Milcah Martha Moore

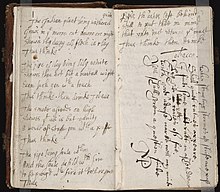

Women of the period used commonplace books as a method of creating a private, informal historical record of their own era, collecting in them aphorisms, quotations, advice, poems, letters, reminiscences, recipes, and other materials of personal significance.

About half of the poems are by Moore's second cousin Hannah Griffitts, while many of the rest are by Susanna Wright and Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, who are considered three of the era's most talented women writers of the eastern seaboard.

Apart from poems, there are extracts from a journal kept by Fergusson during a trip to England as well as some passages copied from the works of Benjamin Franklin, Patrick Henry, and Samuel Fothergill.

[6] With their strongly moral tone and striving towards personal improvement, it has been suggested that compendia such as Moore's were precursors to the advice columns that would become a staple of 19th century newspapers, and which had just begun to appear in the early republic.

[8] Scholars Catherine La Courreye Blecki and Karin A. Wulf, who edited the book for publication, consider it "the richest surviving body of evidence revealing the nature and substance of women's intellectual community in British America.

"[9] In general, scholars of the period similarly value it for its contribution to understanding of the role of Quaker women in late 18th century American political and cultural life.