Mongolia under Qing rule

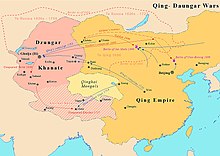

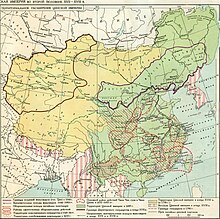

However, the Khalkha Mongols in Outer Mongolia continued to rule until they were overrun by the Dzungar Khanate in 1690, and they submitted to the Qing dynasty in 1691.

Even before the dynasty began to take control of China proper in 1644, the escapades of Ligden Khan had driven a number of Mongol tribes to ally with the Later Jin.

[4][5] After Ligden's defeat and death his son had to submit to the Later Jin, and when the Qing dynasty was founded the following year, most of what is now called Inner Mongolia already belonged to the new state.

After conquering the Ming, the Qing identified their state as Zhongguo (中國, the term for "China" in modern Chinese), and referred to it as "Dulimbai Gurun" in the Manchu language.

When the Qing conquered Dzungaria in 1759, they proclaimed that the new land which formerly belonged to the Dzungar Mongols was now absorbed into "China" (Dulimbai Gurun) in a Manchu language memorial.

[9] The Manchu language version of the Convention of Kyakhta (1768), a treaty with the Russian Empire concerning criminal jurisdiction over bandits, referred to people from the Qing as "people from the Central Kingdom (Dulimbai Gurun)",[10][11][12][13] and the usage of "Chinese" (Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) in the convention certainly referred to the Mongols.

"[17] As Nurhaci formally declared independence from the Ming dynasty and proclaimed the Later Jin in 1616, he gave himself a Mongolian-style title, consolidating his claim to the Mongolian traditions of leadership.

After Abunai showed disaffection with Manchu Qing rule, he was placed under house arrested in 1669 in Shenyang and the Kangxi Emperor gave his title to his son Borni.

The three khans of Khalkha in Outer Mongolia had established close ties with the Qing dynasty since the reign of Hong Taiji, but had remained effectively self-governing.

[18] The Oirat Khoshut Upper Mongols in Qinghai rebelled against the Qing during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor but were crushed and defeated.

Once brought under Qing control, the traditional clan structures of Inner and Outer Mongolia were replaced with the Manchu Banner system.

[19] This new administrative structure had drastic consequences for Mongolian culture, as the leader (Jasagh) of each banner was chosen by Qing authorities, although existing Mongol princes were often picked for the position.

Doing so would result in serious punishment, thereby keeping the Mongol clans isolated and disconnected, preventing the formation of united Khanate and maintaining Qing control in these regions.

[21] Mongol pilgrims wanting to leave their banner's borders for religious reasons such as pilgrimage had to apply for passports to give them permission.

Accordingly, in 1791, the Qing government was petitioned by the Mongol prince of the Ghorlos Front Banner to legalize the Han settlers in the area.

By 1638 it had been renamed to Lifan Yuan, though it is sometimes translated in English as the "Court of Colonial Affairs" or the "Board for the Administration of Outlying Regions".

Originally as "privileged subjects", the Mongols were obligated to assist the Qing court in conquest and suppression of rebellion throughout the empire.

Indeed, during much of the dynasty the Qing military power structure drew heavily on Mongol forces to police and expand the empire.

In acknowledgement of their subordination to the Qing dynasty, the banner princes annually presented tributes consisting of specified items to the Emperor.

Apart from China's industrial and technical advantage over the steppe, three main factors combined to reinforce the decline of the Mongol's once-glorious military power and the decay of the nomadic economy.

For example, the widely-respected Shu Han General known for his loyalty during the Three Kingdom period [220 A.D. to 280 A.D.] Guan Yu, the Guandi, was equated with a figure which had long been identified with the Tibetan and Mongolian folk hero Geser Khan.

Previously Mongolia had little internal trade other than non-market exchanges on a relatively limited scale, and there was no Mongolian merchant class.

The monasteries greatly aided the Han Chinese merchants to establish their commercial control throughout Mongolia and provided them with direct access to the steppe.

Nevertheless, the empire did make various attempts to restrict the activities of these Han merchants such as the implementation of annual licensing, because it had been the Qing policy to keep the Mongols as a military reservoir, and it was considered that the Han Chinese trade penetration would undermine this objective, although in many cases such attempts had little effects.

At the same time, as the ruling Manchus had become increasingly sinicized and population pressure in China proper emerged, the dynasty began to abandon its earlier attempts to block Han Chinese trade penetration and settlement in the steppe.

After all, Han Chinese economic penetration served the dynasty's interests, because it not only provided support of the government's Mongolian administrative apparatus, but also bound the Mongols more tightly to the rest of empire.

Even during the 18th century growing number of Han settlers had already illegally begun to move into the Inner Mongolian steppe and to lease land from monasteries and banner princes, slowing diminishing the grazing areas for the Mongols' livestock.

The monasteries had taken over substantial grazing lands, and monasteries, merchants and banner princes had leased many pasture lands to Han Chinese as farmland, although there was also popular resentment against oppressive taxation, Han settlement, shrinkage of pasture, as well as debts and abuse of the banner princes' authority.

Many impoverished Mongols also began to take up farming in the steppe, renting farmlands from their banner princes or from Han merchant landlords who had acquired them for agriculture as settlement for debts.

Anyway, the Qing attitude towards Han Chinese colonization of Mongolian lands grew more and more favorable under pressure of events, particularly after the Amur Annexation by Russia in 1860.