Mongol invasions of Vietnam

The campaigns are treated by a number of scholars as a success due to the establishment of tributary relations with Đại Việt despite the Mongols suffering major military defeats.

By the end of the second and third invasions, which involved both initial successes and eventual major defeats for the Mongols, both Đại Việt and Champa decided to accept the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty and became tributary states to avoid further conflict.

[22] To avoid a costly frontal assault on the Song, which would have required a risky forced crossing of the lower Yangtze, Möngke decided to establish a base of operations in southwestern China, from which a flank attack could be staged.

[27] Duan Xingzhi fled to Shanchan (modern-day Kunming) and continued to resist the Mongols with aid from local clans until autumn 1255 when he was finally captured.

[28] Bin Yang noted that the Duan clan was recruited to assist with further invasions of the Burmese Pagan Empire and the initial successful attack on the Vietnamese kingdom of Đại Việt.

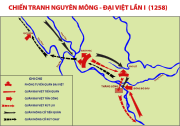

[29] Trần Thái Tông opposed the encroachment of a foreign army across his territory to attack their ally, therefore the envoys were imprisoned,[30] and soldiers on elephants were prepared to deter the Mongol troops.

[34][31] The Vietnamese senior leaders were able to escape on pre-prepared boats, while part of their army was destroyed at No Nguyen (modern Việt Trì on the Red River).

Via Đại Việt, he launched a new assault on the Song in the summer of 1259, moving into Guilin and reaching as far as Tanzhou (in modern-day Hunan Province) in a joint offensive led by Möngke.

[44] The position of Historian Geoff Wade is that they would be able to gain access to commodities from the states across the Indian Ocean through Arab and Persian merchants managing trade from Champa.

[48] Thus, in the summer of 1282, when Yuan envoys He Zizhi, Hangfu Jie, Yu Yongxian, and Yilan passed through Champa, they were detained and imprisoned by the Cham Prince Harijit.

[10] The aged Champa king Indravarman V abandoned his temporary headquarters in the palace, and set fire to his warehouses and retreated out of the capital, avoiding Mongol attempts to capture him in the hills.

[10] From a captured spy, Sogetu knew that Indravarman had 20,000 men with him in the mountains; he had summoned Cham reinforcements from Panduranga (Phan Rang) in the south, and also dispatched emissaries to Đại Việt, the Khmer Empire and Java to seek aid.

[52] In 1261, Kublai enfeoffed Trần Thánh Tông as "King of Annam" (Annan guowang) and began operating a nominal darughachi (tax collector) in Dai Viet.

[40] He sent his son Hugaci to the Vietnamese court with a list of demands,[55] such as both monarchs submitting in person, censuses, taxes in both money and labor, incense, gold, silver, cinnabar, agarwood, sandalwood, ivory, tortoiseshell, pearls, rhinoceros horn, silk floss, and porcelain cups – requirements that neither of the two kingdoms had met.

Toghon demanded that the Vietnamese allow his passage to Champa, in order to attack the Cham army from both north and south, but they refused, and concluded that this was the pretext for a Yuan conquest of Đại Việt.

[60] Southern Song Chinese military officers and civilian officials who had intermarried with the Vietnamese ruling elite then went to serve the government in Champa, as recorded by Zheng Sixiao.

[63] Also in the same year, the Venetian traveler Marco Polo almost certainly visited Đại Việt[d] (Caugigu)[e][c] almost when the Yuan and the Vietnamese were ready for war,[c] then he went to Chengdu via Heni (Amu).

[11] Toghon sent an officer name Tanggudai to instruct Sogetu, who was in Huế, to march north in a pincer movement while at the same time sending frantic appeals for reinforcements from China, and wrote to the Vietnamese king that the Yuan forces had come in, not as enemies but as allies against Champa.

[81] Due to a lack of food supplies, Toghon and Omar's army retreated from Thăng Long to their fortified main base in Vạn Kiếp northeast of Hanoi on 5 March 1288.

[79] An account of the battle by Lê Tắc, a Vietnamese scholar who defected to the Yuan in 1285, said that the remnants of the army followed him north in retreat and reached Yuan-controlled territory on the Lunar New Year's Day in 1289.

[79] After the war Lê Tắc got permanently exiled in China, and was appointed by the Yuan government to the position of Prefect of Pacified Siam (Tongzhi Anxianzhou).

[89] Kublai, angry over the Yuan defeats in Đại Việt, banished prince Toghon to Yangzhou[90] and wanted to launch another invasion, but was persuaded in 1291 to send Minister of Rites Zhang Lidao to induce Trần Nhân Tông to come to China.

[92] He wrote a letter to Kublai Khan describing the death and destruction the Mongol armies had wrought, vividly recounting the brutality of the soldiers and the desecration of sacred Buddhist sites.

In 1289, Đại Việt released most of the Mongol prisoners of war to China, but Omar, whose return Kublai particularly demanded, was intentionally drowned when the boat transporting him was contrived to sink.

[81] In the winter of 1289–1290, King Trần Nhân Tông led an attack into modern-day Laos, against the advice of his advisors, with the goal of preventing raids from the inhabitants of the highlands.

There were no records of what caused the crop failures, but possible factors included neglect of the water control system due to the war, the mobilization of men away from the rice fields, and floods or drought.

[95] Although Đại Việt repelled the Yuan, the capital Thăng Long was razed, many Buddhist sites were decimated, and the Vietnamese suffered major losses in population and property.

Kublai's successor Temür Khan (r.1294-1307), later released all detained envoys and resumed their tributary relationship initially established after the first invasion, which continued to the end of the Yuan.

[70] In 1305, Cham King Chế Mân (r. 1288 – 1307) married the Vietnamese princess Huyền Trân (daughter of Trần Nhân Tông) as he ceded two provinces Ô and Lý to Đại Việt.

[98][99] Despite the military defeats suffered during the campaigns, they are often treated as a success by historians for the Mongols due to the establishment of tributary relations with Đại Việt and Champa.