Twelve basic principles of animation

The purpose of squash and stretch[4] is to give a sense of weight and flexibility to drawn or computer-animated objects.

It can be applied to simple objects, like a bouncing ball, or more complex constructions, like the musculature of a human face.

[7] In realistic animation, however, the most important aspect of this principle is that an object's volume does not change when squashed or stretched.

If the length of a ball is stretched vertically, its width (in three dimensions, also its depth) needs to contract correspondingly horizontally.

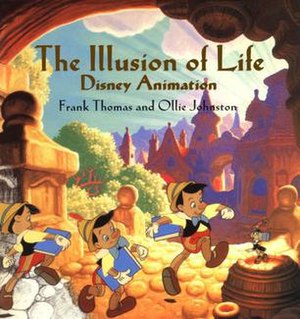

[11] Its purpose is to direct the audience's attention, and make it clear what is of greatest importance in a scene;[12] Johnston and Thomas defined it as "the presentation of any idea so that it is completely and unmistakably clear", whether that idea is an action, a personality, an expression, or a mood.

"Follow through" means that loosely tied parts of a body should continue moving after the character has stopped and the parts should keep moving beyond the point where the character stopped only to be subsequently "pulled back" towards the center of mass or exhibiting various degrees of oscillation damping.

A third, related technique is "drag", where a character starts to move and parts of them take a few frames to catch up.

Inversely, fewer pictures are drawn within the middle of the animation to emphasize faster action.

[23] As an object's speed or momentum increases, arcs tend to flatten out in moving ahead and broaden in turns.

Traditional animators tend to draw the arc in lightly on the paper for reference, to be erased later.

The classical definition of exaggeration, employed by Disney, was to remain true to reality, just presenting it in a wilder, more extreme form.

[29] Other forms of exaggeration can involve the supernatural or surreal, alterations in the physical features of a character; or elements in the storyline itself.

[31] The principle of solid drawing means taking into account forms in three-dimensional space, or giving them volume and weight.

[12] The animator needs to be a skilled artist and has to understand the basics of three-dimensional shapes, anatomy, weight, balance, light and shadow, etc.

[33] One thing in particular that Johnston and Thomas warned against was creating "twins": characters whose left and right sides mirrored each other, and looked lifeless.

[37] A complicated or hard to read face will lack appeal or 'captivation' in the composition of the pose or character design.

rigid, non-dynamic movement of a ball is compared to a "squash" at impact and a "stretch" during the fall and after the bounce. Also, the ball moves less in the beginning and end (the "slow in and slow out" principle).