Medicinal plants

Plants synthesize hundreds of chemical compounds for various functions, including defense and protection against insects, fungi, diseases, against parasites[2] and herbivorous mammals.

[3] The earliest historical records of herbs are found from the Sumerian civilization, where hundreds of medicinal plants including opium are listed on clay tablets, c. 3000 BC.

The annual global export value of the thousands of types of plants with medicinal properties was estimated to be US$60 billion per year and growing at the rate of 6% per annum.

[citation needed] In many countries, there is little regulation of traditional medicine, but the World Health Organization coordinates a network to encourage safe and rational use.

The botanical herbal market has been criticized for being poorly regulated and containing placebo and pseudoscience products with no scientific research to support their medical claims.

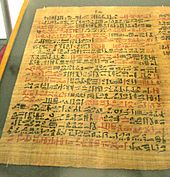

The ancient Egyptian Ebers Papyrus lists over 800 plant medicines such as aloe, cannabis, castor bean, garlic, juniper, and mandrake.

[16][17] In antiquity, various cultures across Europe, including the Romans, Celts, and Nordic peoples, also practiced herbal medicine as a significant component of their healing traditions.

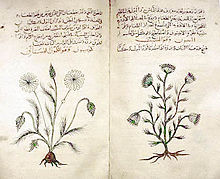

Notable works include those of Pedanius Dioscorides, whose "De Materia Medica" served as a comprehensive guide to medicinal plants and remained influential for centuries.

[18] Additionally, Pliny the Elder's "Naturalis Historia" contains valuable insights into Roman medical plant practices [19] Among the Celtic peoples of ancient Europe, herbalism played a vital role in both medicine and spirituality.

[22] The Chinese pharmacopoeia, the Shennong Ben Cao Jing records plant medicines such as chaulmoogra for leprosy, ephedra, and hemp.

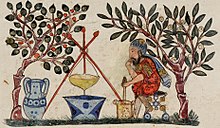

[5] During the Middle Ages, herbalism continued to flourish across Europe, with distinct traditions emerging in various regions, often influenced by cultural, religious, indigenous, and geographical factors.

In the Early Middle Ages, Benedictine monasteries preserved medical knowledge in Europe, translating and copying classical texts and maintaining herb gardens.

[28] In France, herbalism thrived alongside the practice of medieval medicine, which combined elements of Ancient Greek and Roman traditions.

[30] In the Iberian Peninsula, the regions of the North remained independent during the period of Islamic occupation, and retained their traditional and indigenous medical practices.

The Galician people were known for their strong connection to the land and nature and preserved botanical knowledge, with healers, known as "curandeiros" or "meigas," who relied on local plants for healing purposes [31] The Asturian landscape, characterized by lush forests and mountainous terrain, provided a rich source of medicinal herbs used in traditional healing practices, with "yerbatos," who possessed extensive knowledge of local plants and their medicinal properties [32] Barcelona, located in the Catalonia region of northeastern Spain, was a hub of cultural exchange during the Middle Ages, fostering the preservation and dissemination of medical knowledge.

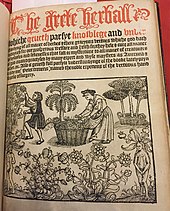

John Gerard wrote his famous The Herball or General History of Plants in 1597, based on Rembert Dodoens, and Nicholas Culpeper published his The English Physician Enlarged.

[41] Many new plant medicines arrived in Europe as products of Early Modern exploration and the resulting Columbian Exchange, in which livestock, crops and technologies were transferred between the Old World and the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Alkaloids were isolated from a succession of medicinal plants, starting with morphine from the poppy in 1806, and soon followed by ipecacuanha and strychnos in 1817, quinine from the cinchona tree, and then many others.

Medicines of different classes include atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine (all from nightshade),[68] the traditional medicine berberine (from plants such as Berberis and Mahonia),[b] caffeine (Coffea), cocaine (Coca), ephedrine (Ephedra), morphine (opium poppy), nicotine (tobacco),[c] reserpine (Rauvolfia serpentina), quinidine and quinine (Cinchona), vincamine (Vinca minor), and vincristine (Catharanthus roseus).

[83] Many polyphenolic extracts, such as from grape seeds, olives or maritime pine bark, are sold as dietary supplements and cosmetics without proof or legal health claims for medicinal effects.

[94] Traditional poultices were made by boiling medicinal plants, wrapping them in a cloth, and applying the resulting parcel externally to the affected part of the body.

[105] A 2012 phylogenetic study built a family tree down to genus level using 20,000 species to compare the medicinal plants of three regions, Nepal, New Zealand and the Cape of South Africa.

It discovered that the species used traditionally to treat the same types of condition belonged to the same groups of plants in all three regions, giving a "strong phylogenetic signal".

[98] In India, where Ayurveda has been practised for centuries, herbal remedies are the responsibility of a government department, AYUSH, under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare.

WHO has set out a strategy for traditional medicines[109] with four objectives: to integrate them as policy into national healthcare systems; to provide knowledge and guidance on their safety, efficacy, and quality; to increase their availability and affordability; and to promote their rational, therapeutically sound usage.

[109]The pharmaceutical industry has roots in the apothecary shops of Europe in the 1800s, where pharmacists provided local traditional medicines to customers, which included extracts like morphine, quinine, and strychnine.

[113] Some important phytochemicals, including curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate, genistein and resveratrol are pan-assay interference compounds, meaning that in vitro studies of their activity often provide unreliable data.

[117] Plant medicines can cause adverse effects and even death, whether by side-effects of their active substances, by adulteration or contamination, by overdose, or by inappropriate prescription.

[6] Herbal medicine and dietary supplement products have been criticized as not having sufficient standards or scientific evidence to confirm their contents, safety, and presumed efficacy.

[127][128][129][130] Companies often make false claims about their herbal products promising health benefits that aren't backed by evidence to generate more sales.