Metamaterial

Metamaterials are usually fashioned from multiple materials, such as metals and plastics, and are usually arranged in repeating patterns, at scales that are smaller than the wavelengths of the phenomena they influence.

Appropriately designed metamaterials can affect waves of electromagnetic radiation or sound in a manner not observed in bulk materials.

Potential applications of metamaterials are diverse and include sports equipment[9][10] optical filters, medical devices, remote aerospace applications, sensor detection and infrastructure monitoring, smart solar power management, Lasers,[11] crowd control, radomes, high-frequency battlefield communication and lenses for high-gain antennas, improving ultrasonic sensors, and even shielding structures from earthquakes.

Some of the earliest structures that may be considered metamaterials were studied by Jagadish Chandra Bose, who in 1898 researched substances with chiral properties.

Karl Ferdinand Lindman studied wave interaction with metallic helices as artificial chiral media in the early twentieth century.

[8] In 1995, John M. Guerra fabricated a sub-wavelength transparent grating (later called a photonic metamaterial) having 50 nm lines and spaces, and then coupled it with a standard oil immersion microscope objective (the combination later called a super-lens) to resolve a grating in a silicon wafer also having 50 nm lines and spaces.

[16] In 2000, John Pendry was the first to identify a practical way to make a left-handed metamaterial, a material in which the right-hand rule is not followed.

Pendry's idea was that metallic wires aligned along the direction of a wave could provide negative permittivity (dielectric function ε < 0).

In 2000, David R. Smith et al. reported the experimental demonstration of functioning electromagnetic metamaterials by horizontally stacking, periodically, split-ring resonators and thin wire structures.

In 2003, complex (both real and imaginary parts of) negative refractive index[22] and imaging by flat lens[23] using left handed metamaterials were demonstrated.

Fundamentally, the key metrics for diffusion and wave metamaterials present a stark divergence, underscoring a distinct complementary relationship between them.

[citation needed] The unusual properties of metamaterials arise from the resonant response of each constituent element rather than their spatial arrangement into a lattice.

The resonance effect related to the mutual arrangement of elements is responsible for Bragg scattering, which underlies the physics of photonic crystals, another class of electromagnetic materials.

The criterion for shifting the local resonance below the lower Bragg stop-band make it possible to build a photonic phase transition diagram in a parameter space, for example, size and permittivity of the constituent element.

Microwave frequency metamaterials are usually constructed as arrays of electrically conductive elements (such as loops of wire) that have suitable inductive and capacitive characteristics.

Photonic crystals and frequency-selective surfaces such as diffraction gratings, dielectric mirrors and optical coatings exhibit similarities to subwavelength structured metamaterials.

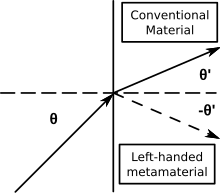

[36][37] Metamaterials with negative n have numerous interesting properties:[4][38] Negative index of refraction derives mathematically from the vector triplet E, H and k.[4] For plane waves propagating in electromagnetic metamaterials, the electric field, magnetic field and wave vector follow a left-hand rule, the reverse of the behavior of conventional optical materials.

EBG application developments include a transmission line, woodpiles made of square dielectric bars and several different types of low gain antennas.

Such decomposition allows us to classify the reciprocal bianisotropic response and we can identify the following three main classes: (i) chiral media (

[citation needed] Acoustic metamaterials control, direct and manipulate sound in the form of sonic, infrasonic or ultrasonic waves in gases, liquids and solids.

Composite materials with highly aligned internal particles or structures, such as fibers, and carbon nanotubes (CNT), are examples of this.

[67][68][69] In addition, exotic properties such as a negative refractive index, create opportunities to tailor the phase matching conditions that must be satisfied in any nonlinear optical structure.

Later in 2015 Muamer Kadic et al.[72] showed that a simple perforation of isotropic material can lead to its change of sign of the Hall coefficient.

Engineered at the nanoscale, these materials adeptly manipulate electromagnetic, acoustic, or thermal properties to facilitate biological processes.

Through meticulous adjustment of their structure and composition, meta-biomaterials hold promise in augmenting various biomedical technologies such as medical imaging,[75] drug delivery,[76] and tissue engineering.

[15][87] Materials that can attain negative permeability allow for properties such as small antenna size, high directivity and tunable frequency.

Conventionally, the RCS has been reduced either by radar-absorbent material (RAM) or by purpose shaping of the targets such that the scattered energy can be redirected away from the source.

More recently, metamaterials or metasurfaces are synthesized that can redirect the scattered energy away from the source using either array theory[100][101][102][103] or generalized Snell's law.

[12][106][107] Metamaterials textured with nanoscale wrinkles could control sound or light signals, such as changing a material's color or improving ultrasound resolution.

[113] Other applications such as integrated mode converters,[114] polarization (de)multiplexers,[115] structured light generation,[116] and on-chip bio-sensors[117] can be developed.