Mirror

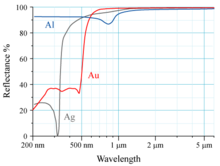

In modern mirrors, metals like silver or aluminium are often used due to their high reflectivity, applied as a thin coating on glass because of its naturally smooth and very hard surface.

This property, called specular reflection, distinguishes a mirror from objects that diffuse light, breaking up the wave and scattering it in many directions (such as flat-white paint).

Objects such as walls, ceilings, or natural rock-formations may produce echos, and this tendency often becomes a problem in acoustical engineering when designing houses, auditoriums, or recording studios.

[17] The Roman scholar Pliny the Elder claims that artisans in Sidon (modern-day Lebanon) were producing glass mirrors coated with lead or gold leaf in the back.

A better method, developed in Germany and perfected in Venice by the 16th century, was to blow a cylinder of glass, cut off the ends, slice it along its length, and unroll it onto a flat hot plate.

During the early European Renaissance, a fire-gilding technique developed to produce an even and highly reflective tin coating for glass mirrors.

For example, in the late seventeenth century, the Countess de Fiesque was reported to have traded an entire wheat farm for a mirror, considering it a bargain.

French workshops succeeded in large-scale industrialization of the process, eventually making mirrors affordable to the masses, in spite of the toxicity of mercury's vapor.

[31] Mirrors can be classified in many ways; including by shape, support, reflective materials, manufacturing methods, and intended application.

Mirrors that are meant to precisely concentrate parallel rays of light into a point are usually made in the shape of a paraboloid of revolution instead; they are used in telescopes (from radio waves to X-rays), in antennas to communicate with broadcast satellites, and in solar furnaces.

[32] The most common structural material for mirrors is glass, due to its transparency, ease of fabrication, rigidity, hardness, and ability to take a smooth finish.

[36] In flying relativistic mirrors conceived for X-ray lasers, the reflecting surface is a spherical shockwave (wake wave) created in a low-density plasma by a very intense laser-pulse, and moving at an extremely high velocity.

[41] This property can be explained by the physics of an electromagnetic plane wave that is incident to a flat surface that is electrically conductive or where the speed of light changes abruptly, as between two materials with different indices of refraction.

Dielectric materials are typically very hard and relatively cheap, however the number of coats needed generally makes it an expensive process.

In mirrors with low tolerances, the coating thickness may be reduced to save cost, and simply covered with paint to absorb transmission.

Precision ground and polished mirrors intended for lasers or telescopes may have tolerances as high as λ/50 (1/50 of the wavelength of the light, or around 12 nm) across the entire surface.

[45][44] The surface quality can be affected by factors such as temperature changes, internal stress in the substrate, or even bending effects that occur when combining materials with different coefficients of thermal expansion, similar to a bimetallic strip.

For wavelengths that are approaching or are even shorter than the diameter of the atoms, such as X-rays, specular reflection can only be produced by surfaces that are at a grazing incidence from the rays.

For precision beam-splitters or output couplers, the thickness of the coating must be kept at very high tolerances to transmit the proper amount of light.

An optical wedge is the angle formed between two plane-surfaces (or between the principle planes of curved surfaces) due to manufacturing errors or limitations, causing one edge of the mirror to be slightly thicker than the other.

For second-surface or transmissive mirrors, wedges can have a prismatic effect on the light, deviating its trajectory or, to a very slight degree, its color, causing chromatic and other forms of aberration.

[52] In some applications, generally those that are cost-sensitive or that require great durability, such as for mounting in a prison cell, mirrors may be made from a single, bulk material such as polished metal.

Unlike with metals, the reflectivity of the individual dielectric-coatings is a function of Snell's law known as the Fresnel equations, determined by the difference in refractive index between layers.

Where viewing distances are relatively close or high precision is not a concern, wider tolerances can be used to make effective mirrors at affordable costs.

Optical discs are modified mirrors which encode binary data as a series of physical pits and lands on an inner layer between the metal backing and outer plastic surface.

Some devices use this to generate multiple reflections: Tradition states that Archimedes used a large array of mirrors to burn Roman ships during an attack on Syracuse.

It was however found that the mirrors made it very difficult for the passengers of the targeted boat to see; such a scenario could have impeded attackers and have provided the origin of the legend.

More recently, two skyscrapers designed by architect Rafael Viñoly, the Vdara in Las Vegas and 20 Fenchurch Street in London, have experienced unusual problems due to their concave curved-glass exteriors acting as respectively cylindrical and spherical reflectors for sunlight.

Mostly they were used as an accessory for personal hygiene but also as tokens of courtly love, made from ivory in the ivory-carving centers in Paris, Cologne and the Southern Netherlands.

For example, the famous Arnolfini Wedding by Jan van Eyck shows a constellation of objects that can be recognized as one which would allow a praying man to use them for his personal piety: the mirror surrounded by scenes of the Passion to reflect on it and on oneself, a rosary as a device in this process, the veiled and cushioned bench to use as a prie-dieu, and the abandoned shoes that point in the direction in which the praying man kneeled.