NIMBY

[4] Some examples of projects that have been opposed by nimbys include housing development[5] (especially for affordable housing[6] or trailer parks[7]), high-speed rail lines,[8] homeless shelters,[9] day cares,[10] schools, universities and colleges,[11][12] bike lanes and transportation planning that promotes pedestrian safety infrastructure,[13] solar farms,[14] wind farms,[15] incinerators, sewage treatment systems,[16] fracking,[17] and nuclear waste repositories.

agencies need to be better coordinated and the "nimby" (not in my backyard) syndrome must be eliminated.The article may have been quoting Joseph A. Lieberman, a member of the United States Atomic Energy Commission.

[35] Beyond their impact on any single development or neighborhood, NIMBY organizations and policies are now painted as worsening racial segregation, deepening economic inequality, and limiting the overall supply of affordable housing.

[39] In that regard, "Not in My Neighborhood," by author and journalist Antero Pietila, describes the toll NIMN politics had on housing conditions in Baltimore throughout the 20th century and the systemic, racially based citywide separation it caused.

CAVE/BANANA people often express their views publicly by attending community meetings,[50] writing letters to the local newspaper, or calling in to talk radio shows, similar to NIMBYs.

Robert D. Bullard, Director of the Environmental Justice Resource Center at Clark Atlanta University, has argued that official responses to NIMBY phenomena have led to the PIBBY principle.

Proponents of development may accuse locals of egotism, elitism, parochialism, drawbridge mentality, racism and anti-diversity, the inevitability of criticism, and misguided or unrealistic claims of prevention of urban sprawl.

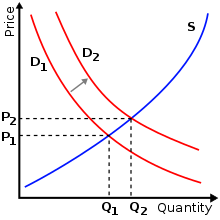

[opinion] Studies show that stricter land use regulation, such as the kind that arises from NIMBY advocacy, raises the price of housing, and consequently increases cost of living.

[71] A 1994 paper by Michael Gerrard found that NIMBY movements generally oppose three types of facilities: waste disposal, low-income housing, and social services (such as homeless shelters).

[72] An Australian politician, Zali Steggall, representing Sydney Manly Beach, advocates action on climate change, including the installation of wind turbines.

[74][75] In Vancouver, the city hall's licensing department rejected a day care's expansion from 8 to 16 kids after a small number of neighbors attended public meetings in 2023 to discuss the parking issues, noise, and traffic the additional children would bring to the neighborhood.

[79] In February 2013, some residents of Lunenburg County opposed wind farms being built in the area, saying, "It's health and it's property devaluation" and "This is an industrial facility put in the middle of rural Nova Scotia.

[83] However, in the case of China, many socially harmful projects simply continue their operation or relocate once media attention subsides and government authorities start to suppress the protestors [zh].

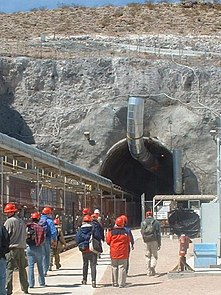

[83] The Chinese government has also been accused of "weaponizing" NIMBY movements abroad through influence operations that drive opposition against perceived economic threats such as the development projects that compete with the rare earth industry in China.

[104] In 2007, residents of the affluent English village of Ashtead, Surrey, which lies on the outskirts of London, objected to the conversion of a large, £1.7 million residential property into a family support centre for relatives of wounded British service personnel.

BBC News Online reported that many residents of conservative constituencies were launching objections to the HS2 route based on the effects it would have on them, whilst also showing concerns that HS2 is unlikely to have a societal benefit at a macro level under the current economic circumstances.

As a result, seventy-one percent of ELI households are forced to spend over half of their income on housing costs, leading to severe financial burdens.

[139] However, research suggests that proactive outreach and communication by affordable housing developers and proponents through the leveraging of social marketing and positive messaging can overcome common NIMBY barriers.

The real issue was the FAA planned the flight paths for the airport over expensive neighborhoods of south Orange County and residents feared that their property values would decrease.

[145][146] In 2022, California governor Gavin Newsom declared that "nimbyism is destroying the state" and promised to hold cities and counties accountable for stopping new housing development.

Nimbys have cited negative impact on local communities, low affordable housing quotas, restrictions on buildings' shadows, increased car traffic, and concerns with parking as reasons for opposing projects.

[163] Ultimately, the plan was revised to transform the existing SR-80 (Southern Boulevard) into a full expressway to minimize disruptions to local residents and businesses,[164] however all of the proposals were later abandoned.

[165] In 1959, when Deerfield officials learned that a developer building a neighborhood of large new homes planned to make houses available to African Americans, they issued a stop-work order.

In 2002, due to opposition from neighborhoods along the corridor, two state representatives from the suburbs of Bloomington and Edina passed a legislative ban that prohibited further study, discussion, funding, and construction of the project.

[169] In 1858, a group of residents in Staten Island burned down the New York Marine Hospital, at the time the largest quarantine facility in the United States, citing its negative effect on local property values.

[183] Community opposition also led to the cancellation of a proposed extension of the New York City Subway's Astoria Line (carrying the N and W trains) to LaGuardia Airport.

[184][185] Similarly, opposition has stopped any proposal to build a bridge or tunnel across the Long Island Sound with some believing it will harm their communities with an influx of unwanted traffic as well as concerns regarding the environment and the number of homes that would be cleared as a result.

[189] The project received extensive backlash from an organized group of affected property owners and farmers, citing the massive loss of land as a negative impact on Jefferson County's agricultural industry.

"[195] In a 2020 paper exploring the relationship between homeowners' self-interest and pro-NIMBY attitudes among both self-identified liberals and conservatives, William Marble and Clayton Nall note: “Whether they are responding to different housing policies, responding to persuasive political messaging, or evaluating hypothetical proposals for local development, homeowners remain opposed to local development policies that threaten their self-interest.“[196] Historian Nancy Shoemaker cites "Not-in-My-Backyard Colonialism" as one of twelve types of colonialism, in which an area is colonized to dispose of convicts or conduct dangerous experiments.

[197] Various means to overcome NIMBY opposition to infrastructure or development have been used, including persuasion, leaving the decision to an appointed board, or broadening the decision-making community (such as by overriding municipal zoning rules with countywide or statewide regulations).