Moot hill

Although the word moot or mote is of Old English origin, deriving from the verb to meet, it has come to have a wider meaning throughout the United Kingdom; initially referring to any popular gathering.

In England, the word folkmoot in time came to mean a more specific local assembly with recognised legal rights.

[3] Many other names are used for prominent earthworks, depending to some extent on their location within the United Kingdom, and some of them are known to have served as moot hills at some point in their existence.

(In this fortification, a wooden or stone keep was built atop a small mound, usually man-made, which was in turn surrounded by a ditch and an outer ward called the "bailey".)

One common aid to identification is size: most moot hills, in addition to lacking signs of defensive walls and ditches, are smaller than most mottes.

The term (also Couthil or Cuthil) is found as a placename element at over sixty sites and many are associated with medieval shires or thanages.

[6] Francis Grose in 1797 published his 'Antiquities of Scotland', and going from the 1789 date of the numerous engravings this was a little over forty years from the abolition of this aspect of the feudal system.

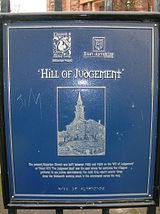

[7] He goes on to say – In ancient times, courts for the administration of justice were generally held in the open fields, and judgement was both given and executed in the same place; in every earldom, and almost every barony and jurisdiction of any considerable extent, there was a particular place allotted for that purpose; it was generally a small eminence, either natural or artificial, near the principal Mansion-house and was called the mote hill, or in Latin, mons placiti.

In that place all the vassals of the jurisdiction were obliged to appear at iwdain times; and the superior gave judgement in such cases as fell within the powers committed to him by law or custom; in the same spot too, the gallows was erected for the execution of capital offenders; hence these places commonly go by the name of the Gallows Knoll; near the royal palaces there was usually a mote hill, where all the freeholders of the kingdom met together, both to transact public offices, and to do homage to their sovereign, who was seated on the top of the eminence.

It is highly probable the Hurly Heaky (named after the sport of sliding down a slope on a trough or sledge; tobogganing) was the mote hill of the Castle of Sterling, or perhaps of a much larger jurisdiction.

[9] It is known that in Scotland, Brehons or Judges administered justice from 'Court Hills', especially in the highlands, where they were called a tomemoid (from Scots Gaelic tom a' mhòid) – that is, the Court Hillock.

In ancient times suitable buildings would rarely have existed and there was usually no alternative other than to use an outdoor gathering place.

[11] The moot hills' part in the practice of law derives from the introduction of feudalism by the Normans in England or in Scotland by the Scottish kings such as David I 1125–1153 who introduced feudalism and delegated very extensive jurisdiction over large areas of land to men like the Walter the Steward (Renfrew & the northern half of Kyle) or de Morville (Cunningham) and they in turn delegated quite extensive powers to their own vassals.

These invitees, largely of Norman, Fleming and Breton origin were, under feudal charter, given significant grants of land, were invited and did not come as conquerors as had been the case in England.

Within a few generations, regular intermarriage and the Wars of Independence had removed most of the differences between native and incomer, although not those between Highlander and Lowlander.

[12] Burgh courts were held in the open air, round the market cross, a standing stone, a moot hill or a prominent tree.

Some crimes were reserved for royal courts, namely murder, rape, robbery with violence, fire raising and treason.

Sir John Skene in his glossary of Scots legal terms defines it as In this Realme he is called ane Barrone quha haldis his landes immediatlie in chiefe of the King and hes power of pit and gallow.

[18] The baron and the baron baillie, his deputy, and the council, were concerned with such matters as: responsibility for repair to ditches and hedges, assessment of damage caused by cattle found on another's ground, under thirlage laws, the maintenance of the mill race in good order and free from weeds and the mending of the mill dam.

[16][17] It was enacted at the parliament assembled in Forfar in 1057 by King Malcolm Canmore that every baron should erect a gibbet (gallows) for the execution of male criminals, and sink a well or pit, for the drowning of females.

[14] It is not clear why men were more likely to be hanged and women drowned in a fen, river, pit or 'murder hole'; however, it may relate to ideas of decency.

[25][26] At Cumnock in East Ayrshire, women were placed in a sack and the mouth was tied;[27] in other cases the condemned had to walk down a ladder that was then withdrawn.

The furca was a device of punishment in ancient Rome and refers to the gallows for hanging men; the fossa was a pit for the drowning of women.

As previously stated, the hereditary right of high justice survived until 1747, when it was removed from the barons and from the holders of regalities and sheriffdoms, by the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746.

They had many ways of making money for themselves, such as (1) the bailie's darak, as it was called, or a day's labour in the year from every tenant on the estate; (2) confiscations, as they generally seized on all the goods and effects of such as suffered capitally; (3) all fines for killing game, blackfish, or cutting green wood were laid on by themselves, and went into their own pockets.

[32] At Greenhills near Barrmill in North Ayrshire a different method is said to have been employed, namely that of raising a flag at the Bore stone; a prominent site near the moot hill.

[35] In mediaeval law the barony required a principal residence at which the legal process could be formally transacted, which explains why many such motes as that at Ellon were retained, here by the earls of Buchan, when little else remained of their possessions in the district.

[40] In Scotland feudalism and its bonds of allegiance to the local laird was associated with the Jacobite risings with the result that the Hanoverian Government took steps to undermine the system.

After 1747 the moot hill was not used as a part of the baronial court process and the requirement for a gathering place for soldiers was also a thing of the past.

Moot hills gradually ceased to have any significant role and many have suffered the final ignomy of being ploughed out and their existence almost or actually forgotten.