Memphis, Egypt

Memphis (Arabic: مَنْف, romanized: Manf, pronounced [mænf]; Bohairic Coptic: ⲙⲉⲙϥⲓ; Greek: Μέμφις), or Men-nefer, was the ancient capital of Inebu-hedj, the first nome of Lower Egypt that was known as mḥw ("North").

According to legends related in the early third century BC by Manetho, a priest and historian who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom during the Hellenistic period of ancient Egypt, the city was founded by King Menes.

[1] Some scholars maintain that this name was that of an area that contained a sacred tree, the western district of the city that lay between the great Temple of Ptah and the necropolis at Saqqara.

The modern cities and towns of Mit Rahina, Dahshur, Abusir, Abu Gorab, and Zawyet el'Aryan, south of Cairo, all lie within the administrative borders of historical Memphis (29°50′58.8″N 31°15′15.4″E / 29.849667°N 31.254278°E / 29.849667; 31.254278).

The complex of Djoser of the Third Dynasty, located in the ancient necropolis at Saqqara, would then be the royal funerary chamber, housing all the elements necessary to royalty: temples, shrines, ceremonial courts, palaces, and barracks.

The golden age began with the Fourth Dynasty, which seems to have furthered the primary role of Memphis as a royal residence where rulers received the double crown, the divine manifestation of the unification of the Two Lands.

Although the seat of political power had shifted, Memphis did remain perhaps the most important commercial and artistic centre, as evidenced by the discovery of handicrafts districts and cemeteries, located west of the temple of Ptah.

These kings were also known to have ordered mining expeditions, raids, or military campaigns beyond the borders, erecting monuments or statues to the consecration of deities, evinced by a panel recording official acts of the royal court during this time.

[Fnt 2] Evidence of royal propaganda has been uncovered and attributed to the Theban kings of the Seventeenth Dynasty, who initiated the reconquest of the kingdom half a century later.

Strengthening trade ties with other empires made the nearby port of Peru-nefer (literally, "Good Travels" or "Bon Voyage") the gateway to the kingdom for neighbouring regions, including Byblos and the Levant.

During his exploration of the site, Karl Richard Lepsius identified a series of blocks and broken colonnades in the name of Thutmose IV to the east of the Temple of Ptah.

[42] His successor Tutankhamun (r. 1332–1323 BC; formerly Tutankhaten) relocated the royal court from Akhenaten's capital Akhetaten ("Horizon of the Aten") to Memphis before the end of the second year of his reign.

The funerary cult surrounding this monument, well known in the New Kingdom, was still functioning several generations after its establishment at the temple, leading some scholars to suggest that it may have contained the royal burial chamber of the king.

In a massive invasion in 664 BC, the city of Memphis was again sacked and looted, and the king Tantamani was pursued into Nubia and defeated, putting a definitive end to the Kushite reign over Egypt.

Power then returned to the Saite kings, who, fearful of an invasion from the Babylonians, reconstructed and even fortified structures in the city, as is attested by the palace built by Apries at Kom Tuman.

For almost a century and a half, the city remained the capital of the Persian satrapy of Egypt ("Mudraya"/"Musraya"), officially becoming one of the epicentres of commerce in the vast territory conquered by the Achaemenid monarchy.

As in the Late Period, the catacombs in which the remains of the sacred bulls were buried gradually grew in size, and later took on a monumental appearance that confirms the growth of the cult's hypostases throughout the country, and particularly in Memphis and its necropolis.

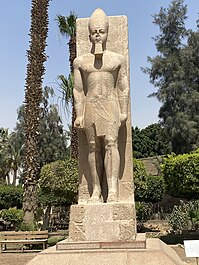

Nectanebo II meanwhile, while continuing the work of his predecessor, began building large sanctuaries, especially in the necropolis of Saqqara, adorning them with pylons, statues, and paved roads lined with rows of sphinxes.

From this period date many developments of the Saqqara Serapeum, including the building of the Chamber of Poets, as well as the dromos adorning the temple, and many elements of Greek-inspired architecture.

Delegates from the principal clergies of the kingdom gathered in synod, under the patronage of the High Priest of Ptah and in the presence of the king, to establish the religious policy of the country for years to come, also dictating fees and taxes, creating new foundations, and paying tribute to the Ptolemaic rulers.

Enormous as are the extent and antiquity of this city, in spite of the frequent change of governments whose yoke it has borne, and the great pains more than one nation has been at to destroy it, to sweep its last trace from the face of the earth, to carry away the stones and materials of which it was constructed, to mutilate the statues which adorned it; in spite, finally, of all that more than four thousand years have done in addition to man, these ruins still offer to the eye of the beholder a mass of marvels which bewilder the senses and which the most skillful pens must fail to describe.

The excavations uncovered a religious building complete with a tower, a courtyard for ritual offerings, a portico with columns followed by a pillared hall and a tripartite sanctuary, all enclosed in walls built of mudbricks.

The archaeological explorations that took place here reveal that the southern part of the city indeed contain a large number of religious buildings with a particular devotion to the god Ptah, the principal deity of Memphis.

In the southeast of the Great Temple complex, the king Merneptah of the Nineteenth Dynasty founded a new shrine in honour of the chief deity of the city, Ptah.

It may be located within the precinct of the Hout-ka-Ptah, as would seem to suggest several discoveries made among the ruins of the complex in the late nineteenth century, including a block of stone evoking the "great door" with the epithet of the goddess,[53] and a column bearing an inscription on behalf of Ramesses II declaring him "beloved of Sekhmet".

Expansions of the western sector of the temple of Ptah were ordered by the kings of the Twenty-second Dynasty, seeking to revive the past glory of the Ramesside age.

According to sources, the site also included a chapel or an oratory to the goddess Bastet, which seems consistent with the presence of monuments of rulers of the dynasty following the cult of Bubastis.

Among the major sources from this time: In 1652 during his trip to Egypt, Jean de Thévenot identified the location of the site and its ruins, confirming the accounts of the old Arab authors for Europeans.

Here is a partial list: During the British era in Egypt, the development of agricultural technology along with the systematic cultivation of the Nile floodplains led to a considerable amount of accidental archaeological discoveries.

[72][73] From 1852 to 1854, Joseph Hekekyan, then working for the Egyptian government, conducted geological surveys on the site, and on these occasions made a number of discoveries, such as those at Kom el-Khanzir (northeast of the great temple of Ptah).