Tournament (medieval)

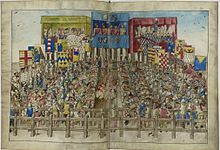

A tournament, or tourney (from Old French torneiement, tornei), was a chivalrous competition or mock fight that was common in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (12th to 16th centuries), and is a type of hastilude.

[1] But the shows were popular and often put on in honor of coronations, marriages, or births; to celebrate recent conquests or peace treatises; or to welcome ambassadors, lords, or others considered to be of great importance.

By the end of the 12th century, tornement and Latinized torneamentum had become the generic term for all kinds of knightly hastiludes or martial displays.

Roger of Hoveden writing in the late 12th century defined torneamentum as "military exercises carried out, not in the knight's spirit of hostility (nullo interveniente odio), but solely for practice and the display of prowess (pro solo exercitio, atque ostentatione virium).

[4] There may be an element of continuity connecting the medieval tournament to the hippika gymnasia of the Roman cavalry, but due to the sparsity of written records during the 5th to 8th centuries this is difficult to establish.

It is recognized by several medieval historical sources: a chronicler of Tours in the late 12th century attributes the "invention" of the knightly tournament to an Angevin baron, Geoffroi de Preulli, who supposedly died in 1066.

In 16th-century German historiography, the setting down of the first tournament laws is attributed to Henry the Fowler (r. 919–936); this tradition is cited by Georg Rüxner in his Thurnierbuch of c. 1530 as well as by Paulus Hector Mair in his De Arte Athletica (c.

[5] The earliest known use of the word "tournament" comes from peace legislation by Count Baldwin III of Hainaut for the town of Valenciennes, dated to 1114.

[6] The standard form of a tournament is evident in sources as early as the 1160s and 1170s, notably The History of William Marshal and the Arthurian romances of Chrétien de Troyes.

[7][citation needed] Tournaments might be held at all times of the year except the penitential season of Lent (the forty days preceding the Triduum of Easter).

Parties hosted by the principal magnates present were held in both settlements, and preliminary jousts (called the vespers or premières commençailles) offered knights an individual showcase for their talents.

There is evidence that squires were present at the lists (the staked and embanked line in front of the stands) to offer their masters up to three replacement lances.

The mêlée would tend then to degenerate into running battles between parties of knights seeking to take ransoms, and would spread over several square miles between the two settlements which defined the tournament area.

A few ended earlier, if one side broke in the charge, panicked and ran for its home base looking to get behind its lists and the shelter of the armed infantry which protected them.

Following a successful maneuver of this kind, the rank would attempt to turn around without breaking formation (widerkere or tornei); this action was so central that it would become eponymous of the entire tradition of the tourney or tournament by the mid-12th century.

The modern French form mêlée was borrowed into English in the 17th century and is not the historical term used for tournament mock battles.

Count Philip of Flanders made a practice in the 1160s of turning up armed with his retinue to the preliminary jousts, and then declining to join the mêlée until the knights were exhausted and ransoms could be swept up.

[15] The great tournaments of northern France attracted many hundreds of knights from Germany, England, Scotland, Occitania, and Iberia.

There is evidence that 3000 knights attended the tournament at Lagny-sur-Marne in November 1179 promoted by Louis VII in honour of his son's coronation.

The contemporary works of Bertran de Born talk of a tourneying world that also embraced northern Iberia, Scotland and the Empire.

In 1130, Pope Innocent II at a church council at Clermont denounced the tournament and forbade Christian burial for those killed in them.

Tournaments were allowed in England once again after 1192, when Richard I identified six sites where they would be permitted and gave a scale of fees by which patrons could pay for a license.

But both King John and his son, Henry III, introduced fitful and capricious prohibitions which much annoyed the aristocracy and eroded the popularity of the events.

In one of the last true tournaments held in England (in 1342 at Dunstable), the mêlée was postponed so long by jousting that the sun was sinking by the time the lines charged.

In the same year at a tournament at Cheapside, the king and other participants dressed as Tartars and led the ladies, who were in the colors of Saint George, in a procession at the start of the event.

[20] Edward III's grandson, Richard II (r. 1377–1399), would first distribute his livery badges with the White Hart at a tournament at Smithfield.

For a tournament honoring his marriage to Clarice Orsini in 1469, Lorenzo de' Medici had his standard designed by Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea del Verrocchio.

[25] In 1559, King Henry II of France died during a tournament when a sliver from the shattered lance of Gabriel Montgomery, captain of the Scottish Guard at the French Court, pierced his eye and entered his brain.