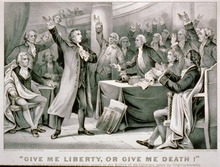

Patrick Henry

He gained further popularity among the people of Virginia, both through his oratory at the convention and by marching troops towards the colonial capital of Williamsburg after the Gunpowder Incident until the munitions seized by the royal government were paid for.

[6] Since the family's stock, considerable lands, and slaves would pass to his older half-brother John Syme Jr.,[7] due to the custom of primogeniture, Henry needed to make his own way in the world.

Five clergymen then brought suit for back pay, cases known as the Parson's Cause; of them, only the Reverend James Maury was successful, and a jury was to be empaneled in Hanover County on December 1, 1763, to fix damages.

[24] In the wake of the Parson's Cause, Henry began to gain a following in backwoods Virginia because of his oratory defending the liberties of the common people and thanks to his friendly manner.

John Tyler Sr. (father of the future president), who was standing with Jefferson as they watched the session, called this one of "the trying moments which is decisive of character", and both recalled that Henry did not waver: "If this be treason, make the most of it!".

[36] On May 31, with Henry absent and likely returning home, the Burgesses expunged the fifth resolution, and Royal Governor Francis Fauquier refused to allow any of them to be printed in the official newspaper, the Virginia Gazette.

Although the lack of a legislative session sidelined Henry during the crisis, it also undermined the established leaders of the chamber, who remained scattered through the colony with little opportunity to confer as the public rage for change grew hotter.

Income from land deals in 1771 enabled him to buy Scotchtown, a large plantation in Hanover County, which he purchased from John Payne, the father of Dolley Madison—she lived there for a brief time as a child.

[46] Henry professed that slavery was wrong and expressed hopes for its abolition, but he had no plan for doing so nor for the multiracial society that would result, for he did not believe schemes to settle freed slaves in Africa were realistic, "to re-export them is now impracticable, and sorry I am for it.

The Burgesses wanted to rebuke Dunmore for his actions, and Henry was part of a committee of eight that drafted a resolution thanking the governor for the capture of the gang but affirming that using the "usual mode" of criminal procedure protected both the guilty and the innocent.

[61] Silas Deane of Connecticut described Henry as "the compleatest speaker I ever heard ... but in a Letter I can give You no Idea of the Music of his Voice, or the highwrought, yet Natural elegance of his Stile, or Manner".

"[65] Henry lost the argument, and his theatrics made Congress's leaders afraid he would be unpredictable if placed on the lead committee charged with composing a statement regarding colonial rights.

[68] After the birth of their sixth child in 1771, Patrick's wife Sarah Shelton Henry began to exhibit symptoms of mental illness, and one reason for the move from Louisa County to Scotchtown was so they could be near family members.

Henry wrote to all county lieutenants, stating that the proclamation "is fatal to the publick Safety" and urging an "unremitting Attention to the Government of the SLAVES may, I hope, counteract this dangerous Attempt.

When the draft was debated, Henry, at the request of a young delegate from Orange County, James Madison, produced an amendment changing Mason's call for religious tolerance to one requiring full freedom of religion.

[103][105] Desertion was also a problem Henry labored to solve with limited success; many Virginians had been induced to enlist with promises they would not be sent outside the state or local area, and they left when orders came to march.

President Washington wrote of Henry in 1794, "I have always respected and esteemed him; nay more, I have conceived myself under obligation to him for the friendly manner in which he transmitted to me some insidious anonymous writings in the close of the year 1777 with a view to embark him in the opposition that was forming against me at that time".

None was forthcoming,[112] and on May 8, 1779, in the final days of Henry's governorship, British ships under Sir George Collier entered the bay, landed troops, and took Portsmouth and Suffolk, destroying valuable supplies.

[116] In January 1781, British forces under the renegade former American general, Benedict Arnold, sailed up the James River and captured Richmond with little opposition as Henry joined the other legislators and Governor Jefferson in fleeing to Charlottesville.

During this time, Henry and his family lived at "Salisbury", in Chesterfield County, about 13 miles (21 km) from Richmond[128] in open country that he rented, though he had an official residence close to the Virginia Capitol, which was then under construction.

[131] Although Henry urged leniency in his report to the General Assembly that October, stating that the Washington County separatists had been led astray by anxiety because of the poor economy,[132] he had the legislature pass a Treason Act forbidding the setting-up of a rival government within Virginia territory.

Despite Henry's support for internal improvements, he failed to notify Virginia's representatives of their appointment to meet with Maryland over navigation on the Potomac, and only two, including George Mason, attended what became known as the Mount Vernon Conference in 1785.

Governor Randolph offered to make Henry a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, scheduled to meet in Philadelphia later that year to consider changes to the Articles of Confederation, the document that had governed the loose union among the states since 1777.

Several factors had eroded Henry's trust in the Northern states, including what he deemed Congress's failure to send adequate troops to protect Virginia settlers in the Ohio River Valley.

[156] A final cause Henry engaged in before leaving the House of Delegates at the end of 1790[1] was over the Funding Act of 1790, by which the federal government took over the debts of the states, much of which dated from the Revolutionary War.

[158] Leaving the House of Delegates after 1790, Henry found himself in debt, owing in part to expenses while governor, and sought to secure his family's fortune through land speculation and a return to the practice of law.

If any are disposed to censure Mr. Henry for his late political transition [to supporting the Federalists], if anything has been written on that subject, let the Genius of American Independence drop a tear, and blot it out forever.

According to the college, "Bishop Emory symbolizes belief in the union of faith and learning, while Governor Henry represents the commitment to the ideals of freedom and civic virtue.

[193] According to Tate, "by his unmatched oratorical powers, by employing a certain common touch to win the unwavering loyalty of his constituents, and by closely identifying with their interests, he almost certainly contributed to making the Revolution a more widely popular movement than it might otherwise have become".

[191] During the Civil War era, both sides claimed Henry as a partisan, abolitionists citing his writings against slavery, and those sympathetic to the Southern cause pointing to his hostility to the Constitution.