Mouse mill motor

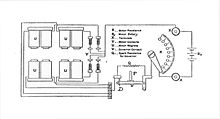

As the mouse mill motor was simple to construct and its speed could easily be governed, it was later used to drive automatic recorders in telegraphy.

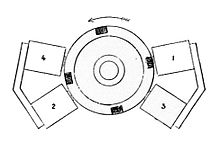

The rotor is made of a light brass wheel, with a number of soft iron bars or "attractors" mounted around its rim and parallel to the axis.

[2] Many of the early motors were made by the scientific instrument maker Daniel Davis of Boston,[3] who sold them as the "Revolving Armature Engine".

As it approaches closer, the current is then switched off and so the bar continues to rotate past the magnet, rather than being attracted to it and stopping there.

It is then simpler to use a simple single-lobed cam, on a shaft geared up to be driven at four, six or eight times the rotor speed, according to the number of bars.

The use of a geared-up camshaft, as was common on the large power-producing motors, is also beneficial to permitting a smaller and more sensitive centrifugal governor.

Some decades after its first development, the motor was used in telegraphy to power the paper feed mechanism for both Kelvin's and Muirhead's syphon recorders.

Kelvin's design instead used a hollow glass pen with an electrostatic charge to propel ink from the syphon tube.

Where a telegraph machine depending on precise timing to signal letters, a synchronous motor such as that developed by Paul Le Cour was used.