Europa (moon)

[21] In addition, the Hubble Space Telescope detected water vapor plumes similar to those observed on Saturn's moon Enceladus, which are thought to be caused by erupting cryogeysers.

[22] In May 2018, astronomers provided supporting evidence of water plume activity on Europa, based on an updated analysis of data obtained from the Galileo space probe, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003.

The European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) is a mission to Ganymede launched on 14 April 2023, that will include two flybys of Europa.

[31][32] Europa, along with Jupiter's three other large moons, Io, Ganymede, and Callisto, was discovered by Galileo Galilei on 8 January 1610,[2] and possibly independently by Simon Marius.

[33] The naming scheme was suggested by Simon Marius,[34] who attributed the proposal to Johannes Kepler:[34][35] Jupiter is much blamed by the poets on account of his irregular loves.

I think, therefore, that I shall not have done amiss if the First is called by me Io, the Second Europa, the Third, on account of its majesty of light, Ganymede, the Fourth Callisto...[36][37]The names fell out of favor for a considerable time and were not revived in general use until the mid-20th century.

[42] Thus, the tidal flexing kneads Europa's interior and gives it a source of heat, possibly allowing its ocean to stay liquid while driving subsurface geological processes.

Recent magnetic-field data from the Galileo orbiter showed that Europa has an induced magnetic field through interaction with Jupiter's, which suggests the presence of a subsurface conductive layer.

Portions of the crust are estimated to have undergone a rotation of nearly 80°, nearly flipping over (see true polar wander), which would be unlikely if the ice were solidly attached to the mantle.

[58] The ionizing radiation level at Europa's surface is equivalent to a daily dose of about 5.4 Sv (540 rem),[59] an amount that would cause severe illness or death in human beings exposed for a single Earth day (24 hours).

[61] Europa's most striking surface features are a series of dark streaks crisscrossing the entire globe, called lineae (English: lines).

[72] An alternative hypothesis suggests that lenticulae are actually small areas of chaos and that the claimed pits, spots and domes are artefacts resulting from the over-interpretation of early, low-resolution Galileo images.

[77] Work published by researchers from Williams College suggests that chaos terrain may represent sites where impacting comets penetrated through the ice crust and into an underlying ocean.

Most geologists who have studied Europa favor what is commonly called the "thick ice" model, in which the ocean has rarely, if ever, directly interacted with the present surface.

[88] Spectrographic evidence suggests that the darker, reddish streaks and features on Europa's surface may be rich in salts such as magnesium sulfate, deposited by evaporating water that emerged from within.

[93][94][95] The morphology of Europa's impact craters and ridges is suggestive of fluidized material welling up from the fractures where pyrolysis and radiolysis take place.

Impurities in the water ice crust of Europa are presumed both to emerge from the interior as cryovolcanic events that resurface the body, and to accumulate from space as interplanetary dust.

[96][97][98] The presence of sodium chloride in the internal ocean has been suggested by a 450 nm absorption feature, characteristic of irradiated NaCl crystals, that has been spotted in HST observations of the chaos regions, presumed to be areas of recent subsurface upwelling.

For the current axial tilt estimate of 0.1 degree, the resonance from Rossby waves would contain 7.3×1018 J of kinetic energy, which is two thousand times larger than that of the flow excited by the dominant tidal forces.

[106] Europa's seafloor could be heated by the moon's constant flexing, driving hydrothermal activity similar to undersea volcanoes in Earth's oceans.

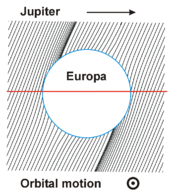

[116][117][118] It has been suggested that if plumes exist, they are episodic[119] and likely to appear when Europa is at its farthest point from Jupiter, in agreement with tidal force modeling predictions.

[121][122] In May 2018, astronomers provided supporting evidence of water plume activity on Europa, based on an updated critical analysis of data obtained from the Galileo space probe, which orbited Jupiter between 1995 and 2003.

[121][125][126] In November 2020, a study was published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters suggesting that the plumes may originate from water within the crust of Europa as opposed to its subsurface ocean.

The hypothesis that cryovolcanism on Europa could be triggered by freezing and pressurization of liquid pockets in the icy crust was first proposed by Sarah Fagents at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, who in 2003, was the first to model and publish work on this process.

[127] A press release from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory referencing the November 2020 study suggested that plumes sourced from migrating liquid pockets could potentially be less hospitable to life.

The atmosphere of Europa can be categorized as thin and tenuous (often called an exosphere), primarily composed of oxygen and trace amounts of water vapor.

On 13 January 2014, the House Appropriations Committee announced a new bipartisan bill that includes $80 million in funding to continue the Europa mission concept studies.

[51] More ambitious ideas have been put forward including an impactor in combination with a thermal drill to search for biosignatures that might be frozen in the shallow subsurface.

[186] The energy provided by tidal forces drives active geological processes within Europa's interior, just as they do to a far more obvious degree on its sister moon Io.

[193] Some scientists have speculated that life on Earth could have been blasted into space by asteroid collisions and arrived on the moons of Jupiter in a process called lithopanspermia.