Timeline of mosasaur research

Myths about warfare between serpentine water monsters and aerial thunderbirds told by the Native Americans of the modern western United States may have been influenced by observations of mosasaur fossils and their co-occurrence with creatures like Pteranodon and Hesperornis.

[1] The scientific study of mosasaurs began in the late 18th century with the serendipitous discovery of a large fossilized skeleton in a limestone mine near Maastricht in the Netherlands.

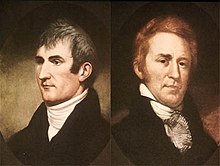

[2] The fossils were studied by local scholar Adriaan Gilles Camper, who noted a resemblance to modern monitor lizards in correspondence with renowned French anatomist Georges Cuvier.

[4] By this time the first mosasaur fossils from the United States were discovered by the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and the first remains in the country to be scientifically described were reported slightly later from New Jersey.

[5] This was followed by an avalanche of discoveries by the feuding Bone War paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Kansas.

[7] Later Samuel Wendell Williston mistook fossilized tracheal rings for the remains of a fringe of skin running down the animal's back, which subsequently became a common inaccuracy in artistic restorations.

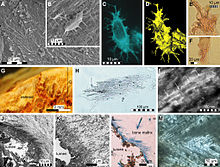

[15] In 2013, Lindgren, Kaddumi, and Polcyn reported the discovery of a Prognathodon specimen from Jordan that preserved the soft tissues of its scaley skin, flippers and tail.

[54] He regarded Platecarpus and Tylosaurus as deep water animals but concluded that the biostratigraphic evidence from the Smoky Hill mosasaurs suggested that the Chalk's depositional environment was becoming shallower and nearer to the ancient coastline over time.

[76] Russell also argued that by the end of the Late Cretaceous, mosasaurs were converging on the body plan that characterized the first ichthyosaurs during the Triassic period and gradually replacing these older marine reptiles.