Mexican muralism

[5] Atl also organized an independent exhibition of native Mexican artists promoting many indigenous and national themes along with color schemes that would later appear in mural painting.

[7] Another influence on the young artists of the late Porfirian period was the graphic work of José Guadalupe Posada, who mocked European styles and created cartoons with social and political criticism.

They promoted a populist philosophy that coincided with the social and political criticism of Atl and Posada and influenced the next generation of painters such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

As the country underwent this reformation, General Obregón realized that the reconstruction of a post-revolution Mexico would require a comprehensive alteration of symbols associated with Mexican identity on both cultural and political grounds.

Shortly after the wars end, Obregón appointed José Vasconcelos to act as the Secretaría de Educación Pública, or Minister of Public Education.

In his efforts to help raise a sense of nationalism and promote the inclusion of the masses in political and social ideologies, it was Vasconcelos' idea to have a government-backed mural project.

The government began to hire the country's best artists to paint murals, calling some of them home from their time in Europe, including Diego Rivera.

The first government sponsored mural project was on the three levels of interior walls of the old Jesuit institution Colegio San Ildefonso, at that time used for the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria.

[11] Rivera also contributed his first-ever government-backed mural to the National Preparatory School in 1922 called Creation, functioning as an allegorical depiction of the holy trinity representing love, hope, and faith.

[13] The inception and early years of Mexico's muralist movement are often considered the most ideologically pure and untainted by contradictions between socialist ideals and government manipulation.

[15] Mural artists like the Big Three spent the post-revolutionary period developing their work based on the promises of a better future, and with the advent of conservatism they lost their subject and their voice.

[19] A large quantity of murals were produced in most of the country from the 1920s to 1970, generally with themes related to politics and nationalism focused often on the Mexican Revolution, mestizo identity and Mesoamerican cultural history.

[2] Scholar Teresa Meade states that "indigenismo; the glorification of rural and urban labor and the working man, woman, and child; social criticism to the point of ridicule and mockery; and denunciation of the national, and especially, international ruling classes" were also themes present in the murals at this time.

[2] Much of the mural production glorified indigenismo, or the indigenous aspect of Mexican culture as artists of the movement collectively considered it to be an important factor in the reconstruction of a more modern Mexico.

[5] The various reasons for the focus on ancient Mesoamerica may be divided into three basic categories: the desire to glorify the accomplishments of the perceived original cultures of the Mexican nation; the attempt to locate residual pre-Hispanic forms, practices, and beliefs among contemporaneous indigenous peoples; and the study of parallels between the past and present.

[9] By far, the three most influential muralists from the 20th century are Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros, called "los tres grandes" (the three great ones).

To summarize the general types of contributions the Three Greats made, Rivera's works were utopian and idealist, Orozco's were critical and pessimistic, while the most radical of the three was Siqueiros, who heavily focused on a scientific future.

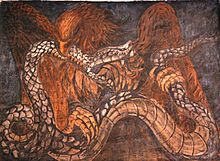

[27] Tamayo was heavily influenced by the early pre-Columbian history of Mexico and it is evident in his piece titled "Nacimiento de Nuestra Nacionalidad".

The center shows a human figure holding a mechanical weapon, sitting atop a horse and surrounded by a glowing light which depicted a 'godlike' Spanish conquistador.

[29] This artwork sits as the final site to be seen, representing Rivera's view of what the Mexican revolution would bring – a free and productive earth in which natural forces being able to be harnessed for the benefit of man.

This form of anonymity functions as commentary towards the war and the soldiers that fought for the revolution – that they will be forgotten, despite their courageous sacrifice in hopes of a brighter future.

Together, these artists aimed to present their belief that the violence of the revolutionary war stemmed from the utilization of the flaw economic system they knew as capitalism, used as a tool of perpetuating the control of fascist leaders.

[16] This piece of art demonstrates the horrors of war, the artists' own negative views toward the role of capitalism during the Revolution, and how the proletariat Mexican citizens were being overlooked and taken advantage of by the Bourgeoise.

This symbolizes a promising future in which Mexico overcomes the obstacles faced in the revolution and embraces technology, as seen in the depictions of electrical towers at the top of the mural.

José Vasconcelos, the Secretary of Public Education under President Álvaro Obregón (1920–24) contracted Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco to pursue painting with the moral and financial support of the new post-revolutionary government.

[32] Vasconcelos, while seeking to promote nationalism and "la raza cósmica," seemed to contradict this sentiment as he guided the muralists to create works in a classic, European style.

[2][34] One recent example is a cross cultural project in 2009 to paint a mural in the municipal market of Teotitlán del Valle, a small town in the state of Oaxaca.

High school and college students from Georgia, United States, collaborated with town authorities to design and paint a mural to promote nutrition, environmental protection, education and the preservation of Zapotec language and customs.

Muralists influenced by Mexican muralism include Carlos Mérida of Guatemala, Oswaldo Guayasamín of Ecuador and Candido Portinari of Brazil.

[2][4] During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration employed artists to paint murals, which paved the way for Mexican muralists to find commissions in the country.