Muisca

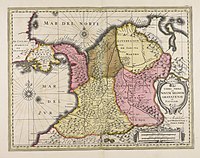

The territory of the Muisca spanned an area of around 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) from the north of Boyacá to the Sumapaz Páramo and from the summits to the western portion of the Eastern Ranges.

Their territory bordered the lands of the Panche in the west, the Muzo in the northwest, the Guane in the north, the Lache in the northeast, the Achagua in the east, and the Sutagao in the south.

The descendants of the Muisca are often found in rural municipalities including Cota, Chía, Tenjo, Suba, Engativá, Tocancipá, Gachancipá, and Ubaté.

Knowledge of events up until 1450 is mainly derived from mythological contexts, but thanks to the Chronicles of the West Indies we do have descriptions of the final period of Muisca history, prior to Spanish arrival.

Excavations in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense (the highlands of Cundinamarca and Boyacá departments) show evidence of human activity since the Archaic stage at the beginning of the Holocene era.

Other archaeological traces in the region of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense have led scholars to talk about an El Abra Culture: In Tibitó, tools and other lithic artifacts date to 9740 BCE; on the Bogotá savanna, especially at Tequendama Falls, other lithic tools dated a millennium later were found that belonged to specialized hunters.

Scholars agree that the group identified as Muisca migrated to the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Formative era (between 1000 BCE and 500 CE), as shown by evidence found at Aguazuque and Soacha.

Zipa Saguamanchica (ruled 1470 to 1490) was in a constant war against aggressive tribes such as the Sutagao, and especially the Panche, who would also make difficulties for his successors, Nemequene and Tisquesusa.

The Caribs were also a permanent threat as rivals of the zaque of Hunza, especially for the possession of the salt mines of Zipaquirá, Nemocón and Tausa.

Many Chibcha words were absorbed or "loaned" into Colombian Spanish: The Muisca had an economy and society considered to have been one of the most powerful of the American Post-Classic stage, mainly because of the precious resources of the area: gold and emeralds.

The scholar Paul Bahn said: "the Andean cultures mastered almost every method of textile weaving or decoration now known, and their products were often finer than those of today.

Pre-Columbian Muisca patterns appear in various seals of modern municipalities located on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, for instance Sopó and Guatavita, Cundinamarca.

Oral tradition suggests that every family gave up a child for sacrifice, that the children were regarded as sacred and cared for until the age of 15, when their lives were then offered to the Sun-god, Sué.

They developed a vigesimal (based on 20) calendar and knew exactly the timing of the summer solstice (June 21), which they considered the Day of Sué, the Sun god.

The origin of the legend of El Dorado (Spanish for "The Golden One") in the early 16th century may be located in the Muisca Confederation[citation needed].

In 1542 Gonzalo Suárez Rendón finally put down the last resistance and the territories of the Confederations were shared by Belalcazar, Federmann, and De Quesada.

The territory of the Muisca, located in a fertile plain of the Colombian Andes that contributed to make one of the most advanced South American civilizations, became part of the colonial region named Nuevo Reino de Granada.

Tenjo was reduced to 54% of its original size after 1934, and the Indigenous lands in Suba, a northern region in modern-day Bogotá, which had been recognized and protected by the crown, were taken away by the republican governments following a strategy of suppression of the native culture and ethnic presence in the country's largest urban centres.

The Reservation of Cota was re-established on land bought by the community in 1916, and then recognized by the 1991 constitution; the recognition was withdrawn in 1998 by the state and restored in 2006.

In that congress, they founded the Cabildo Mayor del Pueblo Muisca, affiliated to the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC).

They support the communities of Ubaté, Tocancipá, Soacha, Ráquira, and Tenjo in their efforts to recover their organizational and human rights.

They defended the natural reserves like La Conejera, part of the Suba Hills that is considered by the Shelter's Council to be communal land.

The community of Bosa made important achievements in its project of natural medicine in association with the Paul VI Hospital and the District Secretary of Health of Bogotá.

Research shows that this site was the cradle of an advanced society whose process of consolidation was cut short by the Spanish conquest.

[19] This search for an identity resulted in giving emphasis to the Muisca culture and overlooking other native nations, which were seen as wild people.

In 1849 president Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera invited Italian cartographer Agustín Codazzi, who led the Geography Commission with Manuel Ancízar and did descriptive studies of the national territory and an inventory of the archaeological sites.

[20] Argüello García pointed out that the goal of that expedition in the context of the new nation was to underline the pre-Hispanic societies and in that sense, they centered on the Muisca culture as the main model.

[21] An objection to that point of view came from Vicente Restrepo: his work Los chibchas antes de la conquista española[22] showed them as barbarians.

Wenceslao Cabrera Ortíz was the one who concluded that the Muisca were migrants to the highlands; in 1969 he published on this[24] and reported about excavations at the El Abra archaeological site.

[19] Recent archaeological work has also concentrated on the creation and composition of Muisca goldwork, with this data being made available for wider research.

Showing the Zipa , Zaque , and Independent territories

Carved in stone by Bogotan sculptor María Teresa Zerda

Archaeology Museum, Sogamoso

Gold Museum, Bogotá

Archaeology Museum of Sogamoso

The zipa was richly ornamented in gold and expensive cloth