Mercia

Nicholas Brooks noted that "the Mercians stand out as by far the most successful of the various early Anglo-Saxon peoples until the later ninth century",[3] and some historians, such as Sir Frank Stenton, believe the unification of England south of the Humber estuary was achieved during Offa's reign.

At the end of the 9th century, following the invasions of the Vikings and their Great Heathen Army, Danelaw absorbed much of the former Mercian territory.

Mercia's exact evolution at the start of the Anglo-Saxon era remains more obscure than that of Northumbria, Kent, or even Wessex.

However, Peter Hunter Blair argued an alternative interpretation: that they emerged along the frontier between Northumbria and the inhabitants of the Trent river valley.

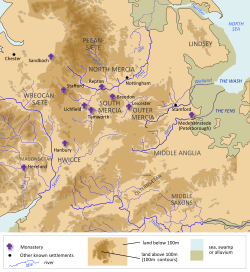

[6] Although its earliest boundaries remain obscure, a general agreement persists that the territory that was called "the first of the Mercians" in the Tribal Hidage covered much of south Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Staffordshire and northern Warwickshire.

[9] The Mercian kings were the only Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy ruling house known to claim a direct family link with a pre-migration Continental Germanic monarchy.

However, Bede admits that Penda freely allowed Christian missionaries from Lindisfarne into Mercia and did not restrain them from preaching.

In 633 Penda and his ally Cadwallon of Gwynedd defeated and killed Edwin, who had become not only ruler of the newly unified Northumbria, but bretwalda, or high king, over the southern kingdoms.

When another Northumbrian king, Oswald, arose and again claimed overlordship of the south, he also suffered defeat and death at the hands of Penda and his allies – in 642 at the Battle of Maserfield.

A Mercian revolt in 658 threw off Northumbrian domination and resulted in the appearance of another son of Penda, Wulfhere, who ruled Mercia as an independent kingdom (though he apparently continued to render tribute to Northumbria for a while) until his death in 675.

But when Wihtred died in 725, and Ine abdicated in 726 to become a monk in Rome, Æthelbald was free to establish Mercia's hegemony over the rest of the Anglo-Saxons south of the Humber.

[16] After the murder of Æthelbald by one of his bodyguards in 757, a civil war broke out which concluded with the victory of Offa, a descendant of Pybba.

Offa (reigned 757 to 796) had to build anew the hegemony which his predecessor had exercised over the southern English, and he did this so successfully that he became the greatest king Mercia had ever known.

Not only did he win battles and dominate Southern England, but also he took an active hand in administering the affairs of his kingdom, founding market towns and overseeing the first major issues of gold coins in Britain; he assumed a role in the administration of the Catholic Church in England (sponsoring the short-lived archbishopric of Lichfield, 787 to 799), and even negotiated with Charlemagne as an equal.

In 821 Coenwulf's brother Ceolwulf succeeded to the Mercian kingship; he demonstrated his military prowess by his attack on and destruction of the fortress of Deganwy in Gwynedd.

[19] Beornwulf was slain while suppressing a revolt amongst the East Angles, and his successor, a former ealdorman named Ludeca (reigned 826–827), met the same fate.

Alfred changed his title from 'king of the West Saxons' to 'king of the Anglo-Saxons' to reflect the acceptance of his overlordship of all southern England not under Danish rule.

[24] Æthelred had married Æthelflæd (c. 870 – 12 June 918), daughter of Alfred the Great of Wessex (r. 871–899), and she assumed power when her husband became ill at some time in the last ten years of his life.

Æthelflæd and her brother continued Alfred's policy of building fortified burhs, and by 918 they had conquered the southern Danelaw in East Anglia and Danish Mercia.

[25] When Æthelflæd died in 918, Ælfwynn, her daughter by Æthelred, succeeded as "Second Lady of the Mercians", but within six months Edward had deprived her of all authority in Mercia and taken her to Wessex.

The first appearance of Christianity in Mercia, however, had come at least thirty years earlier, following the Battle of Cirencester of 628, when Penda incorporated the formerly West Saxon territories of Hwicce into his kingdom.

As in other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, the many small monasteries established by the Mercian kings allowed the political/military and ecclesiastical leadership to consolidate their unity through bonds of kinship.

[37] For knowledge of the internal composition of the Kingdom of Mercia, we must rely on a document of uncertain age (possibly late 7th century), known as the Tribal Hidage – an assessment of the extent (but not the location) of land owned (reckoned in hides), and therefore the military obligations and perhaps taxes due, by each of the Mercian tribes and subject kingdoms by name.

Today, "Mercia" appears in the titles of two regiments, the Mercian Regiment, founded in 2007, which recruits in Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Worcestershire, and parts of Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, and the Royal Mercian and Lancastrian Yeomanry, founded in 1992 as part of the Territorial Army.

There is no authentic indigenous Mercian heraldic device, as heraldry did not develop in any recognizable form until the High Middle Ages.

The cross has been incorporated into a number of coats of arms of Mercian towns, including Tamworth, Leek and Blaby.

[49] The silver double-headed eagle surmounted by a golden three-pronged Saxon crown has been used by several units of the British Army as a heraldic device for Mercia since 1958, including the Mercian Regiment.

[52] The symbol appeared on numerous stations and other company buildings in the region, and was worn as a silver badge by all uniformed employees.

Shippey states further that "the Mark", the land of the Riders of Rohan – all of whom have names in the Mercian dialect of Old English – was once the usual term for central England, and it would have been pronounced and written "marc" rather than the West Saxon "mearc" or the Latinized "Mercia".