Monetary reform in the Soviet Union, 1922–24

The principal objectives of the reform included stopping the effects of hyperinflation, establishing a unified medium of exchange and the creation of a more-independent central bank.

[1] According to economic data recorded in the archives of the Soviet Union[2] and the Russian Federation, results of the reform were mixed; some modern-day economists call the new policies a successful transition towards state capitalism, but others describe them as problematic and failing to uphold the targets laid out in its original blueprint.

According to historian Paul Flewers, economic war communism and ideological questioning of the long-term need for a monetary system triggered a massive increase in the money supply; this prolonged a continued rise in the Soviet Union's domestic inflation rate.

A more-independent central bank became an economic oversight mechanism to fight inflation and gave the Soviet economy the flexibility to counter domestic and global fluctuations.

[8] Economist Amy Hewes wrote that the policy outcomes were the Soviet economy's return to the gold standard, the introduction of a separate national currency, elimination of the government’s budget deficit and the restoration of a centrally-administered tax system.

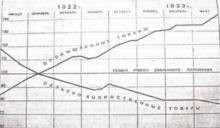

By the end of 1922, a dual-currency system was in place; gold-pegged Russian chervonets were restored as a unit of account, and Soviet printed money (sovznaks) was commissioned as the nationalised medium of exchange and domestic means of payment.

Strumilin remained supportive of a "socialist commodity exchange,"[This quote needs a citation] which functioned under the rules of modern-day fiat currency-backed monetary systems.

[5] According to Katzenellenbaum’s data,[9] the Soviet trade surplus grew steadily under the dual-currency system and generated the capital reserve needed to repay the short-term foreign loans which backed the chervonets.

All primary debt was repaid and the national current account became positive by the end of 1923, indicating that the Soviet Union had control of its monetary system.

[10] Although the sovznak-oriented Soviet population found it more difficult to conduct daily transactions, chervonets-dominated government expenditures had no shortage of funds and the national balance sheet remained cash-flow positive; state enterprises had minimal losses or profited.

[6] The Soviet Union’s currency circulation was optimised and the chervonets (later defined as the rouble) was again pegged to gold, the universal storage of value before the adoption of the Bretton Woods system.