Old Chinese

The latter part of the Zhou period saw a flowering of literature, including classical works such as the Analects, the Mencius, and the Zuo Zhuan.

In addition, the rhymes of the earliest recorded poems, primarily those of the Classic of Poetry, provide an extensive source of phonological information with respect to syllable finals for the Central Plains dialects during the Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn periods.

[4] Like modern Chinese, it appears to be uninflected, though a pronoun case and number system seems to have existed during the Shang and early Zhou but was already in the process of disappearing by the Classical period.

In addition, many of the smaller languages are poorly described because they are spoken in mountainous areas that are difficult to reach, including several sensitive border zones.

[38][39] Initial consonants generally correspond regarding place and manner of articulation, but voicing and aspiration are much less regular, and prefixal elements vary widely between languages.

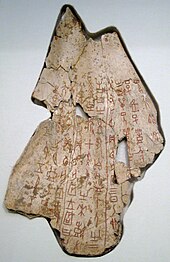

[45] The earliest known written records of the Chinese language were found at the Yinxu site near modern Anyang identified as the last capital of the Shang dynasty, and date from about 1250 BC.

The language written is undoubtedly an early form of Chinese, but is difficult to interpret due to the limited subject matter and high proportion of proper names.

[47] From early in the Western Zhou period, around 1000 BC, the most important recovered texts are bronze inscriptions, many of considerable length.

The oldest sections of the Book of Documents, the Classic of Poetry and the I Ching, also date from the early Zhou period, and closely resemble the bronze inscriptions in vocabulary, syntax, and style.

Although these are perishable materials, a significant number of texts were transmitted as copies, and a few of these survived to the present day as the received classics.

Works from this period, including the Analects, the Mencius and the Commentary of Zuo, have been admired as models of prose style by later generations.

[66] In the light of the modern understanding of Old Chinese phonology, researchers now believe that most of the characters originally classified as semantic compounds also have a phonetic nature.

The character is thought to depict bamboo or wooden strips tied together with leather thongs, a writing material known from later archaeological finds.

[70] Development and simplification of the script continued during the pre-Classical and Classical periods, with characters becoming less pictorial and more linear and regular, with rounded strokes being replaced by sharp angles.

The starting point is the Qieyun dictionary (601 AD), which classifies the reading pronunciation of each character found in texts to that time within a precise, but abstract, phonological system.

[82] Bernhard Karlgren and many later scholars posited the medials *-r-, *-j- and the combination *-rj- to explain the retroflex and palatal obstruents of Middle Chinese, as well as many of its vowel contrasts.

[97] Personal pronouns exhibit a wide variety of forms in Old Chinese texts, possibly due to dialectal variation.

[102] The forms 汝 and 爾 continued to be used interchangeably until their replacement by the northwestern variant 你 (modern Mandarin nǐ) in the Tang period.

[108] The distributive pronouns were formed with a *-k suffix:[109][110] As in the modern language, localizers (compass directions, 'above', 'inside' and the like) could be placed after nouns to indicate relative positions.

("Great Announcement", Book of Documents)[123]The negated copula *pjə-wjij 不惟 is attested in oracle bone inscriptions, and later fused as *pjəj 非.

In the Classical period, nominal predicates were constructed with the sentence-final particle *ljaj 也 instead of the copula 惟, but 非 was retained as the negative form, with which 也 was optional:[124][125] 其*ɡjəits至*tjitsarrive爾*njəjʔyou力*C-rjəkstrength也*ljajʔFP其*ɡjəits中*k-ljuŋcentre非*pjəjNEG爾*njəjʔyou力*C-rjəkstrength也*ljajʔFP其 至 爾 力 也 其 中 非 爾 力 也*ɡjə *tjits *njəjʔ *C-rjək *ljajʔ *ɡjə *k-ljuŋ *pjəj *njəjʔ *C-rjək *ljajʔits arrive you strength FP its centre NEG you strength FP(of shooting at a mark a hundred paces distant) 'That you reach it is owing to your strength, but that you hit the mark is not owing to your strength.'

[126] As in Modern Chinese, but unlike most Tibeto-Burman languages, the basic word order in a verbal sentence was subject–verb–object:[127][128] 孟子*mraŋs-*tsjəʔMencius見*kenssee梁*C-rjaŋLiang惠*wetsHui王*wjaŋking孟子 見 梁 惠 王*mraŋs-*tsjəʔ *kens *C-rjaŋ *wets *wjaŋMencius see Liang Hui king'Mencius saw King Hui of Liang.'

(Mencius 1.1/1/3)[129]Besides inversions for emphasis, there were two exceptions to this rule: a pronoun object of a negated sentence or an interrogative pronoun object would be placed before the verb:[127] 歲*swjatsyear不*pjəNEG我*ŋajʔme與*ljaʔwait歲 不 我 與*swjats *pjə *ŋajʔ *ljaʔyear NEG me wait'The years do not wait for us.'

Thus relative clauses were placed before the noun, usually marked by the particle *tjə 之 (in a role similar to Modern Chinese de 的):[132][133] 不*pjəNEG忍*njənʔendure人*njinperson之*tjəREL心*sjəmheart不 忍 人 之 心*pjə *njənʔ *njin *tjə *sjəmNEG endure person REL heart'... the heart that cannot bear the afflictions of others.'

Linguists still believe that the language lacked inflection, but it has become clear that words could be formed by derivational affixation, reduplication and compounding.

For example, the early Chinese name *kroŋ (江 jiāng) for the Yangtze was later extended to a general word for 'river' in south China.

These include terms related to rice cultivation, which began in the middle Yangtze valley: Other words are believed to have been borrowed from languages to the south of the Chinese area, but it is not clear which was the original source, e.g.

In ancient times, the Tarim Basin was occupied by speakers of Indo-European Tocharian languages, the source of *mjit (蜜 mì) 'honey', from proto-Tocharian *ḿət(ə) (where *ḿ is palatalized; cf.

[148][h] The northern neighbours of Chinese contributed such words as *dok (犢 dú) 'calf' – compare Mongolian tuɣul and Manchu tuqšan.

[191] A number of bimorphemic syllables appeared in the Classical period, resulting from the fusion of words with following unstressed particles or pronouns.