Music of Mesopotamia

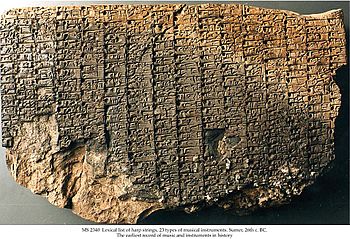

Using this cuneiform script, they recorded texts that listed genres and song titles, included instructions on how to play instruments, and articulated their music theory.

[8] In a ritual closely associated with a drum described in an Akkadian text,[9] a bull was brought to the temple and offerings were made to Ea, god of music and wisdom.

[12] The Akkadian word for music, nigūtu, also meant ‘joy’ and ‘merriment’, well illustrated by a seal in the Louvre showing a peaceful scene of a shepherd playing a flute to his flock.

Their footmen struck to the sound of drum, cymbal and shrill double-flutes, and when the fierce Assyrian horsemen charged they did so to the clashing of iron bells (like modern sleigh-bells), with which their harness was hung.

The Babylonians, Hittites, Canaanites, Syrian Phoenicians, Jews, Egyptians and Lydian Greeks yielded up their goods and treasure to these martial pipings, and gold, silver, lapis lazuli, gums, spices, war-chariots, horses, cattle and slaves pour into the Assyrian capital to the tempo of their military.

[26][27] Extant clay tablets often record information on student activities in edubbas, and indicate that their examinations included questions on differentiating and identifying instruments, singing technique, and analyzing compositions.

[37] Among the elite class, children received a comprehensive education in reading, writing, religion, the sciences, law, and medicine, among other topics; whether music was included is largely uncertain.

[40] The gala (Akkadian: kalû)[41] musician was closely associated with temple rituals; it has been suggested by the musicologist Piotr Michalowski that their job was "normally less glamorous and perhaps temporary".

[50] In the Royal Cemetery at Ur, archaeologist Leonard Woolley found a girl musician lying down, harp in hand, inside the tomb of Queen Puabi.

[54] Shulgi seemed to enjoy playing all instruments except the reed pipe, which he believed brought sadness to the spirit, whereas music should bring joy and cheer.

[56] Shulgi generously funded Sumer's two major edubbas, those of Ur and Nippur; in return, Sumerian poets composed hymns of glorification in his honor.

[68] Determinatives, or unvocalized logograms that show the category of a noun,[69] inform the reader whether the object in question is, for example, made of wood (𒄑, giš), is a person (𒇽, lú), or is a building (𒂍, é).

[75] Several balags are known to have been minor gods related to the sun-god Utu, associated with law and justice, including ‘Let me live by His Word’, ‘Just Judge’, and ‘Decision of Sky and Earth’.

[82] While the exact nature of these performances may never be known,[83] musicologist Peter van der Merwe speculates that the vocal tone or timbre was probably similar to the "pungently nasal sound" of the narrow-bore reed pipes.

[87] The psaltery, whose strings are parallel to the soundbox and stretched across its full length,[17] first appears in the 8th century BCE on a Phoenecian ivory piece (British Museum).

[111] When used by royalty or as part of a religious ceremony, string instruments were adorned with precious metals and stones, such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and mother of pearl.

[113] The oldest pictorial record of lute playing is on an Uruk-period cylinder seal (British Museum[115]) dating to 3100 BCE that depicts a female figure with a long-necked instrument sitting at the back of a boat in a musician's posture.

Kramer details some elements of hymnal organization:[144] As to structure, the hymns are frequently divided into songs of varying lengths separated from each other by brief antiphonal responses; others consist of a number of four-line strophes.

[163]David Wulstan offers an excerpt from a small fragment of such a text:[166] If the harp is in išartum tuning, You have played the qablitum interval You adjust strings II and IX

[168] The seven heptatonic scales (and their Greek equivalents) were: išartu (Dorian), kitmu (Hypodorian), embūbu (Phrygian), pūtu (Hypophrygian), nīd qabli ( Lydian), nīš gabarî (Hypolydian), qablītu (Mixolydian).

[170] Marcelle Duchesne-Guillemin lists the four rules that governed the tuning of these instruments:[168] 1. an ascending fifth and a descending fourth are used; 2. the heptachord is a limit not to be exceeded in the alternating process.

[145] Musicologist Egon Wellesz suggested that in Mesopotamian thought, numbers represented a sacred force and that the seven notes of their heptatonic scales were symbolically linked to the seven heavenly bodies, including the Sun, Moon, and the five visible planets:[173][l] Šiḫṭu (Mercury), Dilbat (Venus), Ṣalbatānu (Mars), White Star (Jupiter), and Kayyāmānu (Saturn), known from the second millennium BCE.

[179] Musicologist Peter van der Merwe writes:[180] The harps, lyres, lutes, and pipes of Mesopotamia spread into Egypt, and later into Greece, and, mainly through the Greek influence, to Rome.

[180]The lute, or sinnitu,[181] may have originated in Mesopotamia, or it may have been introduced from surrounding regions, such as by the Hittites, Hurrians or Kassites,[182] or from the west by nomadic people of the semidesert plains of Syria.

[188] The dulcimer spread throughout the world, its variants and derivatives known in Persia as the santur; in places of Islamic influence (e.g., Egypt, Georgia, Greece, India, and Slovenia) as the senterija; in China and India as yang-ch’in; [n] in Mongolia as youchin; in Korea as yanggûm; in Thailand as kim; in eastern Europe as kim balon; in western Europe as tympanon; in Britain, North America, and New Zealand as the ‘dulcimer’ (when struck) or the ‘psaltery’ (when plucked).

[176] For example, pottery in the Mediterranean and Near East showed a common, stereotyped motif — a typical musical ensemble that could be found throughout the region, consisting of lyres, double pipes, and percussion.

Variations in this motif show local adaption, for example in ancient Greece the asymmetrical West Semitic lyres are replaced with Hellenistic instruments.

[201] In the first centuries CE, a certain type of clapper was simultaneously depicted not only in Egypt, but on mosaics in Hama and Carthage, on Roman sarcophagi, on Sasanian silverware, and in Byzantine manuscripts.

The practice of deifying string instruments was sometimes echoed in Classical Greece, but the mythology was modified resulting in the Greek ‘lyre heroes’ such as Orpheus, Amphion, Cadmus and Linus.

In the 1970s, during an ideological shift among the Ba'th party toward preservation of pre-Arab cultural heritage,[210] the garment designers and musicians of the Iraqi Fashion House presented "a historical show inspired by the civilizations of Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, Assyria, Basra, Kufa, Baghdad, Samarra and Mosul, dating from past [millennia] to the present day.”[211] Performances of a modern dulcimer are frequently featured on Iraqi television.