Morphological typology

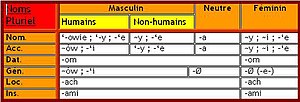

Agglutinative languages rely primarily on discrete particles (prefixes, suffixes, and infixes) for inflection, while fusional languages "fuse" inflectional categories together, often allowing one word ending to contain several categories, such that the original root can be difficult to extract.

[citation needed] Analytic languages show a low ratio of morphemes to words; in fact, the correspondence is nearly one-to-one.

Note that the ideographic writing systems of these languages play a strong role in regimenting linguistic continuity according to an analytic, or isolating, morphology (cf.

Not all analytic languages are isolating; for example, Chinese and English possess many compound words, but contain few inflections for them.

In addition, there tends to be a high degree of concordance (agreement, or cross-reference between different parts of the sentence).

For example, Navajo is sometimes categorized as a fusional language because its complex system of verbal affixes has become condensed and irregular enough that discerning individual morphemes is rarely possible.

Agglutinative languages include Hungarian, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Turkish, Mongolian, Korean, Japanese, Swahili, Zulu and Indonesian.

[citation needed] However, it is a common misconception that polysynthetic morphology is universal among Amerindian languages.

Benjamin Whorf categorized Nahuatl and Blackfoot as oligosynthetic, but most linguists disagree with this classification and instead label them polysynthetic or simply agglutinative.

[5] Other languages inspired by Esperanto like Ido and Novial also tend to be agglutinative, although some examples like Interlingua might be considered more fusional.

[6] Among engineered languages, Toki Pona is completely analytic, as it contains only a limited set of words with no inflections or compounds.

[8] While the above scheme of analytic, fusional, and agglutinative languages dominated linguistics for many years—at least since the 1920s—it has fallen out of favor more recently.

Jennifer Garland of the University of California, Santa Barbara gives Sinhala as an example of a language that demonstrates the flaws in the traditional scheme: she argues that while its affixes, clitics, and postpositions would normally be considered markers of agglutination, they are too closely intertwined to the root, yet classifying the language as primarily fusional, as it usually is, is also unsatisfying.

Dixon cites the Egyptian language as one that has undergone the entire cycle in three thousand years.

For instance, Elly van Gelderen sees the regular patterns of linguistic change as a cycle.

WALS lists these variables as: These categories allow to capture non-traditional distributions of typological traits.

For example, high exponence for nouns (e.g., case + number) is typically thought of as a trait of fusional languages.