Insect morphology

Individuals can range from 0.3 mm (fairyflies) to 30 cm across (great owlet moth);[1]: 7 have no eyes or many; well-developed wings or none; and legs modified for running, jumping, swimming, or even digging.

The tough and flexible endocuticle is built from numerous layers of fibrous chitin and proteins, crisscrossing each other in a sandwich pattern, while the exocuticle is rigid and sclerotized.

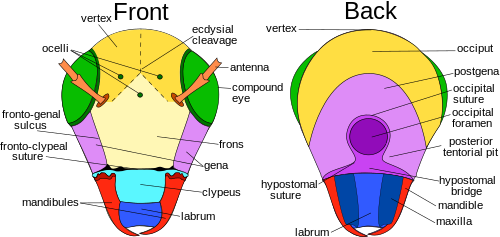

The postgena is the area immediately posteriad, or posterior or lower on the gena of pterygote insects, and forms the lateral and ventral parts of the occipital arch.

It is closed against the mandibles in part by two muscles arising in the head and inserted on the posterior lateral margins on two small sclerites, the tormae, and, at least in some insects, by a resilin spring in the cuticle at the junction of the labrum with the clypeus.

However, recent studies of the embryology, gene expression, and nerve supply to the labrum show it is innervated by the tritocerebrum of the brain, which is the fused ganglia of the third head segment.

With the maxillae, it assists with the manipulation of food during mastication or chewing or, in the unusual case of the dragonfly nymph, extends out to snatch prey back to the head, where the mandibles can eat it.

[27] Most of the hypopharynx is membranous, but the adoral face is sclerotized distally, and proximally contains a pair of suspensory sclerites extending upwards to end in the lateral wall of the stomodeum.

[30] There is an allometric scaling relationship between the body mass of Lepidoptera and length of the proboscis[33] from which an interesting adaptive departure is the unusually long-tongued hawk moth Xanthopan morganii praedicta.

Charles Darwin predicted the existence and proboscis length of this moth before its discovery based on his knowledge of the long-spurred Madagascan star orchid Angraecum sesquipedale.

[34] The mouthparts of insects that feed on fluids are modified in various ways to form a tube through which liquid can be drawn into the mouth and usually another through which saliva passes.

Salivary secretions from the labella assist in dissolving and collecting food particles so they can be more easily taken up by the pseudotracheae or laid their egg on the suitable media; this is thought to occur by capillary action.

Each alinotum (sometimes confusingly referred to as a "notum") may be traversed by sutures that mark the position of internal strengthening ridges and commonly divide the plate into three areas: the anterior prescutum, the scutum, and the smaller posterior scutellum.

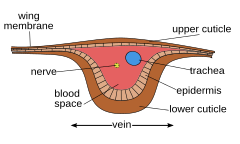

Large numbers of cross-veins are present in some insects, and they may form a reticulum as in the wings of Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) and at the base of the forewings of Tettigonioidea and Acridoidea (katydids and grasshoppers, respectively).

Since all winged insects are believed to have evolved from a common ancestor, the archediction represents the "template" that has been modified (and streamlined) by natural selection for 200 million years.

[1]: 41–42 The four different fields found on insect wings are: Most veins and cross-veins occur in the anterior area of the remigium, which is responsible for most of the flight, powered by the thoracic muscles.

In many Diptera, a deep incision of the anal area of the wing membrane behind the single vannal vein sets off a proximal alar lobe distal to the outer squama of the alula.

The third axillary, therefore, is usually the posterior hinge plate of the wing base and is the active sclerite of the flexor mechanism, which directly manipulates the vannal veins.

The proximal end of the coxa is girdled by a submarginal basicostal suture that forms internally a ridge, or basicosta, and sets off a marginal flange, the coxomarginale, or basicoxite.

In aquatic beetles (Coleoptera) and bugs (Hemiptera), the tibiae and/or tarsi of one or more pairs of legs usually are modified for swimming (natatorial) with fringes of long, slender hairs.

These macromolecules must be broken down by catabolic reactions into smaller molecules like amino acids and simple sugars before being used by cells of the body for energy, growth, or reproduction.

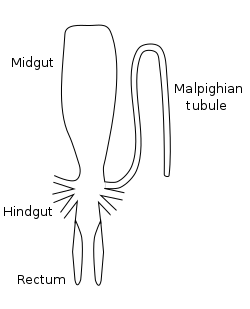

The main structure of an insect's digestive system is a long-enclosed tube called the alimentary canal (or gut), which runs lengthwise through the body.

The foregut includes the buccal cavity (mouth), pharynx, esophagus, and Crop and proventriculus (any part may be highly modified), which both store food and signify when to continue passing onward to the midgut.

[52] In the hindgut (element 16 in numbered diagram), or proctodaeum, undigested food particles are joined by uric acid to form fecal pellets.

The opposite end of the dorsal tube is like the aorta of the insect circulating the hemolymph, arthropods' fluid analog of blood, inside the body cavity.

Making up usually less than 25% of an insect's body weight, it transports hormones, nutrients and wastes and has a role in, osmoregulation, temperature control, immunity, storage (water, carbohydrates and fats) and skeletal function.

The more primitive apterygote insects have a single testis, and in some lepidopterans the two maturing testes are secondarily fused into one structure during the later stages of larval development, although the ducts leading from them remain separate.

[8] For means of finding a mate also, fireflies (Lampyridae) utilized modified fat body cells with transparent surfaces backed with reflective uric acid crystals to biosynthetically produce light, or bioluminescence.

The Ground beetle's (of Carabidae) defensive glands, located at the posterior, produce a variety of hydrocarbons, aldehydes, phenols, quinones, esters, and acids released from an opening at the end of the abdomen.

[71] Larval flies, or maggots, have no true legs, and little demarcation between the thorax and abdomen; in the more derived species, the head is not distinguishable from the rest of the body.

In the digestive system, the anterior region of the foregut has been modified to form a pharyngeal sucking pump as they need it for the food they eat, which are for the most part liquids.

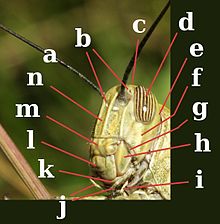

Legend of body parts

Tagmata: A – Head, B – Thorax, C – Abdomen.

- antenna

- ocelli (lower)

- ocelli (upper)

- compound eye

- brain (cerebral ganglia )

- prothorax

- dorsal blood vessel

- tracheal tubes (trunk with spiracle )

- mesothorax

- metathorax

- forewing

- hindwing

- mid-gut (stomach)

- dorsal tube (heart)

- ovary

- hind-gut (intestine, rectum & anus)

- anus

- oviduct

- nerve cord (abdominal ganglia)

- Malpighian tubes

- tarsal pads

- claws

- tarsus

- tibia

- femur

- trochanter

- fore-gut (crop, gizzard)

- thoracic ganglion

- coxa

- salivary gland

- subesophageal ganglion

- mouthparts

Legend: a – antennae

c – compound eye

lb – labium

lr – labrum

md – mandibles

mx – maxillae