Mosasaur

During the last 20 million years of the Cretaceous period (Turonian–Maastrichtian ages), with the extinction of the ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs, mosasaurids became the dominant marine predators.

Mosasaurs breathed air, were powerful swimmers, and were well-adapted to living in the warm, shallow inland seas prevalent during the Late Cretaceous period.

[4] Currently, the largest publicly exhibited mosasaur skeleton in the world is on display at the Canadian Fossil Discovery Centre in Morden, Manitoba.

The specimen, nicknamed "Bruce", is just over 15 m (49 ft) long,[5] but this might be an overestimate as the skeleton was assembled for display prior to a 2010 reassessment of the species that found its original number of vertebrae to be exaggerated, implying that the actual size of the animal was likely smaller.

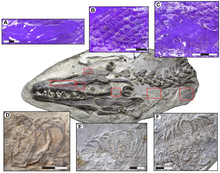

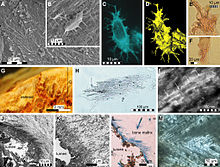

[10][11] Early reconstructions showed mosasaurs with dorsal crests running the length of their bodies, which were based on misidentified remains of tracheal cartilage.

A skeleton of Tylosaurus proriger from South Dakota included remains of the diving seabird Hesperornis, a marine bony fish, a possible shark, and another, smaller mosasaur (Clidastes).

These were once interpreted as a result of limpets attaching themselves to the ammonites, but the triangular shape of the holes, their size, and their presence on both sides of the shells, corresponding to upper and lower jaws, is evidence of the bite of medium-sized mosasaurs.

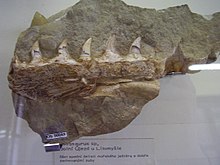

Virtually all forms were active predators of fish and ammonites; a few, such as Globidens, had blunt, spherical teeth, specialized for crushing mollusk shells.

[16] Material from Jordan has shown that the bodies of mosasaurs, as well as the membranes between their fingers and toes, were covered with small, overlapping, diamond-shaped scales resembling those of snakes.

[15] Additionally, mosasaurs had large pectoral girdles, and such genera as Plotosaurus may have used their front flippers in a breaststroke motion to gain added bursts of speed during an attack on prey.

In monitor lizards and snakes, paired fenestrae are associated with a forked tongue, which is flicked in and out to detect chemical traces and provide a directional sense of smell.

Mosasaurs were likely countershaded, with dark backs and light underbellies, much like a great white shark or leatherback sea turtle, the latter of which had fossilized ancestors for which color was also determined.

[24] A 2020 study published in Nature described a large fossilized hatched egg from Antarctica from the very end of the Cretaceous, about 68 million years ago.

[29] Sea levels were high during the Cretaceous period, causing marine transgressions in many parts of the world, and a great inland seaway in what is now North America.

Mosasaur fossils have been found in the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Portugal, Sweden, South Africa, Spain, France, Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Italy[30] Bulgaria, the United Kingdom,[31][32] Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan,[33] Japan,[34] Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Syria,[35] Turkey,[36] Niger,[37][38] Angola, Morocco, Australia, New Zealand, and on Vega Island off the coast of Antarctica.

When the French revolutionary forces occupied Maastricht in 1794, the carefully hidden fossil was uncovered, after a reward, it is said, of 600 bottles of wine, and transported to Paris.

After it had been earlier interpreted as a fish, a crocodile, and a sperm whale, the first to understand its lizard affinities was the Dutch scientist Adriaan Gilles Camper in 1799.

The Maastricht limestone beds were rendered so famous by the mosasaur discovery, they have given their name to the final six-million-year epoch of the Cretaceous, the Maastrichtian.

[49] A 2017 study by Simoes et al. noted that utilization of different methods of phylogenetic analyses can yield different findings and ultimately found an indication that tethysaurines were a case of hydropedal mosasaurs reversing back to a plesiopedal condition rather than an independent ancestral feature.

Topology A follows an ancestral state reconstruction from an implied weighted maximum parsimony tree by Simoes et al. (2017), which contextualizes a single marine origin with tethysaurine reversal.

[52] Adriosaurus suessi Dolichosaurus longicollis Komensaurus carrolli Pontosaurus kornhuberi Aigialosaurus dalmaticus Opetiosaurus bucchichi Halisaurinae Yaguarasaurus columbianus Russellosaurus coheni Romeosaurus fumanensis Tethysaurus nopcsai Pannoniasaurus inexpectatus Tylosaurinae Plioplatecarpinae Dallasaurus turneri Clidastes Derived mosasaurines

Aigialosaurus Pannoniasaurus inexpectatus Tethysaurus nopcsai Yaguarasaurus columbianus Russellosaurus coheni Carsosaurus marchesetti Komensaurus carrolli Haasiasaurus gittelmani Halisaurinae Tylosaurinae Plioplatecarpinae Dallasaurus turneri Clidastes Globidensini Prognathodontini Mosasaurini

Yaguarasaurus Russellosaurus Romeosaurus Tethysaurus Pannoniasaurus Taniwhasaurus Tylosaurus Ectenosaurus Plesioplatecarpus Angolasaurus Goronyosaurus Selmasaurus Gavialimimus Latoplatecarpus Platecarpus Plioplatecarpus Pluridens Eonatator Phosphorosaurus Halisaurus Kourisodon Clidastes Eremiasaurus Globidens Gnathomortis Prognathodon Thalassotitan Moanasaurus Carinodens Xenodens Mosasaurus Plesiotylosaurus Plotosaurus

Though no individual genus or subfamily is found worldwide, the Mosasauridae as a whole achieved global distribution during the Late Cretaceous with many locations typically having complex mosasaur faunas with multiple different genera and species in different ecological niches.