Mongol invasion of Europe

Melik, one of the princes from the Ögedei family who participated in the expedition, invaded the Transylvania region of the Hungarian kingdom, called Sasutsi in sources.

[2] In 1223, Mongols routed a near 50,000 army of Kievan Rus' at the Battle of the Kalka River, near modern-day Mariupol[citation needed], before turning back for nearly a decade.

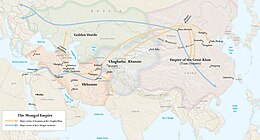

Batu Khan, son of Jochi, was the overall leader, but Subutai was the strategist and commander in the field, and as such, was present in both the northern and southern campaigns against Rus' principalities.

While Kadan's northern force won the Battle of Legnica and Güyük's army triumphed in Transylvania, Subutai was waiting for them on the Hungarian plain.

The newly reunited army then withdrew to the Sajó river where they inflicted a decisive defeat on King Béla IV of Hungary at the Battle of Mohi.

One army defeated an alliance which included forces from fragmented Poland and their allies, led by Henry II the Pious, Duke of Silesia in the Battle of Legnica.

[13][14] A small force of Mongolians did attack the strategically located (on the way to the mountain passes) Bohemian town of Kladsko (Kłodzko) but Wenceslaus' cavalry managed to fend them off.

[20] After these failed attempts, Baidar and Kadan continued raiding Moravia (via the Moravian Gate route into the valley of the river Morava towards the Danube) before finally going southward to reunite with Batu and Subutai in Hungary.

Still, tens of thousands avoided Mongol domination by taking refuge behind the walls of the few existing fortresses or by hiding in the forests or large marshes along the rivers.

The Mongols, instead of leaving the defenseless and helpless people and continuing their campaign through Pannonia to Western Europe, spent time securing and pacifying the occupied territories.

[22] During the winter, contrary to the traditional strategy of nomadic armies which started campaigns only in spring-time, they crossed the Danube and continued their systematic occupation, including Pannonia.

Rogerius of Apulia, an Italian monk and chronicler who witnessed and survived the invasion, pointed out not only the genocidal element of the occupation, but also that the Mongols especially "found pleasure" in humiliating local women.

[24] But while the Mongols claimed control of Hungary, they could not occupy fortified cities such as Fehérvár, Veszprém, Tihany, Győr, Pannonhalma, Moson, Sopron, Vasvár, Újhely, Zala, Léka, Pozsony, Nyitra, Komárom, Fülek and Abaújvár.

[31] In preparation for a second invasion, Gradec was granted a royal charter or Golden Bull of 1242 by King Béla IV, after which citizens of Zagreb engaged in building defensive walls and towers around their settlement.

Using similar tactics during their campaigns in previous Eastern and Central European countries, the Mongols first launched small squadrons to attack isolated settlements in the outskirts of Vienna in an attempt to instill fear and panic among the populace.

Unlike in Hungary however, Vienna under the leadership of Duke Frederick and his knights, together with their foreign allies, managed to rally quicker and annihilate the small Mongolian squadron.

Feudal Europe was saved from sharing the fate of China and the Grand Duchy of Moscow not by its tactical prowess but by the unexpected death of the Mongols' supreme ruler, Ögedei, and the subsequent eastward retreat of his armies.

[49] In the decades following the Mongolian raids on European settlements, Western armies (particularly Hungary) started to adapt to the Mongol tactics by building better fortifications against siege weapons and improving their heavy cavalry.

[53][54] Several sources mention the Mongols deploying firearms and gunpowder weapons against European forces at the Battle of Mohi in various forms, including bombs hurled via catapult.

Those conditions would have been less than ideal for the nomadic Mongol cavalry and their encampments, reducing their mobility and pastureland, curtailing their invasion into Europe west of the Hungarian plain,[64] and hastening their retreat.

Finally, they were stretched thin in the European theater, and were experiencing a rebellion by the Cumans (Batu returned to put it down, and spent roughly a year doing so).

[69] He had made the new Rus' conquests secure for the years to come, and when the Great Khan died and Batu rushed back to Mongolia to put in his claim for power, it ended his westward expansion.

The Mongol Empire was ruled by a regency under Ögedei's widow Töregene Khatun, whose only goal was to secure the Great Khanate for her son, Güyük.

Batu also had problems in his last years with the Principality of Halych-Volhynia, whose ruler, Danylo of Halych, adopted a policy of confronting the Golden Horde and defeated some Mongol assaults in 1254.

His son did not live long enough to implement his father and Subutai's plan to invade Europe, and with his death, Batu's younger brother Berke became Khan of the Kipchak Khanate.

Meanwhile, Emperor Frederick II, a well-educated ruler, wanted to annex Italy to unite his separated kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire and Sicily.

In addition to calling a council to depose the Holy Roman Emperor, Pope Gregory IX and his successor Innocent IV excommunicated Frederick four times and labeled him the Antichrist.

[72] The Golden Horde raids in the 1280s (those in Bulgaria, Hungary, and Poland), were much greater in scale than anything since the 1241–1242 invasion, thanks to the lack of civil war in the Mongol Empire at the time.

The outcome could not have contrasted more sharply with the 1241 invasion, mostly due to the reforms of Béla IV, which included advances in military tactics and, most importantly, the widespread building of stone castles, both responses to the defeat of the Hungarian Kingdom in 1241.

The failed Mongol attack on Hungary greatly reduced the Golden Horde's military power and caused them to stop disputing Hungarian borders.