Moon illusion

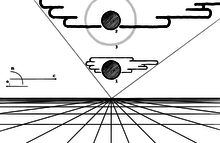

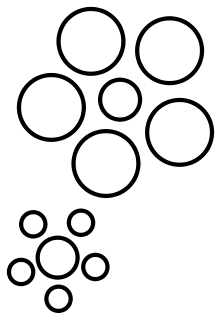

A simple way of demonstrating that the effect is an illusion is to hold a small pebble (say, 0.33 inches or 8.4 millimetres wide) at arm's length (25 inches or 64 centimetres) with one eye closed, positioning the pebble so that it covers (eclipses) the full Moon when high in the night sky.

[3] After reviewing the many different explanations in their 2002 book The Mystery of the Moon Illusion, Ross and Plug conclude "No single theory has emerged victorious.

[9] Similarly Cleomedes (about 200 A.D.), in his book on astronomy, ascribed the illusion both to refraction and to changes in apparent distance.

Through additional works (by Roger Bacon, John Pecham, Witelo, and others) based on Ibn al-Haytham's explanation, the Moon illusion came to be accepted as a psychological phenomenon in the 17th century.

"[13] The brain is accustomed to seeing terrestrially-sized objects in a horizontal direction and also as they are affected by atmospheric perspective, according to Schopenhauer.

If the Moon is perceived to be in the general vicinity of the other things seen in the sky, it would be expected to also recede as it approaches the horizon, which should result in a smaller retinal image.

But since its retinal image is approximately the same size whether it is near the horizon or not, the brain, attempting to compensate for perspective, assumes that a low Moon must be physically larger.

Experiments by many other researchers have found the same result; namely, when pictorial cues to a great distance are subtracted from the vista of the large-looking horizon Moon it looks smaller.

A potential problem for the apparent distance theory has been that few people (perhaps about 5%) perceive the horizon Moon as being both larger and further away.

This is reinforced by the idea that the brain does not consciously perceive distance and size, as spatial awareness is a subconscious, retino cortical cognition.

Wade[1] shortly summarizes historical references to the moon illusion starting with Aristotle; he lists quotes by Aristotle (~330 BC), Ptolemy (~142, 150), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) (1083), John Pecham (~1280), Leonardo da Vinci (~1500), René Descartes (1637), Benedetto Castelli (1639), Pierre Gassendi (1642), Thomas Hobbes (1655), J. Rohault (1671), Nicolas Malebranche (1674), William Molyneux (1687), J. Wallis (1687), George Berkeley (1709), J.T.