Maximum power transfer theorem

In electrical engineering, the maximum power transfer theorem states that, to obtain maximum external power from a power source with internal resistance, the resistance of the load must equal the resistance of the source as viewed from its output terminals.

If the load resistance is made larger than the source resistance, then efficiency increases (since a higher percentage of the source power is transferred to the load), but the magnitude of the load power decreases (since the total circuit resistance increases).

[2] If the load resistance is made smaller than the source resistance, then efficiency decreases (since most of the power ends up being dissipated in the source).

Although the total power dissipated increases (due to a lower total resistance), the amount dissipated in the load decreases.

It is a common misconception to apply the theorem in the opposite scenario.

The theorem can be extended to alternating current circuits that include reactance, and states that maximum power transfer occurs when the load impedance is equal to the complex conjugate of the source impedance.

The mathematics of the theorem also applies to other physical interactions, such as:[2][3] The theorem was originally misunderstood (notably by Joule[4]) to imply that a system consisting of an electric motor driven by a battery could not be more than 50% efficient, since the power dissipated as heat in the battery would always be equal to the power delivered to the motor when the impedances were matched.

In 1880 this assumption was shown to be false by either Edison or his colleague Francis Robbins Upton, who realized that maximum efficiency was not the same as maximum power transfer.

To achieve maximum efficiency, the resistance of the source (whether a battery or a dynamo) could be (or should be) made as close to zero as possible.

Using this new understanding, they obtained an efficiency of about 90%, and proved that the electric motor was a practical alternative to the heat engine.The efficiency η is the ratio of the power dissipated by the load resistance RL to the total power dissipated by the circuit (which includes the voltage source's resistance of RS as well as RL):

Consider three particular cases (note that voltage sources must have some resistance): A related concept is reflectionless impedance matching.

In radio frequency transmission lines, and other electronics, there is often a requirement to match the source impedance (at the transmitter) to the load impedance (such as an antenna) to avoid reflections in the transmission line.

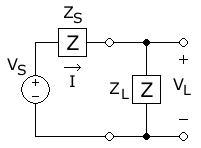

In the simplified model of powering a load with resistance RL by a source with voltage V and source resistance RS, then by Ohm's law the resulting current I is simply the source voltage divided by the total circuit resistance:

The power PL dissipated in the load is the square of the current multiplied by the resistance:

To find out whether this solution is a minimum or a maximum, the denominator expression is differentiated again:

When the source resistance can be varied, power transferred to the load can be increased by reducing

Note that this shows that maximum power transfer can also be interpreted as the load voltage being equal to one-half of the Thevenin voltage equivalent of the source.

[5] The power transfer theorem also applies when the source and/or load are not purely resistive.

A refinement of the maximum power theorem says that any reactive components of source and load should be of equal magnitude but opposite sign.

Physically realizable sources and loads are not usually purely resistive, having some inductive or capacitive components, and so practical applications of this theorem, under the name of complex conjugate impedance matching, do, in fact, exist.

If the source is totally inductive (capacitive), then a totally capacitive (inductive) load, in the absence of resistive losses, would receive 100% of the energy from the source but send it back after a quarter cycle.

Power factor correction (where an inductive reactance is used to "balance out" a capacitive one), is essentially the same idea as complex conjugate impedance matching although it is done for entirely different reasons.

For a fixed reactive source, the maximum power theorem maximizes the real power (P) delivered to the load by complex conjugate matching the load to the source.

In this diagram, AC power is being transferred from the source, with phasor magnitude of voltage

(positive peak voltage) and fixed source impedance

dissipated in the load is the square of the current multiplied by the resistive portion (the real part)

denote the reactances, that is the imaginary parts, of respectively the source and load impedances

for which this expression for the power yields a maximum, one first finds, for each fixed positive value of

This problem has the same form as in the purely resistive case, and the maximizing condition therefore is

The two maximizing conditions: describe the complex conjugate of the source impedance, denoted by