Microbial symbiosis and immunity

meaning a regular microbiota is necessary for a healthy host immune system as the body is more susceptible to infectious and non-infectious diseases.

[6] When mice are raised in germ-free conditions, they lack circulating antibodies, and cannot produce mucus, antimicrobial proteins, or mucosal T-cells.

Microbes trigger development of isolated lymphoid follicles in the small intestine of humans and mice, which are sites of mucosal immune response.

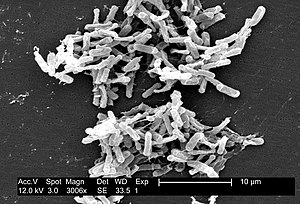

[10] Gram-negative commensal bacteria trigger the development of inducible lymphoid follicles by releasing peptidogylcans containing diaminopimelic acid during cell division.

[13] IgA coats pathogenic bacterial and viral surfaces (immune exclusion), preventing colonization by blocking their attachment to mucosal cells, and can also neutralize PAMPs.

Members of the microbiota are capable of producing antimicrobial peptides, protecting humans from excessive intestinal inflammation and microbial-associated diseases.

This hinders the ability to synthesize the cell wall, resulting in increased membrane permeability, disruption of electrochemical gradients, and possible death.

[23] Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a bacterial species in the ileum and colon, stimulates the gene encoding fucose, Fut2, in intestinal epithelial cells.

[23] In this mutualistic interaction, the intestinal epithelial barrier is fortified and humans are protected against invasion of destructive microbes, while B. thetaiotaomicron benefits because of it can use fucose for energy production and its role in bacterial gene regulation.

Commensal microbes that live on the skin, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, produce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that aid the host immune system.

[26] S. epidermidis and other important microflora work similarly to support homeostasis and general health in areas all over the human body such as the oral cavity, vagina, gastrointestinal tract, and oropharynx.

[28] Gut bacteria metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), B vitamins and N1, N12-diacetylspermine have also been implicated in suppressing colorectal cancer.

[1] Gram-negative bacteria produce lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which binds to TLR-4 and through TGF-β signaling, leads to the expression of growth factors and inflammatory mediators that promote neoplasia.

[28] Members of a healthy gut microbiome have been shown to increase interferon-γ-producing CD8 T-cells and tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells (TILs) in the intestine.

[29] Not only do these CD8 T-cells enhance resistance against intracellular pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes but they also have been shown to be important in anti-cancer immunity specifically against MC38 adenocarcinoma where they along with the TILs increase MHC I expression.

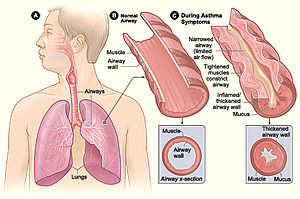

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and asthma are two disorders that have been found to be impacted by microbiota metabolites causing immune reactions.

[1] Inhibition of HDACs downregulates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and the pro-inflammatory tumor necrosis factor (TNF) as well as having anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages and dendritic cells.

Many bacteria cause inflammation in the gut including Escherichia coli, which replicate in macrophages and secretes cytokine tumor necrosis factor.

[34] To mimic colitis and activate inflammatory T cells in an experimental condition, wild-type mice were treated with trinitrobenzen sulphonic acid (TNBS).

[37] SCFAs modulates renin secretion by binding Olfr78, lowering blood pressure and decreasing the risk of kidney disease.

[39] While the exact mechanism by which microbes play a role in obesity has yet to be elucidated, it has been hypothesized that the intestinal microbiota is involved in converting food to usable energy and fat storage.

[39] Gut microbiota impacts many facets of human health, even neurological disorders that can be caused by molecule or hormone imbalance.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD),[1] central nervous system dysfunction[1] and depression[40] have all been found to be impacted by the microbiota.

[41] In the mouse model mice with ASD and GI tract dysbiosis (maternal immune activation) increased intestinal permeability was found as was corrected by the introduction of human gut bacterial symbiont B.