Thutmose III

"[1][12] Manetho in his Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt) written in Greek and paraphrased by Eusebius called him Miphrês (Μίφρης) and Misphragmuthôsis (Μισφραγμούθωσις.

[4] When Thutmose III reached a suitable age and demonstrated his capacity, Hatshepsut appointed him to head her armies, and at her death in 1458, he was ready to rule.

She was the mother of several of his children, including the future king Amenhotep II and another son, Menkheperre, and at least four daughters: Nebetiunet, Meritamen C and D and Iset.

This document has no note of the place of observation,[citation needed] but it can safely be assumed that it was taken in either a Delta city, such as Memphis or Heliopolis, or in Thebes.

He transformed Egypt into an international superpower, an empire stretching from the Asian regions of Syria in the North, to Upper Nubia in the south.

[29] When Hatshepsut died on the 10th day of the sixth month of Thutmose III's 21st year, according to a stela from Armant, the king of Kadesh advanced his army to Megiddo.

[30] Thutmose III mustered his own army and marched from Egypt, passing through the border fortress of Tjaru (Sile) on the 25th day of the eighth month.

The army moved through the coastal plain as far as Jamnia, then turned inland, reaching Yehem, a small city near Megiddo, in the middle of the ninth month of the same year.

A ridge of mountains jutting inland from Mount Carmel stood between Thutmose and Megiddo and he had three attack routes to choose from.

By taking Megiddo, Thutmose gained control of all of northern Canaan, forcing the Syrian princes to send tribute and noble hostages to Egypt.

[38] Beyond the Euphrates, the Assyrian, Babylonian and Hittite kings honored Thutmose with gifts, which he claimed as "tribute" on the walls of Karnak.

[44] No record remains of Thutmose's fourth campaign,[45] but at some point a fort was built in lower Lebanon and timber was cut for construction of a processional barque, and this probably fits best during this time frame.

Unlike previous plundering raids, Thutmose III garrisoned Djahy, a name which probably refers to southern Syria.

The policy of these cities was driven by their nobles, aligned to Mitanni and typically consisting of a king and a small number of foreign Maryannu.

[51] After Thutmose III had taken control of the Syrian cities, the obvious target for his eighth campaign was the state of Mitanni, a Hurrian country with an Indo-Aryan ruling class.

[55] He continued north through the territory belonging to the still unconquered cities of Aleppo and Carchemish and quickly crossed the Euphrates in his boats, taking the Mitannian king entirely by surprise.

[54] Thutmose III returned to Syria for his ninth campaign in his 34th year, but this appears to have been just a raid of the area called Nukhashshe, a region populated by semi-nomadic people.

As usual for any Egyptian king, Thutmose boasted a total crushing victory, but this statement is suspect due to the very small amount of plunder taken.

Thutmose's architects and artisans showed great continuity with the formal style of previous kings, but several developments set him apart from his predecessors.

[70] Although not directly pertaining to his monuments, it appears that Thutmose's artisans had learned glass making skills, developed in the early 18th Dynasty, to create drinking vessels by the core-formed method.

[77] Some time after her death, many of Hatshepsut's monuments and depictions were defaced or destroyed, including those in her famous mortuary temple complex at Deir el-Bahri.

These were interpreted by early modern scholars as damnatio memoriae (erasure from recorded existence) by Thutmose III in a fit of vengeful rage shortly after his accession.

Scholars such as Charles Nims and Peter Dorman have re-examined the erasures and found that those which could be dated only began during year 46 or 47, toward the end of Thutmose's reign (c. 1433/2 BC).

By the time the monuments of Hatshepsut were damaged, at least 25 years after her death, the elderly Thutmose III was in a coregency with his son Amenhotep II.

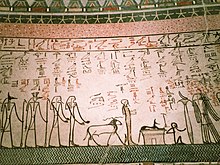

The colouring is similarly muted, executed in simple black figures accompanied by text on a cream background with highlights in red and pink.

It was unwrapped soon after its arrival in the Boulak Museum while Maspero was away in France, and the Director General of the Egyptian Antiquities Service ordered the mummy re-wrapped.

[84] Maspero's description of the body provides an idea as to the severity of the damage: His mummy was not securely hidden away, for towards the close of the 20th dynasty it was torn out of the coffin by robbers, who stripped it and rifled it of the jewels with which it was covered, injuring it in their haste to carry away the spoil.

His statues, though not representing him as a type of manly beauty, yet give him refined, intelligent features, but a comparison with the mummy shows that the artists have idealised their model.

The forehead is abnormally low, the eyes deeply sunk, the jaw heavy, the lips thick, and the cheek-bones extremely prominent; the whole recalling the physiognomy of Thûtmosis II, though with a greater show of energy.

[84] Unlike many other examples from the Deir el-Bahri Cache, the wooden mummiform coffin that contained the body was original to the pharaoh, though any gilding or decoration it might have had had been hacked off in antiquity.