Mosasaurus

The genus was one of the first Mesozoic marine reptiles known to science—the first fossils of Mosasaurus were found as skulls in a chalk quarry near the Dutch city of Maastricht in the late 18th century, and were initially thought to be crocodiles or whales.

Mosasaurus possessed excellent vision to compensate for its poor sense of smell, and a high metabolic rate suggesting it was endothermic ("warm-blooded"), an adaptation in squamates only found in mosasaurs.

From an ecological standpoint, Mosasaurus probably had a profound impact on the structuring of marine ecosystems; its arrival in some locations such as the Western Interior Seaway in North America coincides with a complete turnover of faunal assemblages and diversity.

[23] The fourth species M. lemonnieri was described in 1889 by Louis Dollo on the basis of a relatively complete skull discovered in a quarry owned by the Solvay S.A. company in the Ciply Basin of Belgium.

[10] In 2004, Eric Mulder, Dirk Cornelissen, and Louis Verding suggested M. lemonnieri could be a juvenile form of M. hoffmannii based on the argument that significant differences could be explained by age-based variation.

[48] The species is named in honor of Alfred Beaugé, director at the time of the OCP Group, who invited Arambourg to participate in the research project and helped him to provide local fossils.

[50][51] Schlegel's hypothesis was largely ignored by contemporary scientists but became widely accepted by the 1870s when Othniel Charles Marsh and Cope uncovered more complete mosasaur remains in North America.

In M. hoffmannii, the top margin of the dentary is slightly curved upwards;[5] this is also the case with the largest specimens of M. lemonnieri, although more typical skulls of the species have a near-perfectly straight jawline.

[5] The quadrate also housed the hearing structures, with the eardrum residing within a round and concave depression in the outer surface called the tympanic ala.[67] The trachea likely stretched from the esophagus to below the back end of the lower jaw's coronoid process, where it split into smaller pairs of bronchi which extended parallel to each other.

[48] One indeterminate specimen of Mosasaurus similar to M. conodon from the Pembina Gorge State Recreation Area in North Dakota was found to have an unusual count of sixteen pterygoid teeth, far greater than in known species.

The femur itself is about twice as long as it is wide and ends at the distal side in a pair of distinct articular facets (of which one connects to the ilium and the other to the paddle bones) that meet at an angle of approximately 120°.

(hover over or click on each skeletal component to identify the structure) Because nomenclatural rules were not well-defined at the time, 19th century scientists did not give Mosasaurus a proper diagnosis during its initial descriptions, which led to ambiguity in how the genus is defined.

[44][81] He proposed that Mosasaurus evolved from a Clidastes-like mosasaur, and diverged into two lineages, one giving rise to M. conodon and another siring a chronospecies sequence which contained in order of succession M. ivoensis, M. missouriensis, and M.

In many mosasaurs like Prognathodon and M. lemonnieri, this function mainly served to allow ratchet feeding, in which the pterygoid and jaws would "walk" captured prey into the mouth like a conveyor belt.

The paddles' steering function was enabled by large muscle attachments from the outwards-facing side of the humerus to the radius and ulna and modified joints allowed an enhanced ability of rotating the flippers.

The eye sockets were located at the sides of the skull, which created a narrow field of binocular vision at around 28.5°[25][94] but alternatively allowed excellent processing of a two-dimensional environment, such as the near-surface waters inhabited by Mosasaurus.

[68] Lingham-Soliar (1995) suggested that Mosasaurus had a rather "savage" feeding behavior as demonstrated by large tooth marks on scutes of the giant sea turtle Allopleuron hoffmanni and fossils of re-healed fractured jaws in M.

The positioning of both bite marks are at the direction the nautiloid's head would have been facing, indicating it was incapable of escaping and was thus already sick or dead during the attacks; it is possible this phenomenon was from a parent mosasaur teaching its offspring about cephalopods as an alternate source of prey and how to hunt one.

Modern crocodiles commonly attack each other by grappling an opponent's head using their jaws, and Lingham-Soliar hypothesized that Mosasaurus employed similar head-grappling behavior during intraspecific combat.

Extensive amounts of bony callus almost overgrowing the tooth socket are present around the fracture along with various osteolytic cavities, abscess canals, damages to the trigeminal nerve, and inflamed erosions signifying severe bacterial infection.

Considering how the individual was able to survive such conditions for an extended period of time, Schulp and colleagues speculated it switched to a foraging-type diet of soft-bodied prey like squid that could be swallowed whole to minimize jaw use.

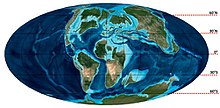

These localities include the Midwest and East Coast of the United States, Canada, Europe, Turkey, Russia, the Levant, the African coastline from Morocco[109] to South Africa, Brazil, Argentina, and Antarctica.

Marine reptile assemblages in the New Jersey region of the province are generally equivalent with those in Europe; the mosasaur faunae are quite similar but exclude M. lemonnieri, Carinodens, Tylosaurus, and certain species of Halisaurus and Prognathodon.

[110] Many of the earliest fossils of Mosasaurus were found in Campanian stage deposits in North America, including the Western Interior Seaway, an inland sea which once flowed through what is now the central United States and Canada, and connected the Arctic Ocean to the modern-day Gulf of Mexico.

[111] The fossil assemblages throughout these regions suggest a complete faunal turnover when M. missouriensis and M. conodon appeared at 79.5 Ma, indicating that the presence of Mosasaurus in the Western Interior Seaway had a profound impact on the restructuring of marine ecosystems.

[120][111][121] In what is now Alabama within the Southern Interior Subprovince, most of the key genera including sharks like Cretoxyrhina and the mosasaurs Clidastes, Tylosaurus, Globidens, Halisaurus, and Platecarpus disappeared and were replaced by Mosasaurus.

[120] Some Niobraran genera such as Tylosaurus,[123] Cretoxyrhina,[124] hesperornithids,[125] and plesiosaurs including elasmosaurs such as Terminonatator[126] and polycotylids like Dolichorhynchops[127] maintained their presence until around the end of the Campanian, during which the entire Western Interior Seaway started receding from the north.

The scientists utilized an interpretation that differences in isotope values can help explain the level of resource partitioning because it is influenced by multiple environmental factors such as lifestyle, diet, and habitat preference.

[25] During the late Maastrichtian, global sea levels dropped, draining the continents of their nutrient-rich seaways and altering circulation and nutrient patterns, and reducing the number of available habitats for Mosasaurus.

This formed through a combination of catastrophic seismic and geological disturbances, mega-hurricanes, and giant tsunamis caused by the impact of the Chicxulub asteroid that catalyzed the K-Pg extinction event.