Modern Jewish historiography

[1] Though not many of their works fully survive, Hellenistic Jewish historians such as Artapanus of Alexandria and Eupolemus presented an interpretatio Judaica which argued for the antiquity of their people, drawing on inherited texts.

Moritz Steinschneider and Arnaldo Momigliano had observed that Jewish historiography appears to slow down at the end of the Second Temple period, and even Maimonides (1138–1204) considered history a waste of time.

[18] Some early attempts at writing history were met with controversy or imposed sanctions or prohibitions, such as bans, selective or general, or ordered burnings, or boycotts and effective sabotage of the publication's success.

[30] Spinoza and rabbi Joseph Solomon Delmedigo, who studied with Galileo, shared a goal to liberate science from theology, and combined it with scriptural references.

[32][33] Israël Salvator Révah, per Marina Rustow, has stressed that the anti-rabbinic themes expressed by both Uriel da Costa (1585-1640) and Spinoza had emerged from the crucible of Iberian crypto-Jewish culture.

[39] Jews of the medieval Islamic world such as Andalusia, North Africa, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq were prolific producers and consumers of historical works in Hebrew, Judeo-Arabic, Arabic and rarely Aramaic.

The Geniza is a storeroom in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat which contained scrap documents dating to the 9th century, and now exists at various academic institutions for study.

[85] The Languedoc region, which had a large population and respected rabbis known collectively as the Hachmei Provence, were forced to convert or flee in the 14th century, and they sought to avoid detection, which creates a paucity of documentation and a difficult scenario for historians.

This led to an estimated millions of texts destroyed in Spain and Portugal, especially centers of academic learning as Salamanca and Coimbra, rendering surviving manuscripts in foreign libraries rare and hard to come by.

Nofet Zufim drew on the classical theoretical writings of Cicero, Averroes and Quintilian[95] While not a work of history, it was a precursor to Azariah dei Rossi and cited by him as opening the door to the value of secular studies.

[97] The 1504 historic work of the Portuguese royal astronomer[98] Abraham Zacuto (1452-1515),[99][100] Sefer ha-Yuḥasin (Book of the Genealogies), contains anti-Christian historiographical polemic and urging of strength in the face of persecution and Jewish martyrdom.

He was necessarily a many-sided figure, for he lived and participated in the adventures of an explosive age, midway between medievalism and modernism, holding in its grasp the Inquisition and the discovery of new worlds.

[84][107] Solomon ibn Verga (1460-1554)'s 1520 Scepter of Judah (Shevet Yehudah) was a notable chronicle of Jewish persecutions, written in Italy and published in the Ottoman Empire in 1550.

[146] De Rossi's work was critical of the rabbinical establishment, questioning the historicity of post-biblical Jewish legends, and was met with condemnation, opprobrium and bans; Joseph Caro called for it to be burned, though he died before this was carried out, and Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen, the leader of the Venetian rabbis at the time, published herem prior to publication prohibiting owning or reading the book without permission.

[58] Despite its controversial status, Rossi's work was known in the 17th and 18th centuries, per David Cassel and Zunz as relayed by Joanna Weinberg, individuals such as Joseph Solomon Delmedigo and Menasseh ben Israel considered it required reading.

[22][163] While not as cutting-edge a historian as his contemporary, de Rossi, his books introduced historiography to the Ashkenazi audience, making him a forerunner of subsequent developments in Jewish culture.

[164] Abraham Portaleone was another Italian-Jewish Renaissance physician who, as discussed by Peter Miller and Moses Shulvass, published the historiographical work, Shilte ha-Giborim (Shields of the Heroes) in Mantua in 1612[165] which contained detailed descriptions of ancient life.

"[141][139][166][23] While ostensibly on the subject of the levitical tasks of the Temple, it touches on diverse topics such as botany, music, warfare, zoology, mineralogy, chemistry, and philology, and appears as a work of Renaissance scholarship per Samuel S.

[177] Nathan ben Moses Hannover's Yeven Mezulah (Abyss of Despair) (1653)[178][179][180][181] is a chronicle of the Khmelnytsky massacres or pogroms in eastern Europe in the mid 17th century.

[195] Isaac Euchel (1756-1804)'s Toledot Rabbenu Moshe ben Menahem (1788) was the first biography of Mendelssohn and significant in beginning a movement of biographical studies in Jewish historiography.

[231] Abraham Geiger founded the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums or school/seminary for Jewish studies, in Berlin in 1872, which remained until it was shuttered by the Nazis in 1942.

[233][234] Adolph Jellinek was a rabbi, publisher and pamphleteer who spoke and wrote emphatically against antisemitism, and republished medieval works from the Crusades era and history from the early modern period such as ha-Kohen's Emeq ha-Bakha.

[235] The Wissenschaft has been called "institutionalized German historicism," and a number of historians from Funkenstein to Meyer to Shmuel Feiner and Louise Hecht have challenged Yerushalmi's interpretation that the 19th century narrative is the salient shift in the characterization of Jewish historiography into modernity.

[243] Forerunners to Jewish national Zionist historiography from the 19th century include Peretz Smolenskin, Abraham Shalom Friedberg, and Saul Pinchas Rabinowitz, part of the Hibbat Zion movement, leading to Ahad Ha'am.

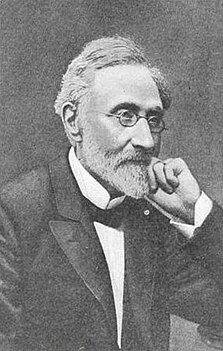

[278] Michael Brenner commented that Yerushalmi's "faith of fallen Jews" observation "is probably applicable to no one more than to Dubnow, who claimed to be praying in the temple of history that he himself erected.

[266] Esther Benbassa is another critic of the lachrymose conception and says that Baron is joined by Cecil Roth and to a lesser extent Schorsch in restoring a less tragic vision of Jewish fate.

[317] Yerushalmi deeply studied the Sephardim, such as Isaac Cardoso, particularly the marrano or converso, i.e. crypto-Jewish or forced Catholic secular Jews, which were a core historical interest.

The decline of Jewish collective memory in modern times is only a symptom of the unraveling of that common network of belief and praxis through whose mechanisms, some of which we have examined, the past was once made present.

[323] Myers writes that his teacher took the criticism of his paper, which contextualized the work as a post-Shoah malaise and a postmodern authorial perspective, hard, and did not know how to respond to it, leading to estrangement that lasted years before reconnecting shortly before his professor's death.

[329][43] Her 2008 work has changed the scholarly view of heresy with respect to the relative community interaction with the Karaites, a divergent group from the Rabbanite sect dominant in Judaism.