Northern Yuan

The Northern Yuan (Chinese: 北元; pinyin: Běi Yuán) was a dynastic state ruled by the Mongol Borjigin clan based in the Mongolian Plateau.

[4] Despite this decentralization, a remarkable concord continued within the Dayan Khanid aristocracy, and intra-Chinggisid civil war remained unknown until the reign of Ligdan Khan (1604–1634),[5] who saw much of his power weakened in his quarrels with the Mongol tribes and was defeated by the Later Jin dynasty.

The historiographical name "Northern Yuan" first appeared in the Korean historical text Goryeosa written in Classical Chinese.

[9][11] In English, the term "Northern Yuan (dynasty)" is generally used to cover the entire period from 1368 to 1635 for historiographical purpose.

[18] In 1351, the Red Turban Rebellion erupted in the Huai River valley, which saw the rise of Zhu Yuanzhang, a Han peasant, who eventually established the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) in southern China.

[19] Toghon Temür (r. 1333–1370), the last ruler of the Yuan, fled north to Shangdu (located in present-day Inner Mongolia) from Dadu upon the approach of Ming forces.

The Ming army pursued the Yuan remnants into the Mongolian steppe in 1372 but was defeated by Biligtü Khan Ayushiridara (r. 1370–1378) and his general Köke Temür (d. 1375).

In 1387, the Ming defeated the Uriankhai Mongols, and in the following year they achieved decisive victory around the Buir Lake against Uskhal Khan Tögüs Temür.

[23] The Genghisid (Major descendants of Kublai[24]) rulers of the Northern Yuan also buttressed their claim on China,[25][26] and held tenaciously to the title of Emperor (or Great Khan) of the Great Yuan (Dai Yuwan Khaan, or 大元可汗)[27] to resist the Ming who had by this time become the real ruler in China proper.

According to the traditional Chinese political orthodoxy, there could be only one legitimate dynasty whose rulers were blessed by Heaven to rule as Emperor of China (see Mandate of Heaven), so the Ming also denied the Yuan remnants' legitimacy as emperors of China, although the Ming did consider the previous Yuan which it had succeeded to be a legitimate dynasty.

In 1388, the Mongol throne was taken over by Jorightu Khan Yesüder, a descendant of Arik Böke (Tolui's son), with the support of the Oirats.

[31] The following century saw a succession of Genghisid rulers, many of whom were mere figureheads put on the throne by those warlords who happened to be the most powerful.

The Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424) issued Öljei Temür an ultimatum demanding his acceptance of tributary relations to the Ming dynasty.

After the death of Öljei Temur, the Oirats under their leader Bahamu (Mahmud) (d. 1417) enthroned an Ariq Bökid Delbeg Khan in 1412.

[38] From Esen's death to 1481 different warlords of the Kharchin, the Belguteids and Ordos Mongols fought over succession and had their Genghisid khans enthroned.

Manduulun's young khatun Mandukhai proclaimed a seven-year-old boy named Batumongke of Genghisid descent as khan.

Dayan Khan finally defeated the southwestern Mongols in 1510 with the assistance of his allies, Unebolad wang and the Four Oirats.

As a result, the Tümed Mongols ruled in the Ordos region and they gradually extended their domain into northeastern Qinghai.

[45] At the apogee of Dayan's reign, the Northern Yuan stretched from the Siberian tundra and Lake Baikal in the north, across the Gobi, to the edge of the Yellow River and south of it into the Ordos.

The tümens functioned both as military units and as tribal administrative bodies who hoped to receive taijis, descended from Dayan Khan.

[49] A series of smallpox epidemics and lack of trade forced the Mongols to repeatedly plunder the districts of China.

Jasagtu appointed a Tibetan Buddhist chaplain of the Karmapa order and agreed that Buddhism would henceforth become the state religion of Mongolia.

In 1577, Altan and Sechen received the 3rd Dalai Lama, which started the conversion of Tumed and Ordos Mongols to Buddhism.

Ligdan built a new capital in Chahar land known as Chaghan Baishin (White House) and promoted the building of Buddhist monasteries, translation of Tibetan literature, and trade with the Ming dynasty.

Although sharing many similar characteristics with the Mongols, the Jurchens were not nomads, but tribal people who had adopted Chinese agricultural practices.

In the following year, Uuba Noyan of the Khorchin had his younger brother marry one of Nurhaci's daughters, cementing the alliance.

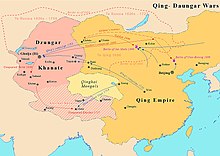

To avenge the death of his brother, Galdan established friendly relations with the Russians who were already at war with Chikhundorj over territories near Lake Baikal.

Armed with Russian firearms, Galdan led 30,000 Dzungar troops into Outer Mongolia in 1688 and defeated Chikhundorj in three days.

After two bloody battles with the Dzungars near Erdene Zuu Monastery and Tomor, Chikhundorji and his brother Jebtsundamba Khutuktu Zanabazar fled across the Gobi Desert to the Qing dynasty and submitted to the Kangxi Emperor.

This expansion of the Dzungar state was viewed with worry by the Qing, which led the Kangxi Emperor (Enh-Amgalan khaan-in Mongolian) to block Galdan.