Terminology of the Low Countries

The complicated nomenclature is a source of confusion for outsiders, and is due to the long history of the language, the culture and the frequent change of economic and military power within the Low Countries over the past 2,000 years.

In the 4th and 5th centuries a Frankish confederation of Germanic tribes significantly made a lasting change by entering the Roman provinces and starting to build the Carolingian Empire, of which the Low Countries formed a core part.

After the Frankish empire was divided several times, most of it became the Duchy of Lower Lorraine in the 10th century, where the Low Countries politically have their origin.

Some of these became so powerful, that their names were used as a pars pro toto for the Low Countries, i.e., Flanders, Holland and to a lesser extent Brabant.

[14] By the late 14th century, þēodisc had given rise to Middle English duche and its variants, which were used as a blanket term for all the non-Scandinavian Germanic languages spoken on the European mainland.

Dutch: ridder] is a knight) in which case linguistic and/or geographic pointers need to be used to determine or approximate what the author would have meant in modern terms, which can be difficult.

[17] For example, in his poem Constantyne, the English chronicler John Hardyng (1378–1465) specifically mentions the inhabitants of three Dutch-speaking fiefdoms (Flanders, Guelders and Brabant) as travel companions, but also lists the far more general "Dutchemēne" and "Almains", the latter term having an almost equally broad meaning, though being more restricted in its geographical use; usually referring to people and locaties within modern Germany, Switzerland and Austria: He went to Roome with greate power of Britons strong, with Flemynges and Barbayns, Henauldes, Gelders, Burgonians, & Frenche, Dutchemēne, Lubārdes, also many Almains.

[18] He went to Rome with a large number of Britons, with Flemings and Brabanters, Hainuyers, Guelders, Burgundians, and Frenchmen, "Dutchmen", Lombards, also many Germans.

Many factors facilitated this, including close geographic proximity, trade and military conflicts, for instance the Anglo-Dutch Wars.

Because medieval trade focused on travel by water and with the most heavily populated areas adjacent to Northwestern France, the average 15th century Dutchman stood a far greater chance of hearing French or English than a dialect of the German interior, despite its relative geographical closeness.

[34] In the second half of the 16th century the neologism "Nederduytsch" (literally: Nether-Dutch, Low-Dutch) appeared in print, in a way combining the earlier "Duytsch" and "Nederlandsch" into one compound.

[35] Though "Duytsch" forms part of the compound in both Nederduytsch and Hoogduytsch, this should not be taken to imply that the Dutch saw their language as being especially closely related to the German dialects spoken in Southerwestern Germany.

On the contrary, the term "Hoogduytsch" specifically came into being as a special category because Dutch travelers visiting these parts found it hard to understand the local vernacular: in a letter dated to 1487 a Flemish merchant from Bruges instructs his agent to conduct trade transactions in Mainz in French, rather than the local tongue to avoid any misunderstandings.

Dutch humanists, started to use "Duytsch" in a sense which would today be called "Germanic", for example in a dialogue recorded in the influential Dutch grammar book "Twe-spraack vande Nederduitsche letterkunst", published in 1584: R. ghy zeyde flux dat de Duytsche taal by haar zelven bestaat/ ick heb my wel laten segghen, dat onze spraack uyt het Hooghduytsch zou ghesproten zyn.

Beginning in the second half of the 16th century, the nomenclature gradually became more fixed, with "Nederlandsch" and "Nederduytsch" becoming the preferred terms for Dutch and with "Hooghduytsch" referring to the language today called German.

[39] Place names with "low(er)" or neder, lage, nieder, nether, nedre, bas and inferior are used everywhere in Europe.

For example, Niderlant is mentioned in the 12th century legend Nibelungenlied, where it is located in the lower Rhine region around the German town Xanten.

[40] In this context the higher ground is around the Upper Rhine plain around the German city of Worms, where the events of the poem take place.

The politically related geographical location of the "upper" ground changed over time tremendously, and rendered over time several names for the area now known as the Low Countries: Apart from its topographic usage for the then multi-government area of the Low Countries, the 15th century saw the first attested use of Nederlandsch as a term for the Dutch language, by extension hinting at a common ethnonym for people living in different fiefdoms.

It is rare in general use, but remains common in academic jargon, especially in reference to art or music produced anywhere in the Low Countries during the 15th and early 16th centuries.

The Low Countries (Dutch: Lage Landen) refers to the historical region de Nederlanden: those principalities located on and near the mostly low-lying land around the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta.

[48] Fleming is also the name used for immigrants from the Low Countries, most of them from Flanders, who came to Scotland over a 600 year period, between the eleventh and seventeenth centuries.

Norwegian flaum ‘flood’, English dialectal fleam ‘millstream; trench or gully in a meadow that drains it’), with a suffix -ðr- attached.

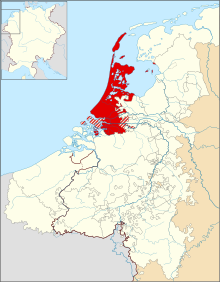

Holland has, particularly for outsiders, long become a pars pro toto name for the whole nation, similar to the use of Russia for the (former) Soviet Union, or England for the United Kingdom.

Today the two provinces making up Holland, including the cities of Amsterdam, The Hague and Rotterdam, remain politically, economically and demographically dominant – 37% of the Dutch population live there.

[62] Although the government initially refused to change the text except for the Estonian, recent Dutch passports feature the translation proposed by the First Chamber members.

Calques derived from Holland to refer to the Dutch language in other languages: Toponyms: As the Low Country's prime duchy, with the only and oldest scientific centre (the University of Leuven), Brabant has served as a pars pro toto for the whole of the Low Countries, for example in the writings of Desiderius Erasmus in the early 16th century.

In 1566, Philip II of Spain, heir of Charles V, sent an army of Spanish mercenaries to suppress political upheavals to the Seventeen Provinces.

A number of southern provinces (Hainaut, Artois, Walloon Flanders, Namur, Luxembourg and Limburg) united in the Union of Arras (1579), and begun negotiations for a peace treaty with Spain.

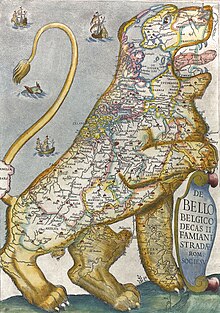

This was from the start of the Dutch Revolt against Spain on maps heroically visualised as the Leo Belgicus[64] or personified as the maiden Belgica or Belgia.