Muromachi period

The period ended in 1573 when the 15th and last shogun of this line, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, was driven out of the capital in Kyoto by Oda Nobunaga.

Yoshimitsu allowed the constables, who had had limited powers during the Kamakura period, to become strong regional rulers, later called daimyōs.

In time, the Ashikaga family had its own succession problems, resulting finally in the Ōnin War (1467–77), which left Kyoto devastated and effectively ended the national authority of the bakufu.

Wanting to improve relations with China and to rid Japan of the wokou threat, Yoshimitsu accepted a relationship with the Chinese that was to last for half a century.

Zen played a central role in spreading not only religious teachings and practices but also art and culture, including influences derived from paintings of the Chinese Song (960–1279), Yuan, and Ming dynasties.

During the Muromachi period, the re-constituted Blue Cliff Record became the central text of Japanese Zen literature; it still holds that position today.

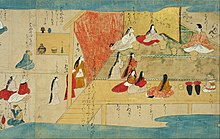

[2] Art of all kinds—architecture, literature, Noh drama, Kyōgen (comedy), poetry, sarugaku (folk entertainment), the tea ceremony, landscape gardening, and flower arranging—all flourished during Muromachi times.

Shinto, which lacked its own scriptures and had few prayers, had, as a result of syncretic practices begun in the Nara period, widely adopted Shingon Buddhist rituals.

The Mongol invasions in the late thirteenth century, however, evoked a national consciousness of the role of the kamikaze in defeating the enemy.

This chronicle emphasized the importance of maintaining the divine descent of the imperial line from Amaterasu to the current emperor, a condition that gave Japan a special national polity (kokutai).

Besides reinforcing the concept of the emperor as a deity, the Jinnōshōtōki provided a Shinto view of history, which stressed the divine nature of all Japanese and the country's spiritual supremacy over China and India.

Shukyu Banri, a priest and a composer of Chinese-style poems, went down to Mino Province in the Onin War, and then left for Edo at Dokan Ota's invitation.

The Italian Jesuit, Alessandro Valignano (1539–1606), wrote:"The people are white (not dark-skinned) and cultured; even the common folk and peasants are well brought up and are so remarkably polite that they give the impression that they were trained at court.

[4][5] The new Zen monasteries, with their Chinese background and the martial rulers in Kamakura sought to produce a unique cultural legacy to rival the Fujiwara tradition.

[6] The Ōnin War (1467–77) led to serious political fragmentation and obliteration of domains: a great struggle for land and power ensued among bushi chieftains and lasted until the mid-sixteenth century.

Rather than disrupting the local economies, however, the frequent movement of armies stimulated the growth of transportation and communications, which in turn provided additional revenues from customs and tolls.

The Portuguese landed in Tanegashima south of Kyūshū in 1543 and within two years were making regular port calls, initiating the century-long Nanban trade period.

The Japanese began to attempt studies of European civilization in depth, and new opportunities were presented for the economy, along with serious political challenges.

European firearms, fabrics, glassware, clocks, tobacco, and other Western innovations were traded for Japanese gold and silver.

Christianity affected Japan, largely through the efforts of the Jesuits, led first by the Spanish Francis Xavier (1506–1552), who arrived in Kagoshima in southern Kyūshū in 1549.

Although foreign trade was still encouraged, it was closely regulated, and by 1640, in the Edo period, the exclusion and suppression of Christianity became national policy.