Musical literacy

[28] Auditory-oriented education teaches comprehensive listening and aural perception against the "backdrop of a host of norms associated with the style, genre, and period categories, and the individual compositional corpus".

[30] It is in this department that conventional classroom education often fails the individual in their acquisition of complete musical literacy as not only have "researchers pointed out that children coming to school do not have the foundational aural experiences with music to the extent that they have had with language",[31] but the "exclusive concentration on reading [and thus lack of listening] has held back the progress of countless learners, while putting many others off completely".

These aspects of musical literacy development coalesce into various educational practices that approach these types of visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic learning in different ways.

Gudmundsdottir[61] references Fine, Berry & Rosner[62] when she notes that "successful music reading on an instrument does not necessarily require internal representations of pitch as sight-singing does"[63] and proficiency in one area does not guarantee skill in the other.

The ability to link the sound of a note with its printed notation counterpart is a cornerstone in highly developed musical readers [64] and allows them to ‘read ahead’ when ‘sight-reading’ a piece due to such aural recollections.

[68] Contrastingly, "rhythm production is [universally] difficult without auditory coding"[69] as all musicians "rely on internal mental representations of musical metre [and temporal events] as they perform".

[70] In the context of reading and writing music in the school classroom, Burton[71] saw that "[students] were making their own sense of rhythm in print"[72] and would self-correct when they realised that their aural perception of a rhythmic pattern did not match what they had transcribed on the manuscript.

For instance, encouraging young beginners to invent their own visual representations of pieces they know aurally provides them with the "metamusical awareness that will enhance their progress toward understanding why staff notation looks and works the way it does".

[77] Similarly, for children younger than six years old, translating prior aural knowledge of melodies into fingerings on an instrument (i.e. kinesthetic learning) sets the foundation for introducing visual notation later and maintains the ‘fun’ element of developing musical literacy.

[78] These stages of development in reading music notation are outlined by Mills & McPherson[79] as follows: There are various schools of thought/pedagogy that translate these principles into practical teaching methods.

This technique was adapted from the teachings of Guido d’Arezzo, an 11th-century monk, who used the tones, ‘Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La’ from the ‘Hymn to St. John’ (International Kodaly Society, 2014) as syllabic representations of pitch.

The work of Sarah Glover and (continued by) John Curwen throughout England in the 19th Century meant that ‘Moveable-Doh’ solfa became the "favoured pedagogical tool to teach singers to read music".

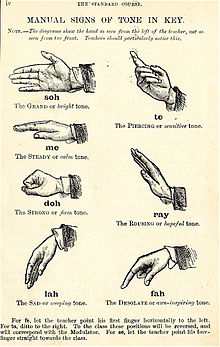

[84] In addition to the auditory-linguistic aid of syllable-to-pitch, John Curwen also introduced a kinesthetic element where different hand signs were applied to each tone of the scale.

Methods such as Kodály's, however — which rely on sound to inform the visual element of conventional staff notation — fall short for learners who are unable to see.

"No matter how brilliant the ear and how good the memory, literacy is essential for the blind student too",[89] and unfortunately conventional staff notation fails to cater to visually-impaired needs.

[107] For instance, young children exhibited a 46% increase in spatial IQ — essential for higher mind capacities involving complex arithmetic and science — after developing aspects of their musical literacy.

[114] Due to these various factors and impacts, Williams (1987)[115] finds herself of the opinion that "[musical] literacy gives dignity as well as competence, and is of the utmost importace to self-image and success... [it gives the] great joy of learning... the thrill of participation, and the satisfaction of informed listening".