Taniwhasaurus

T. 'capensis' from present-day South Africa represents a chimera of two different mosasaur genera, potentially Prognathodon and Taniwhasaurus, but not identifiable at the species level.

The rare fossils of the axial skeleton indicate that the animal would have had great mobility in the vertebral column, but the tail would generate the main propulsive movement, a method of swimming proposed for other mosasaurids.

CT scans performed on the snout foramina of T. antarcticus show that Taniwhasaurus, like various aquatic predators today, would likely have had an electro-sensitive organ capable of detecting the movements of prey underwater.

The fossil record shows that both officially recognized species of Taniwhasaurus were endemic to the seas of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, nevertheless living in different types of bodies of waterbodies.

[4] In 1897, in his revision of the distribution of mosasaurs, Samuel Wendell Williston put Taniwhasaurus back as a separate genus, but considered it to still be close to Platecarpus.

[3][7] The specific epithet oweni is named in honor of the famous English paleontologist Richard Owen, who was the first to describe the Mesozoic marine reptiles of New Zealand.

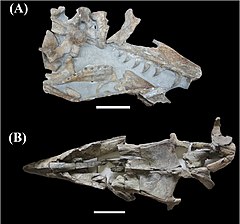

[6] Although most of these remains have been lost since the 1890s,[6] it's in 1999 that new cranial and postcranial material was discovered in the cliffs of Haumuri Bluff and that these findings were formalized by Michael W. Caldwell and his colleagues in 2005.

[2] This discovery concerns a tylosaurine specimen which heve been discovered in the Upper Campanian fossil record, cataloged IAA 2000-JR-FSM-1, containing a skull measuring 72 cm (28 in) long, teeth, some vertebrae and rib fragments.

[7] The same year, Martin and his colleagues announced the discovery of a juvenile skull considered to belong to the same species and dating from the Maastrichtian,[14] but subsequent studies are skeptical of this claim.

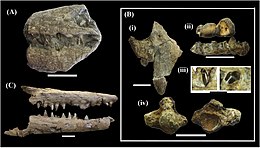

[18] In 1901, one of the sets of fossils discovered (catalogued as SAM-PK-5265[17][19]), being a few fragmentary pieces of a jawbone, was referred as belonging to a reptile considered close to the genus Mosasaurus.

This collection of fossils was later given to the Scottish paleontologist Robert Broom, who published in 1912 an article describing the same bones, along with a vertebra attributed to this specimen.

[27] In 2008, the fossil was completely reidentified by Caldwell and colleagues as a mosasaur, and classified as a new species of Taniwhasaurus, being renamed T. mikasaensis, thus keeping the specific epithet of Obata and Muramoto.

[6] When extrapolated with the proportions of a mature specimen of the closely related Tylosaurus proriger (FHSM VP-3), this yields an total length of 8.65 meters (28.4 ft).

[b][6][29][30] T. antarcticus represents a smaller species; scaling the 72 cm (28 in) long holotype skull to the same proportions approximates a total length of 5.61 meters (18.4 ft).

Like other tylosaurines, the skull of is characterized by the presence of an edentulous rostrum, an anterior process to the dentary bone, and an exclusion of the frontal from the margin of the orbit.

The centrum is shortened on the rostro-caudal side but is elongated dorso-ventrally and compressed laterally, resulting in a ventrally oval rather than circular condyle as seen in presacral vertebrae.

Distally, the right and left halves merge midway from the ventral tip of the element, creating a large anterior ridge on the vertebral column.

[6] Later discoveries of other tylosaurines, previously mentioned as belonging to distinct genera and which are now considered synonymous to Taniwhasaurus, will confirm Welles and Gregg's proposal on the phylogenetic position of this genus.

[1][25][16] In 2019, in their phylogenetic review of this group, Jiménez-Huidobro and Caldwell believe that Taniwhasaurus cannot be considered with certainty to be monophyletic, because some named species have too fragmentary fossils to be assigned concretely to the genus.

[17] A study published in 2020 by Daniel Madzia and Andrea Cau suggests a paraphyletic relationship of Tylosaurus, considering that Taniwhasaurus would have evolved from this latter, around 84 million years ago.

This neurovascular system is comparable to those present in various living and extinct aquatic tetrapods, such as cetaceans, crocodilians, plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs, which are used to stalk prey in low light conditions.

The prezygapophyses of the cervical vertebrae mark the location of the longissimus and semispinalis muscles, which partly produce the lateral flexions of the body in reptiles.

The related genus Tylosaurus would not have had overly pronounced neck mobility due to backward-curving neural spines, which more closely attaches one vertebra to another by means of ligaments and axial musculature.

[40] However, a thesis published in 2017 proves that Tylosaurus had a powerful and fast swim, due in particular to the regionalization of the caudal vertebrae, although less marked than in more derived mosasaurines.

[41] The analyzes concerning the dorsal and caudal vertebrae in Plotosaurus and Tylosaurus are similar to those found in modern cetaceans, and that therefore these would also have a carangiform swimming shape.

The relative measurements of the vertebral centra, of the morphological and phylogenetic proximity with Tylosaurus, seem to indicate that the tail of T. antarcticus would also have a very important role in movement, confirming this hypothesis.

However, the cervical vertebrae of Taniwhasaurus show an unusual range of motion in a carangiform swimmer, perhaps wider than in any other mosasaur due to the lateral compression of the vertebral centra in this area, but also at their length.

[17] Excluding the species T. 'mikasaensis', the presence of T. oweni and T. antarcticus shows that the genus would have been endemic to Gondwana,[25] and more specifically in the Cretaceous Austral Fauna of the Weddellian Province, a geographic area including Antarctica, New Zealand and Patagonia.

The specific part of the site reaches a maximum thickness of 240 meters (790 ft) and lithologically the unit is a loosely cemented massive gray siltstone with locally limited interbeds of fine sandstone.

The cores of the concretions present in the formation appear to be fossilized bones, shells or even wood, indicating that the environment of deposit would have been the lower zone of a foreshore.