Mickey Mousing

"[3][a] The term comes from the early and mid-production Walt Disney films, where the music almost completely works to mimic the animated motions of the characters.

[11] Mickey Mousing and synchronicity help structure the viewing experience, to indicate how much events should impact the viewer, and to provide information not present on screen.

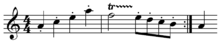

In the 1940 film Fantasia, the musical piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice by Paul Dukas, composed in the 1890s, contains a fragment that is used to accompany the actions of Mickey Mouse himself.

[17] Paul Smith used the technique in several scores for True-Life Adventures documentary films in the fifties, including In Beaver Valley, Nature's Half Acre, Water Birds, and The Olympic Elk.

In Kenneth Branagh's Much Ado About Nothing (1993), Mickey Mousing is used at the opening, with the visual slowed to match the music, producing an intentional lightly comical effect.

[8] The technique is criticized for visual action that is – without good reason – being duplicated in accompanying music or text, therefore being a weakness of the production rather than a strength.

[11] Complaints regarding the technique may be found as early as 1946, when Chuck Jones complained that, "For some reason, many cartoon musicians are more concerned with exact synchronization or 'Mickey-Mousing' than with the originality of their contribution or the variety of their arrangement.

Still, the practice of catching every moment with music has a visual equivalent, and Mickey Mousing has been made to bear the brunt of the criticism for an overobnoxiousness that it only partially creates.