its premiere; Mengelberg publicly stated that he would not even look at it (though see also this link [1]).

As a result of numerous conflicts, Vermeulen decided to settle and work abroad for many years, particularly in France where he became a Paris correspondent for a journal in the then Dutch East Indies (Indonesia).

Although Vermeulen's writings on music give the impression that he was completely consistent in applying his polymelodic concept from the beginning until the end of a piece, most of his compositions contain several passages with only one or two voices, embedded in marvellous harmonies.

As opposed to Arnold Schoenberg, Vermeulen did not choose to build a new regulatory system, but proceeded purely in terms of thematic information and its logical and psychological development.

The Fourth Symphony is built on six themes, three of which return just before the end; the long epilogue is counterbalanced by the hammering prologue, both on the pedal tone C. The large-scale Violin Sonata is based on the major seventh, omnipresent both in melody and harmony.

These ambitions, put into words in the book titled Princiepen der Europese muziek (Principles of European music) and numerous articles, were at right angles to the mainstream movements.

Vermeulen's work has been quoted as seminal by influential Dutch composers such as Louis Andriessen, but his direct influence is much more difficult to trace - his style, after all, is eclectic and highly personal.