Military history of the Song dynasty

Let’s first make the inspector general the Son of Heaven, and then proceed on the northern expedition.” Because he had consumed much food and drink at the farewell banquet, Taizu was sleeping drunk in his chamber and so was unaware of their plans.

Song troops under Pan Mei, Cao Bin, and Yang Ye were defeated by a Liao army led personally by Empress Dowager Chengtian.

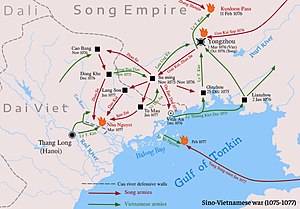

[35] Lý–Song War: In November 1075, Vietnamese generals Lý Thường Kiệt and Nùng Tông Đán invaded the Song dynasty with 63,000 troops, capturing Qinzhou, Lianzhou, and destroying Yongzhou before retreating.

[36][37] Emperor Shenzong proclaimed that “the [Vietnamese] king Lý Càn Đức has revolted and attacked my fortresses and towns.” Nine armies were dispatched to “end this tyrannical mode of government".

Because You, Ji, Yun, and Shuo [the Sixteen Prefectures] are in the hands of the Khitans; Lingwu and Hexi [in the northwest] are under the sole command of the [Tanguts]; and Cochin and Annam [in the far south] are controlled by the Ly family, it is no longer possible to establish bureaucrats there, nor to exact taxes or corvée labor.

The result has been that military men on the frontier – who lie in wait for small gains, wantonly talking big and taking credit for the achievements of others without regard for the harm done to the state – vie to show off their bravado .

And pasty-faced bookworms – steeped in texts and diagrams, who delight in ancient precedents without a sense of how to adapt them to contemporary circumstances – compete with each other to present bizarre policy proposals at court.

The men of Suzhou 宿州 (in northern Anhui) who were drafted as sailors, found no place where they could make their complaints, and in desperation they assaulted and killed the magistrate and his servants, before they left.

However, after the beginning of Emperor Taizong of Song's reign (r. 15 November 976 – 8 May 997), military organization was localized to the commandery level for all practical troop movements, fortifications, and battles.

[150] Song crossbowmen constituted their own separate units apart from the infantry, and according to the Chinese Wujing Zongyao military manuscript of 1044, the crossbow used in mass was the most effective weapon used against northern nomadic cavalry charges.

[151] Song cavalry used an array of different weapons, including halberds, swords, bows, and fire lances that discharged a gunpowder blast of flame and shrapnel.

[143] There were sixteen known varieties of catapults in the Song period, designed to fit many different proportions and requiring work crews in sizes ranging from dozens to several hundred men.

[155]Due to the lack of their own cavalry forces, the Song army usually had to rely on anti-cavalry infantry equipped with "horse-butchering sabres", large axes, and crossbows to overcome the Khitans and Jurchens.

However, after the unsuccessful invasion of Dai Viet in 981, the Song gradually lost interest in the navy, although Guangnan Circuit maintained a "Convoy Escort Squadron" (jiagang shuijun) which accompanied and protected incoming and outgoing merchant ships.

[174] During the Song dynasty (960–1279) it became fashionable to create warts on pieces of armour to imitate cold forged steel, a product typically produced by non-Han people in modern Qinghai.

In a similar vein, Yin Zhu deplored the inadequate training of archers and crossbow men in critical short-spear, iron whip, and sword techniques, rendering them impotent and vulnerable in the close-combat situations that Shaanxi's topography made inevitable.

"[179] Both Tang and Song manuals also made aware to the reader that "the accumulated arrows should be shot in a stream, which means that in front of them there must be no standing troops, and across [from them] no horizontal formations.

The History of Song elaborates on the battle in detail: [Wu] Jie ordered his commanders to select their most vigorous bowmen and strongest crossbowmen and to divide them up for alternate shooting by turns (分番迭射).

[27][28] The Wujing Zongyao served as a repository of antiquated or fanciful weaponry, and this applied to gunpowder as well, suggesting that it had already been weaponized long before the invention of what would today be considered conventional firearms.

The earliest confirmed employment of the fire lance in warfare was by Song dynasty forces against the Jin in 1132 during the siege of De'an (modern Anlu, Hubei Province).

Song commander Wei Sheng constructed several hundred of these carts known as "at-your-desire-war-carts" (如意戰車), which contained fire lances protruding from protective covering on the sides.

The Song commander "ordered that gunpowder arrows be shot from all sides, and wherever they struck, flames and smoke rose up in swirls, setting fire to several hundred vessels.

[195]According to a minor military official by the name of Zhao Wannian (趙萬年), thunderclap bombs were used again to great effect by the Song during the Jin siege of Xiangyang in 1206–1207.

Jin troops were surprised in their encampment while asleep by loud drumming, followed by an onslaught of crossbow bolts, and then thunderclap bombs, which caused a panic of such magnitude that they were unable to even saddle themselves and trampled over each other trying to get away.

Not only does the inscription contain the era name and date, it also includes a serial number and manufacturing information which suggests that gun production had already become systematized, or at least become a somewhat standardized affair by the time of its fabrication.

The Mongol war machine moved south and in 1237 attacked the Song city of Anfeng (modern Shouxian, Anhui Province) "using gunpowder bombs [huo pao] to burn the [defensive] towers.

"[106] The Song defenders under commander Du Gao (杜杲) rebuilt the towers and retaliated with their own bombs, which they called the "Elipao," after a famous local pear, probably in reference to the shape of the weapon.

[193] The next major battle to feature gunpowder weapons was during a campaign led by the Mongol general Bayan, who commanded an army of around two hundred thousand, consisting of mostly Chinese soldiers.

Thus Bayan waited for the wind to change to a northerly course before ordering his artillerists to begin bombarding the city with molten metal bombs, which caused such a fire that "the buildings were burned up and the smoke and flames rose up to heaven.

"[193] This didn't work and the city resisted anyway, so the Mongol army bombarded them with fire bombs before storming the walls, after which followed an immense slaughter claiming the lives of a quarter million.