Historiography of gunpowder and gun transmission

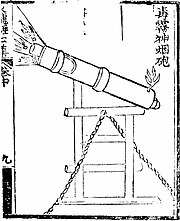

The earliest bronze guns found in China date back to the 13th century, with archaeological and textual evidence for previous nascent gunpowder technology developed beforehand.

However, historian Tonio Andrade notes that there is a surprising scarcity of reliable evidence of firearms in Iran or Central Asia prior to the late 14th century.

[2] One dissident opinion comes from Stephen Morillo, Jeremy Black, and Paul Lococo's War in World History which argues that "the sources are not entirely clear about Chinese use of gunpowder in guns.

Some consider him a mythical figure, used as a stand-in "for all the curious and ingenious experiments related to the new and dangerous mixture of saltpetre, sulfur (brimstone) and carbon.

J.R. Partington believes Schwartz is a purely legendary figure invented for the purpose of providing a German origin for gunpowder and cannon.

The chronological problem did not go unnoticed and in 1732, Hermann Boerhaave shifted the invention of gunpowder to Roger Bacon while Schwartz was relegated to the role of discovering its explosive military properties.

According to Juan de Mendoza, writing in 1585, the Chinese told the Portuguese that they had invented gunpowder, contradicting their own belief that "an Almane" had been the inventor.

[12] A deeply rooted misconception in the West holds that the Chinese never used gunpowder for war, that they employed one of the most potent inventions in the history of mankind for idle entertainment and children’s whizbangs.

These balls are ejected from a chamber … placed in front of a kindling fire of gunpowder; this happens by a strange property which attributes all actions to the power of the Creator.

"[18] The passage, dated to 1382, and its interpretation has been rejected as anachronistic by most historians, who urge caution regarding claims of Islamic firearms use in the 1204–1324 period as late medieval Arabic texts used the same word for gunpowder, naft, as they did for an earlier incendiary, naphtha.

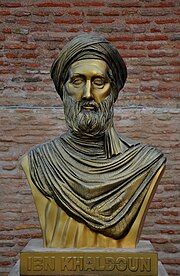

[21] Historian Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, based on his analysis of 14th-century Arabic manuscripts which he argues to be copies of earlier texts, claims that hand cannons were used at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.

[22] However Hassan's claims have been refuted by other historians such as David Ayalon, Iqtidar Alam Khan, Joseph Needham, Tonio Andrade, and Gabor Ágoston.

[25] However the term midfa, dated to textual sources from 1342 to 1352, cannot be proven to be true hand-guns or bombards, and contemporary accounts of a metal-barrel cannon in the Islamic world do not occur until 1365.

J. Dubois (1765-1848) maintained that rockets were invented in India as early as 300 BCE, on the grounds that the ancient Sanskrit classic, the Rāmāyaṇa, spoke of vāṇa or bāṇa, which was at one time thought to mean 'rocket'.

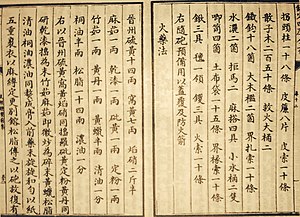

[32][17][33] The ingredients listed in Sukraniti as constituents for gunpowder such as realgar, opiment, lac, camphor, indigo, pine gum, magnetic oxide of iron, vermillion, graphite are used in the manufacture of incendiary weapons in Arthashastra and also appear in Chinese accounts.

[37][38] Authors such as A 7th century Chinese text mentions that people in northwest India were familiar with saltpetre and used it to produce purple flames.

The gun firing was probably shotless military pyrotechnic using tubular weapons (although Oppert states that another word 'Nadika'' is also used in one of the text's version and may well mean gongs).

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi mentions in a treaties dated 910 a material called 'Indian salt', which he describes as "black and friable, with very little glitter,"[41] which has been interpreted as saltpetre by Berthelot but this is disputed by Joseph Needham.

[41] According to Firishta, Mehmud Ghaznavi (r. 999–1030) employed 1,008 cannon (top) and muskets (tufang) during his battle of Peshawar with Kabul Shahi king Annandapal.

This difficulty must not be allowed to impair the interest or value of Indian works, but they must also be examined from the point of view of their scientific and technical contents with due care and with a suitably critical attitude.

Rajendralala Mitra raised doubts about the age of another work by Usanas, Nitisara of Sukracharya, noting that it contains descriptions of firearms as they were a hundred years ago.

Ray pointed out that the gunpowder mixture of 4:1:1 saltpetre, charcoal, and sulphur found in Sukraniti was the most efficient for guns and was not known in Europe until the 16th century, leading him to believe that the content was an interpolation by "the handiwork of some charlatan.

Gode provided textual evidence that pyrotechnical recipes recorded in the Sanskrit treatise, Kautukacintamani, were copied from a Chinese source.

[51] The theory of Indian origin of gunpowder has been utilized by the Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party to oppose all attempts to ban bursting of firecrackers by Hindus in Diwali.

In contrast gunpowder formulas in Europe appear both later and offer very little divergence from the already ideal proportions for the purpose of creating an explosive and propellant powder.

"[14] Perhaps even further in the Sinocentric gun transmission camp is Joseph Needham who claims that "all the long preparations and tentative experiments were made in China, and everything came to Islam and the West fully fledged, whether it was the fire-lance or the explosive bomb, the rocket or the metal-barrel hand-gun and bombard.

The rapid spread of guns across Eurasia, only 50 years from China to Europe, with non-existent evidence of its route from one extreme of the continent to the other, remains a mystery.

Other Chinese inventions such as the compass, paper, and printing took centuries to reach Europe, with events such as the Battle of Talas as perhaps a possible takeoff point for discussion.

"[54] According to Kate Raphael, the list of Chinese specialists recruited by Genghis Khan and Hulagu provided by the History of Yuan includes only carpenters and blacksmiths, but no gunpowder workers.

Some historians have claimed the Mongols used gunpowder weapons, essentially bombs hurled by catapults, in the Middle East and perhaps Eastern Europe; unfortunately there is no definite documentary or archaeological evidence to confirm it.